Dissents are not rare but powerful ones are. Justice Fazl Ali’s dissent in AK Gopalan vs. State of Madras stating that the ‘procedure established by law’ in Article 21 is due process and not any law passed by the government, differing from the majority view, is the prevailing position of law today but then, it was a lone dissent in a newly Independent India facing not just a core constitutional problem but the authoritarian moves by the state.[1] This is just an anecdotal example to highlight how important dissenting judgements are, especially for future generations to bank upon.

The last decade has seen the Supreme Court deliver one landmark judgement after another, like the ones in cases of Supreme Court AOR Association vs. Union of India(NJAC Judgement), Navtej Singh Johar vs. Union of India (Decriminalising parts of Section 377), Justice KS Puttaswamy vs. Union of India (Privacy as a fundamental right and upholding Aadhar), Indian Young Lawyers Association vs. State of Kerala(the Sabarimala Case), Shayara Bano vs Union of India(Declaring Instant Triple Talaq Unconstitutional) etc.[2]

In all these cases, except in the case of Navtej Singh Johar, each had a strong dissenting opinion. And those dissenting verdicts form a considerable part of academic discourse today-whether it be Justice Indu Malhotra’s dissent in the Sabarimala Case or dissent in the Puttaswamy’s case by Justice Chandrachud (now CJI).

In the light of recent discussions on the collegium system of the appointment of judges and the government vocal-near aggressive stance on this system, it is important to revisit the dissent by Justice Chelameswar in the case of the proposed NJAC to understand the legal perspective that supports the NJAC act and the related constitutional amendment.

The legal regime under the NJAC

There are two parts to the NJAC legal regime. One is the Constitutional amendment to allow for the NJAC to be the recommending entity for the appointment of judges, instead of the CJI led collegium.[3] And the second part is the NJAC Act which details out the procedures to be followed by the NJAC.[4]

The constitutional amendment removed the provision which mandated that the appointment of judges be made in consultation with the judges of the Supreme Court and added that the appointment be based on the recommendations of the NJAC.[5] The amendment also inserted three more articles:

124A-constituting the NJAC including 4 ex officio members i.e. CJI, two other senior most judges of the Supreme Court, Law Minister and two eminent person of which one should be SC ST, OBC or Women. The two eminent members be nominated by the committee consisting of Prime Minister (PM), Leader of Opposition (LOP) and the Chief Justice of India (CJI). The act or proceedings of the National Judicial Appointments Commission shall not be questioned or be invalidated merely on the ground of the existence of any vacancy or defect in the constitution of the Commission;

124B-Declaring the duties of the NJAC as recommending names for appointment of judges of the Supreme Court and the High Courts and the transfer of the judges from one HC to another and ensure that the person recommended is of ability and integrity;

124C-Giving Parliament the power to regulate the procedure for the appointment of Chief Justice of India and other Judges of the Supreme Court and Chief Justices and other Judges of High Courts and empower the Commission to lay down by regulations the procedure for the discharge of its functions, the manner of selection of persons for appointment and such other matters as may be considered necessary by it. Other amendments were made removing the provisions where consultation with the judiciary was required and replaced the Judiciary’s positions with the NJAC.

Effectively, the appointments and transfers in constitutional courts, which used to happen exclusively in consultation with the judiciary, would happen on recommendation of the NJAC after the amendment. However, the Supreme Court in a 4:1 majority verdict[6] struck down the 99th Constitutional Amendment.[7] The second part of the NJAC regime is the NJAC act. NJAC Act lays down the procedure for the appointment of the judges and states that the NJAC shall not pass a recommendation if any two members object to the name.[8] This again is not specifically stated for transfer and the act stated that the commission would specify regulations for the purpose of transfer.

To summarise the essence of the NJAC regime, Parliament amended the constitution to empower itself to make regulations on appointment of judges to constitutional courts. It formulated a commission which would recommend the appointment of judges to the president. To make it balanced, and not only controlled by the executive, the commission would consist of three members from the apex court, one member from the government- law minister, and two other ‘eminent members’ – who would be nominated by a high-powered committee with the prime minister (PM), leader of the opposition (LOP) and chief justice of India (CJI) as members. The committee also had a check on its functioning: if two members oppose a recommendation, the recommendation shall not or cannot be passed. Finally, the recommendation of the NJAC shall or cannot be questioned just because there is a vacancy or a defect in the constitution of the commission.

