Honnavar, Karnataka: First, in 2011, the sea took away some of their land. Three years later, the waves demolished a section of their home. That is when Budhwant Karvi, 40, knew it was time to move but his elderly parents refused.

Budhwant Karvi, 40, visits the remains of his old home in Pavinarkurve village in Honnavar, Karnataka, on festivals and special occasions. To stop the erosion, the government constructed a stone wall, but it wasn’t enough to hold back the waves.

“They said we have lived here for generations and will continue to do so,” said Karvi, a worker on a fishing trawler that sails the Arabian sea.

Karvi’s home is in Pavinakurve, a village along the scenic Honnavar coast with blue waters reflecting the sky in Western Karnataka. The view from the home was once a narrow strip of sandy beach and the vast Arabian sea. On the right is the island of Basavaraj Durga, a popular tourist destination.

The view from Pavinakurve and the island of Basavaraj Durga in northwestern Karnataka. The sandy beaches of Pavinarkurve are being steadily eroded.

Seven years ago, the waves began to crash against the walls of Karvi’s home made of red, large bricks. “At times the waves would completely wash over our home and leave behind plastic bottles that were discarded in the sea by people,” Karvi said, pointing to the waste bottles on the land. Soon the sandy strip of the beach went under water. Then one by one the sea swallowed six guntas (1/7th of an acre) of the land the family owned, roughly six times the size of an average two-bedroom flat.

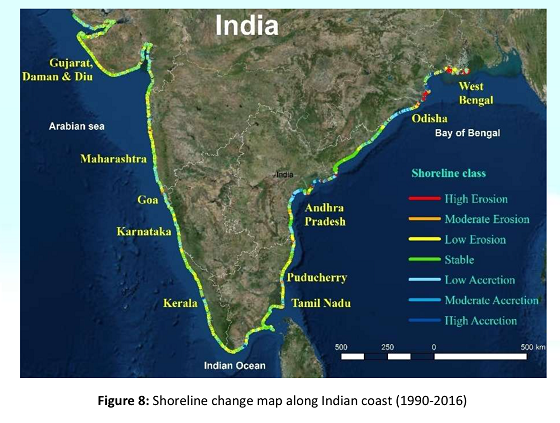

Millions living on India’s coasts are threatened as India has lost 33% of its coastline to erosion in 26 years between 1990 and 2006, according to a report released in July 2018 by the National Centre for Coastal Research (NCCR) in Chennai, which is mapping changes to India’s shoreline, and is affiliated to the Ministry of Earth Sciences.

This is the second story in our series on how climate change is disrupting people’s lives (you can read the first part here). The series combines ground reporting from India’s climate change hotspots with the latest scientific research.

India has a coastline of 7,500 km–nearly three-and-a-half times the distance between Ahmedabad and Kolkata–divided almost equally on the east and the west of the country. Along it are nine states, two union territories (UT) and two island territories. Of the country’s 1.28 billion people, 560 million, or 43%, live within these coastal territories.

Of the coastline that is eroding, 40% is in four states/UTs alone. West Bengal has lost 99 sq km of land in the past 26 years, making up 63% of the state’s coastline and equivalent to the area occupied by 18,500 football fields. Puducherry has lost 57% of its coastline, Kerala 45%, and Tamil Nadu 41%, to heavy erosion.

India’s coasts are under attack both from man-made activities–such as growing construction, damming of rivers, sand mining and destruction of mangroves–as well as natural causes linked to climate change such as rising sea levels, according to the report.

Growing construction, rising temperature, threatens coastline

India has 5,264 large dams and another 437 dams are currently under construction, according to the Central Water Commission (CWC). Of these, the highest–2,354–are in Maharashtra, followed by Madhya Pradesh (906) and Gujarat (632). These dams starve the coasts of sediments that the rivers would otherwise carry, disturbing the natural equilibrium.

Then, there are 13 major ports, 46 fishing harbour and 187 minor ports on the coast for the building and maintenance of which sediments are regularly removed. This sediment is rarely ever returned to the coast.

All this has left India’s coasts vulnerable to the full impact of climate change. “Climate change is making weather systems in the Bay of Bengal erratic,” said M.V. Ramana Murthy, director of NCCR. “We have some evidence for sea level rise. The Lakshadweep lagoons, which are enclosed water bodies, are also getting eroded because of sea level rise.”

Global warming will cause the sea levels to rise well beyond the year 2100. This rise could be as much as the height of a 500 ml bottle of coke to the height of four such bottles put together if global warming raises temperatures by 1.5 degree Celsius. If the Earth warms beyond this, the rise in sea level could be even more, according to the latest report by United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released in October this year.

Rising sea levels are predicted to disproportionately affect fishermen like Karvi and farmers owning fields along the coast.

