Between 2001 and 2013, state lawmakers unfairly awarded rural road building contracts worth Rs 3,592 crore ($540 million) to contractors from their own caste, a new study by Princeton University, USA, published in the Journal of Development Economics, has shown.

Legislators colluded to unfairly award rural road building contracts worth Rs 3,592 crore, a new study suggests. When MLAs and district collectors shared a surname, a contractor with the same surname was more likely to be awarded a contract. These roads were 7-12% more expensive to construct and in 497 instances, were possibly not constructed at all.

The contracts amounted to 4% of the total spending on the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana (PMGSY). Unfairly awarded contracts often resulted in more expensive road construction, the study found. Hundreds of these roads appear to have never been built, based on the 2011 census records, keeping hundreds of thousands of people cut off from road access.

Princeton researchers evaluated data from 88,020 rural roads projects awarded just before and after closely contested state elections, to contractors having the same surname as the sitting member of legislative assembly (MLA). In close elections, the winning and losing candidates are presumed to have similar characteristics. If MLAs are intervening in the award of contracts, a shift toward contractors with the same surname would be evident, and no equivalent shift for the unsuccessful contender.

The use of a surname or last name as a measure of proximity between MLAs and contractors was based on the presumption that being caste- or religion-specific and following the paternal line, the last name is “a good predictor of connections between individuals from the same area (state, district or constituency) or linguistic region, which both the contractor and MLA are likely to be,” Jacob N. Shapiro, co-author of the study and professor at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University, told IndiaSpend.

Connection does not necessarily denote a familial connection but a common background or network that increases a contractor’s comfort level in approaching an MLA when bidding for a contract, and the likelihood of the MLA being receptive.

If the MLAs had not influenced the allotments, the researchers would expect to see around 2,200 roads allocated to contractors with the same name as the MLA, based on a model they created. In fact, there were 4,127–roughly 1,900 too many. Essentially, the share of contractors whose name matched that of the winning politician in close elections increased from 4% before the election to 7% after, showing the power of the MLA to intervene in the allocation of roads in their constituency, despite having no official role to play in the PMGSY.

The researchers excluded elections where the winning and losing MLA had the same names, and elections in Tamil Nadu, where surnames are not commonly used.

That favouritism exists in the allotment of the PMGSY projects has been reported earlier. In 2013, of 113 mega road construction projects awarded by the Vijay Bahuguna government in Uttarakhand, 75 contracts were reported to have been awarded to well-connected people on a single-bid basis. One of the awardees was reported to be the brother-in-law of state rural development minister Pritam Singh.

MLAs with the surnames Kumar, Lal, Patel, Ram, Reddy, Singh and Yadav were most likely to have indulged in corrupt practices, Shapiro’s study says.

IndiaSpend spoke to a PMGSY contractor with one such surname who did not wish to be identified. When asked if the local MLA has to be bribed to get a PMGSY project, he said, “We bribe the MLA, but everyone in the system, including the local journalist who observes what it going on, expects a share and gets it.”

When IndiaSpend asked a representative of the rural development ministry about Shapiro’s findings, they refuted the allegations of collusion, saying, “A system exists for roads constructed under the PMGSY to be inspected by national- and state-level quality monitors.”

How corruption prevents uptake of essential services, increases inequality

Before PMGSY was launched in 2000, 40% of India’s 825,000 villages lacked a road providing all-weather access to markets, jobs and public services such as healthcare and education. The programme aimed to plug this gap for villages with more than 1,000 people by the year 2003, and for habitations of more than 500 people by 2007, eventually reaching 178,184 habitations in all.

By December 2017, 130,974 habitations had been connected under PMGSY and another 14,620 had been connected through state government programmes, so that 82% of the total eligible habitations had been connected.

Shapiro said this has been a significant initiative with huge growth benefits, but there is clearly some undue influence on the programme which means the benefits are not as large as they could have been.

Roads built by politically connected contractors were roughly 10% more expensive to construct, or, worse, possibly not constructed at all, denying a large number of people access to a road, the report found.

Across the sample, they found that 497 all-weather roads listed as completed and paid for in the PMGSY monitoring data were missing in the 2011 census all-weather roads data suggesting that these roads were never built. These missing roads kept 857,000 people at least partially cut-off from the wider Indian economy.

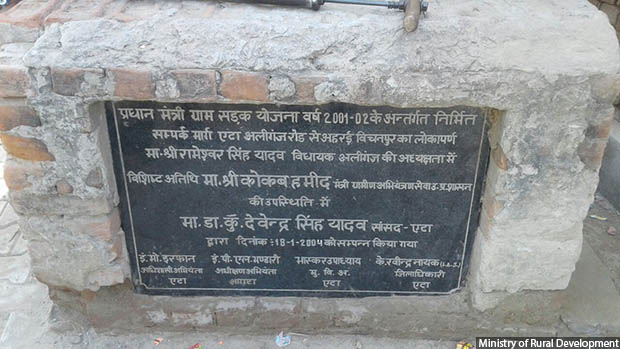

“There is no question of a missing road,” a source in the ministry of rural development said, in response to IndiaSpend’s question about the findings of the study. However, the ministry requested a few examples of missing roads. Co-researcher Jacob Shapiro provided IndiaSpend with three examples, which were shared with the ministry. In response, the ministry shared this photograph as proof of construction of one of the missing roads. This project completion marking stone states January 18, 2004 as the date of completion of the road whereas the entry for this road in the study data set states December 22, 2005 as the date of completion. The ministry did not provide any photos to support the construction of the other two examples, despite IndiaSpend’s request.