The challenge was, in effect, that this act and the amendment violated the basic structure of the constitution by breaching the principle of the judiciary being separate from any executive influence or interference.

Dissent of Justice Chelameswar

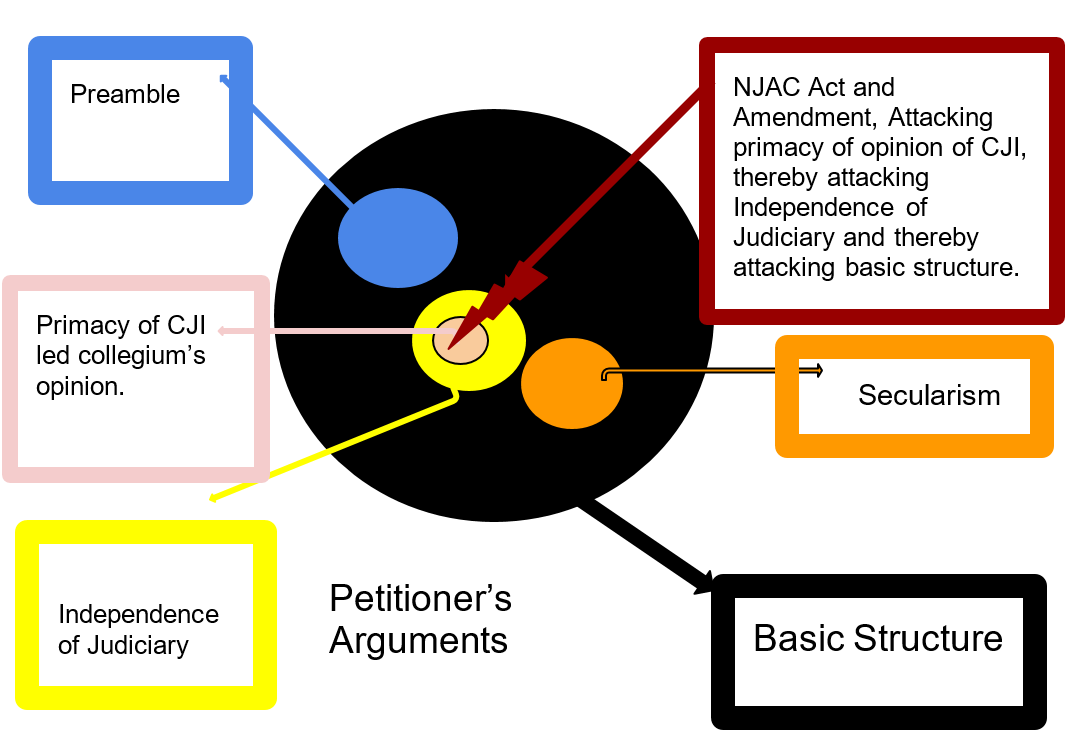

Simply put, the petitioners’ arguments were that independence of Judiciary is a basic feature of the Indian Constitution and the primacy of the CJI’s opinion i.e., Collegium opinion is an essential element of such a feature: according the judgements of SC that are now famously known as Second and Third Judges cases. These cases can be said to have created the collegium system. More about these cases can be read here. The amendment which dilutes the primacy of the CJI led collegium’s opinion, according to the petitioners, violated the essential element of the basic feature, thereby violating the basic structure of the constitution. And violation of basic structure of the Constitution was declared to be unconstitutional in the Keshavananda Bharati vs. Union of India, 1973.