In the past two years, Karvi’s entire home was ravaged by the sea. Even as his parents refused to move, Karvi and his siblings moved away with their families in tow. They now live in rented homes.

With the little money they had, they constructed a two-room mud home with no windows and a roof so low that one has to bend to enter, where their parents lived till their death in 2017.

Soon after, the waves began to cross the stone wall built by the government and gnaw at the remains of their old home, now reduced to rubble. The Karvis return to the old house, now reduced to debris, on special occasions. There is a tulsi plant outside that Karvi returned to on the day of Dussehra to offer prayers. In Honnavar, the only asset those like Karvi have, are their homes and their land. With the sea swallowing up both, Karvi and his siblings have nothing left.

In Pavinakurve village, many high yielding paddy fields along the coast are no longer suitable for agriculture as crops don’t grow in soil contaminated with the salty sea water.

The waves are only expected to rise higher as climate change causes changes in wind speeds. In the next three decades, coastal erosion will occur 1.5 times faster than the past three decades, according to a 2016 joint study by researchers of the Indian Institute of Technology in Mumbai and the National Centre for Earth Sciences Studies in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala.

Walls to fight waves

Many countries, including India, have responded to this challenge by building hard engineering structures such as walls or bunds along the coastline. These are just a short-term solution, said Prasanna Patgar, regional director for environment for Karwar district, that also oversees Honnavar. They also might redirect the waves and cause another area along the coast to erode. Worse, as the sand below them shifts, the walls sink.

At the moment, state governments are spending hundreds of crores of taxpayers’ money to construct walls which get eroded in a few years. But, why?

“People want immediate solution and building a wall is one,” Patgar explained. As waves erode wealth accumulated over a lifetime, people panic and administrators are pressured to offer a quick fix.

Other alternatives that work, such as mangroves, are either too expensive or time consuming.

Natural barriers are most effective against coastal erosion. They take years to establish themselves and become effective.

Mangroves go a long way to reduce wind speeds and the swell of waves during storm surges. They bind the sand together and arrest erosion. “There is also the thermodynamic shelterbelt model in which four levels of vegetation are planted,” Patgar explained. “Grass is planted closer towards the sea, followed by shrubs, herbs and finally the trees. But these plants take 5-10 years to establish and become effective.”

Another option that has worked on a 40 km stretch off the Puducherry coast is a structure based on the erosion patterns and requirements of the particular stretch. “We brought back the sediment naturally by building a submerged structure that mimics how coral reefs protect an island,” Murthy explained. Carrying out a scientific study for the 40 km stretch and coming up with the best design for the structure cost Rs 50 lakh.

To do that along India’s 7,500 km coastline would be too expensive. Even if the money was found, there aren’t as many experts as would be needed to study the entire coastline.

A coastline in distress

Coastal erosion hotspots are spread all along India’s coastline. There are several hotspots along the Kerala coastline, recently left devastated by floods, according to a 2015 study. Areas nearly 2 km inland were found to be eroded. The Tamil Nadu coast is also impacted by erosion, but the eastern coast, around the Bay of Bengal, is the worst affected.

Low and moderate erosion spots along India’s coastline.

Source: National Assessment of Shoreline Changes along Indian Coast; July 2018.

Apart from increasing sea levels, climate change is also going to change weather patterns along the coast. “The intensity and the number of tropical storms, called cyclones, in India are likely to increase in coastal areas,” said Gerd Masselink, professor of Coastal Geomorphology at the University of Plymouth, in the United Kingdom. “The effect will depend on where you are on the globe. Some areas might become less stormy and other areas might become more stormy.”

“There can be changes in the wave direction as the climate changes. This might change the longshore sediment transport, which is movement of sand along the beach,” Masselink added.

Some coastal areas are likely to flood more and global warming will cause the water temperatures to rise. All these changes will have a direct impact on the production of fish and consequently those, like Karvi, who depend on it for a living.

TH Nayak’s extended family owned land on the Pavinakurve island (in background), which has now been eroded by the Arabian sea in northwestern Karnataka.

Standing at the edge of Karki village in Honnavar, TH Nayak, 74, points to the expanse of the Arabian sea. “We had relatives living on the stretch of land there. Now it is all under water,” said the former Karnataka bureaucrat. His home was nearly 5 km away from the sea. Between the sea and his home shielded by Pavinakurve was an estuary. “It was so shallow that we could walk across it,” he said. In the last few decades, the entire topography of the area has changed.

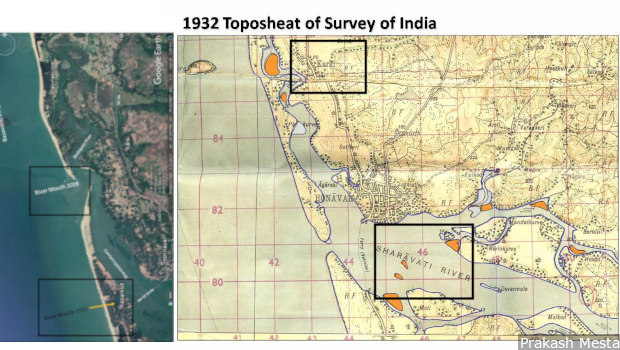

Image on the left is from Google Earth and on the right is a 1932 map from the Survey of India.