A 2016 performance audit by the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India for the period from April 2010 to March 2015 drew a similar conclusion. In the CAG’s sample of 4,417 works costing Rs 7,735 crore–12% of the Rs 63,878 crore spent during the period–19 states had shown unconnected habitations as connected, while excluding eligible habitations from road projects; nine states had built roads to connect habitations that were already connected; and seven states had shown 73 road works as completed though they did not provide complete connectivity to targeted areas.

The preferential allotment did not favour small firms or first-time contractors, Shapiro’s research found, which is not unexpected.

“When a good network becomes the qualifier for getting a road construction contract, the chances of an unconnected contractor from a less privileged family tapping this business opportunity are lower,” Rama Nath Jha, executive director of Transparency International India, which monitors corruption and transparency, told IndiaSpend. “This is one more example of how corruption perpetuates poverty and inequality.”

Corruption in India is largely opportunistic, and spurred by greed, not vote-buying

Shapiro and his co-researchers concluded that the corruption they saw in PMGSY was opportunistic. Contrary to the common perception that politicians who win elections favour business persons who funded their campaigns, the study found no clear evidence of vote buying.

Instead, they found that corruption arose within kinship networks because these provided the trust needed to engage in risky collusive behaviour. “Members of a family or caste network are likely seen as trustworthy, the least risky collaborators,” Shapiro explained.

“We have observed that people who indulge in corruption work in tandem, they create a good network among themselves,” Jha of Transparency International India agreed.

In a December 2017 survey by Transparency International India, 45% of the 34,696 respondents across 11 states said they had paid a bribe at least once in the past year. “People paid up because they had good reason to believe that without doing so their work would be delayed or never done,” said Jha. “And they feared or did not want to take the trouble to blow the whistle.”

“On the other hand, corrupt public employees are driven by greed, they are willing to take and enjoy what is not rightfully theirs,” said Jha. “The absence of a deterrent goes in their favour.”

Anti-corruption laws have not deterred malpractice because of delays of up to 25 years in award of punishment for corruption-related offences and diluted sentences, he said.

Break bureaucrat-politician nexus, monitor closely, make politicians accountable

The first step for ending corruption is to acknowledge it exists.

“There is no question of a missing road,” the ministry of rural development source said, “Sometimes, a small portion of a road may not have been constructed due to land acquisition issues or forest department issues.” They said the ministry is conducting geospatial mapping of all roads, which will show their exact alignment and verify their existence.

In 2017, a parliamentary panel had reported gross anomalies in implementation of rural road projects and asked for the creation of a national database of corrupt contractors to be blacklisted from bidding.

As big an issue is figuring out how to deter politicians from such corrupt practices. For this, it is important to understand how the MLAs pulled off preferential allotments when they had no official role in the programme.

Compared to other public works programmes, PMGSY is designed to limit the scope for corruption. Funded by the central government, it is managed by local implementation units, which are controlled by State Rural Roads Development Agencies. However, the central government monitors the programme.

In finding that road contracts were more likely to be preferentially influenced when the highest ranking bureaucrat in the district, the district collector, shared the MLA’s surname, the study provides evidence for the role of district collectors as intermediaries for corruption. “From a policy perspective, these findings indicate that more could be done to insulate the officials implementing government programmes at the local level, including those involved in PMGSY,” the study suggested.

Interestingly, the study found less corruption–defined by missing roads and inflated construction costs–in districts where the district collectors were in their 13th and 16th years of service. These are milestone years when IAS officers’ performance is scrutinised for promotion.

Also, while the preferentially allocated roads were between 7% and 12% more expensive to construct than fairly awarded roads, the cost inflation was lower before elections. The researchers explained this on higher pre-election scrutiny and the greater cost to a politician of getting caught.

Therefore, more stringent monitoring would help constrain corrupt practices. In fact, Shapiro said the continuing involvement of the central government is why his study found evidence of corruption in limited aspects of the programme.

Another deterrent may be to formally involve MLAs in the PMGSY and other local projects where they are likely to have a say.

IndiaSpend asked the PMGSY contractor why he approached the MLA when MLAs have no official role in the tendering process. “MLAs understand the local conditions, they help ensure that we get the road projects and that we can design these as needed for the carriage expected to run on the roads. They also ensure we get paid for implementation,” he said.

If the general experience is that the MLAs play a role in implementing a project, albeit informally, it may make more sense to actually make them responsible and therefore locally accountable.

“If voters held their MLAs responsible for the services delivered under PMGSY, the latter would have an incentive to limit corruption,” said Shapiro. “By contrast, a scheme in which local politicians have no formal role but over which they still retain influence through informal channels is an ideal opportunity to engage in corrupt practices.”

(Bahri is a freelance writer and editor based in Mount Abu, Rajasthan.)

Courtesy: India Spend