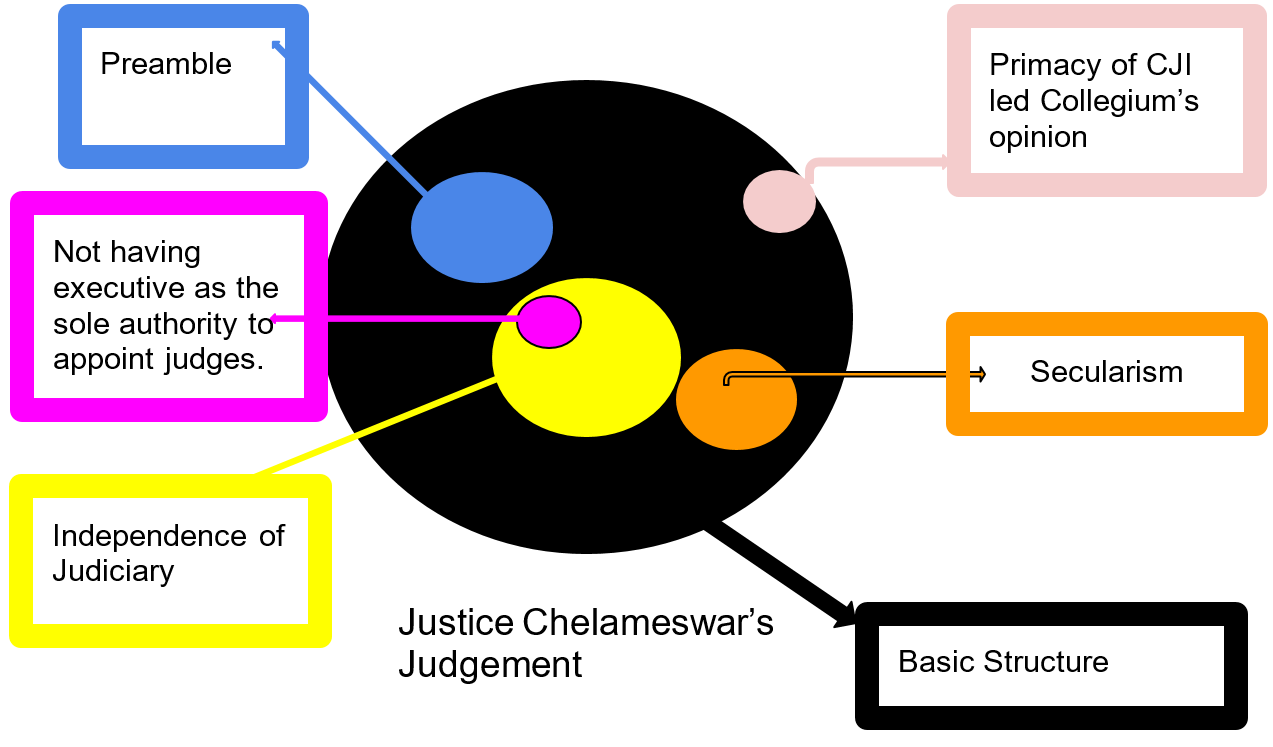

Justice Chelameswar’s dissent (the Dissent) revolves around two primary questions he chose to answer. One question is whether the mechanism within the Constitution instituted by the Constituent Assembly i.e., Article 124 prior to the amendment is the only way to secure the independence of the judiciary or not. The second one flows from a probable answer to the first poser i.e., if there are alternatives, does the NJAC amendment transgress boundaries of constituent power.

The dissent relies on Dr. BR Ambedkar’s opposition to the various models on appointing judges to arrive at a conclusion that neither Parliament nor the Executive are to be given the sole power to decide the judges’ appointment, the first for political reasons and second for the obvious reason; the Executive is literally party to far too many disputes before the courts. It also relies on the fact that the Constituent Assembly rejected the idea of the appointment power being totally vested with the judiciary. [9]

Para 66 of the Dissent stated “The system of Collegium the product of an interpretative gloss on the text of Articles 124 and 217 undertaken in the Second and Third Judges case may or may not be the best to establish and nurture an independent and efficient judiciary. There are seriously competing views expressed by eminent people, both on the jurisprudential soundness of the judgments and the manner in which the Collegium system operated in the last two decades.”

The Dissent also discusses the question whether Parliament can come up with a different procedure for the appointment of judges, replacing what has already been decided by the Supreme Court in the second and Third judges’ case.

The Dissent also differentiated between the basic features and basic structure of the Constitution and holding that the primacy of the opinion of the CJI does not form the basic feature of the Constitution, negating the petitioner’s arguments that it does. And consequently, the Dissent states that the amendment, therefore, does not affect a basic feature, further negating the petitioner’s arguments.[10] The Dissent instead states that the basic feature is actually “non- investiture of absolute power in the President (Executive) to choose and appoint judges of CONSTITUTIONAL COURTS.” And then it concludes that this basic feature is not abrogated by the amendment. Since primacy of the Collegium’s opinion is not a basic feature, the amendment does not violate the basic structure, the Dissent concluded.