Left: The mouth of the Sharavathi river has moved over 4 km from Kasarkod (south) to opposite Karki village (north). Right: A 1932 map of the same region that shows the position of the mouth of the Sharavati river. The island of Pavinkurve is a longer stretch of land and Karki village merely had a stream in front of it, instead of the Arabian sea.

Karki village now overlooks the mouth of the Sharavathi river which merges into the Arabian sea. When Nayak was growing up, the mouth of the river was several kilometres away near the neighbouring Kasarkod village.

“Coastal erosion is a natural process but the rate at which the erosion is happening here has accelerated over the past few decades,” explained marine biologist Prakash Mesta, of the Centre for Ecological Sciences in Kumta, who is currently working on a project on coastal ecology and global warming.

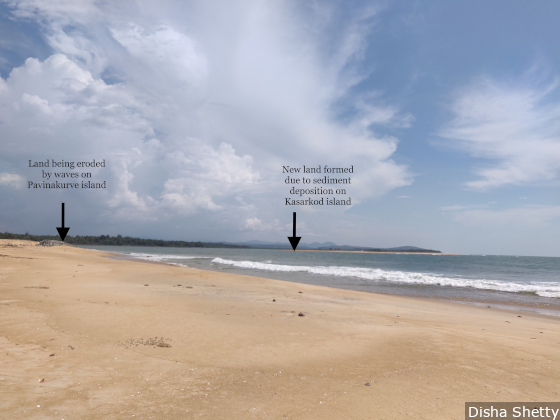

While land from one side of the river mouth is going under water, new land is emerging on the other side. This process is called accretion.

Nearly 29% of India’s overall coastline is accreting, according to the NCCR report. Odisha (51%) and Andhra Pradesh (42%) have seen a maximum increase in their coastline.

While the island of Pavinakurve (on the left) is losing land to erosion, new land is being formed on the island of Kasarkod (right) due to deposition of sediments called accretion. The new land goes to the government and not the ones who lost their land to erosion.

While Karvi and Nayak are losing their land due to erosion and not being compensated for it, the new land the sea throws up goes to the government.

“Climate change along the coast has affected the livelihoods of the fishermen community. The new land can go to them to make up for the land they have lost,” said Ramachandra Bhatta, former professor of Fisheries Economics at the College of Fisheries in Mangalore. “If the government does a risk assessment study and offers them an insurance cover, the fishermen will not need to go begging to the authorities after every disaster, the frequency of which will only increase going forward,” said Bhatta, explaining that the government has yet to conduct such a risk assessment.

Human activities worsen natural erosion

For over two decades, Aurofilio Schiavina, co-founder of Pondicherry Citizen’s Action Network (PondyCAN), has been watching the beaches of Pondicherry disappear due to erosion. While he agrees climate change is a factor, he highlights the need to check man-made structures like building coastal walls, dams, as well as illegal activities like sand mining.

At Honnavar, for instance, locals revealed a kilogram of sand sells for Rs 5 and the sand mafia routinely take away truckloads of sand from the beach.

Schiavina also agreed with the decision recalling the proposal to build a wall from Chennai to Kanyakumari right after the tsunami struck in 2004. “The damage that would have done in ten years would be more than what climate change would have done in decades,” Schiavina said. “We need policies rooted in science,” he added.

New rules on coastal regulation unscientific

Avoiding construction close to the coast is one of the easiest steps to take, according to scientists. The technical knowledge to identify areas that are at risk of erosion is available.

“People think erosion is always bad thing, but erosion at one location causes sedimentation somewhere else,” Masselink said. “A heavily managed coastline, for example a beach with a seawall, cannot adapt very well to climate change impacts and requires constant attention, whereas a natural coastline, or one that is managed using more sustainable methods on management such as nourishment, can naturally adapt to climate change impacts.”

Any sand taken away from the coast needs to be replaced, added Murthy. “We need at least 100 metres of space along the coast.”

The government, though, has other plans. In April this year, a new coastal regulatory zone draft was released in which the No Development Zone (NDZ) around coastal areas was reduced from 100 mt to 50 mt allowing for more construction along the coast in rural areas–the opposite of what scientists advise. Coasts in urban areas don’t have NDZ at all. The move is being hailed as one meant to benefit builders.

And what’s our defence against climate change? “There is no way other than being vigilant,” said Murthy.

(Disha Shetty is a Columbia Journalism School-IndiaSpend reporting fellow covering climate change.)