And with respect to two points, one about government pushing their candidate for appointment and the second one about the inclusion of eminent people, interfering with the Judiciary the Dissent engaged in them, but in a way that is unclear. The Dissent simply states that since the executive is only represented by the law minister i.e., ⅙ (one-sixth) of the entire committee, the Judiciary if it wants to stop a recommendation, it can do so with its own members. There is a provision that if two judicial members object to a recommendation, it would not pass. Moreover, the Dissent also states that the presence of the executive – which has so much an excess of power in the area of defence, fiscal policies, protection of life and liberty – will have much to contribute and to exclude them is a trait that is absent in democracies. The dissent, as stated before, relies on constituent assembly discussions saying that the framers did not put their exclusive trust in either the CJI just like they did not put exclusive trust in the executive.

The unclear part (in Justice Chelmeswar’s dissent) is that no justification has been given as to how the inclusion of executive – which also happens to be a party to the multiple disputes that go on before the courts, does not result in a clear problem of conflict of interest. While it emphasises on what the presence of the executive brings to the table, the same data and expertise could be brought to the notice of the appointing commission without the executive being explicitly present within it.

An issue in plain sight that was left unengaged with in the Dissent was the polyvocal nature of the Supreme Court- especially the collegium – and the supposedly more heterogeneous nature of the executive. Though it was not explicitly so framed by the petitioners at all, the Dissent explicitly states that as long as two judicial members unite and do not agree to a recommendation, the government cannot push a candidate forward. If this situation were to be imagined indeed, then there are multiple scenarios that could have the government push its candidate. Given the polyvocal nature of the Court (i.e., the trait where multiple senior judges of the apex court do not have the same opinion about a recommendation), if the three judges within the NJAC are not on the same page, which is not just normal, but frequent, the executive could get their way.

Another point raised by the petitioners that the Dissent negates is this – the petitioners’ argument that the placement of two eminent personalities could be misused since there is a clear possibility that both the parties i.e. The PM and LOP could group up and nominate their own people as the ‘eminent personalities’ and that this could totally shift the balance of power in NJAC. The Dissent stated that “possibility of abuse of power conferred by the Constitution is no ground for denying the authority to confer such power.”[11] However, the tenure of an eminent member in the proposed NJAC is three years and if this collusion happens once, the eminent member will hold immense power to influence the decisions of the commission. The dissent does not deal with this possibility at all.

A new and important point the Dissent brings out is how Transparency is a vital feature in constitutional governance and rationality- which must govern every sphere of state action. This is in response to how collegium proceedings are opaque etc. However, it does not clarify as to how presence to two eminent members who are handpicked by a high powered committee are the harbingers of much needed transparency, and how intense such transparency would be, for the interference of some external member to be so justified.

Conclusion

The above understanding is not to undermine the reasoning that was given in the Dissent or to outright-ly support the collegium system as it exists. The points about transparency raised in the Dissent are pertinent and different measures of transparency would have to be included for the collegium system to be more according to the ideals of the constitution.

However, it is submitted that, with respect that the Dissent, while providing a powerful opposition to the continuance of collegium system, has not adequately clarified how the proposed NJAC model is constitutionally sound.

[1] AIR 1950 SC 27

[3] The Constitution (Ninety Ninth Amendment) act, 2014

[4]THE NATIONAL JUDICIAL APPOINTMENTS COMMISSION ACT, 2014 ACT NO. 40 OF 2014

[5] Section 3, The Constitution (Ninety Ninth Amendment) act, 2014

[6] October 6, 2015, Supreme Court struck down the constitutional amendment and the NJAC Act restoring the two-decade old collegium system of judges appointing judges in higher judiciary

[7] AIR 2015 SC 545

[8] Section 5(2) and Section 6(6) of the NJAC Act, 2014.

[9] Supra Note 6, at 525 Para 65,

[10] Supra Note 6, at 561, Para 99

[11] Supra Note 6, at 579, Para 107

Related:

Collegium System is Law of the Land, Must Be Followed: Supreme Court to Centre

Collegium system & transparency of judicial appointments: a conundrun

Is the Centre overreaching itself in returning Collegium recommendations, again?

Six Members in the Supreme Court Collegium until May 13, 2023