We’ve long become accustomed to the notion that reading allows us to connect with others and find support during times of crisis. In a recent Guardian interview, #MeToo founder Tarana Burke recalled how, as a child, she turned to literature as a survivor of sexual assault:

One of the original plates illustrating the novel Pamela, by Samuel Richardson. Etched by L. Truchy and A. Benoist after paintings by J. Highmore – Houghton Library

I read a lot when I was young. Those were the things that helped change the trajectory of my life. And the first glimpses of healing, and understanding what had been happening to me as a child, came from the literature that I read.

If Burke had been reading 18th-century English literature, she would have discovered some remarkable examples, in fiction and non-fiction sources, of writers willing to break the cultural silence on harassed and abused women, particularly working women.

In 18th-century Britain, working women mostly laboured as domestic servants, a profession that muddied the boundaries between the professional and the personal. Women servants lived with their employers and were often beset by sexual pressure on all sides – from their male masters to their servant peers. They were frequently raped. Some concealed their resulting pregnancies and gave birth alone in their garret rooms (outcomes for the babies were poor, which often resulted in charges of infanticide). And yet their stories circulated via the era’s new ways of writing.

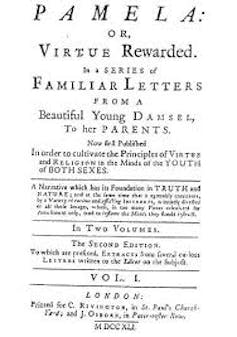

Pamela, Or Virtue Rewarded was first published in 1740. Wikimedia Commons via Olaf Simons and Ottava Rima

Instances of sexual assaults against female servants were detailed in the 1700s via innovative fiction and nonfiction prose. One of the century’s leading novelists (sometimes considered a founder of the form) was Samuel Richardson, and his 1740 bestseller, Pamela, Or Virtue Rewarded, gives us a copybook story of relentless workplace harassment.

The 15-year-old Pamela repeatedly fends off her employer. His frequent groping, attempts at rape, and kidnapping recall many of the modern day abuses documented by #MeToo. Pamela is slow to see the full extent of Mr B’s nefarious intentions: how could a man so charming, intelligent and impressive subject her to such suffering? Pamela evades the worst of her master’s plans and successfully reforms him into her husband.

Richardson’s novel may not square with modern ideas of romance, but, in its time, it told an astonishing story of how a working teenager could protect herself against a man who held every form of power (age, money, class, masculinity) over her.

Eliza Haywood

Richardson was the not the first novelist to defend women against male sexual transgression. In 1725, the popular writer Eliza Haywood published Fantomina, Or Love in a Maze, a short novel in which the heroine is sexually coerced by a promiscuous rake. Fantomina transforms her rake into a constant lover by taking on four different disguises (including that of a servant), her lover none the wiser.

Frontispiece to The Female Spectator, London: 1746. Harvard University

In the concluding pages of her 1743 self-help guide for female servants Haywood shared strategies for evading male come ons, including those from masters (both married and unmarried), masters’ sons, and gentleman lodgers. She advocated modesty at all times – but also encouraged servants to speak about their rights to virtue (taking a page from Pamela) and to seek a new position if necessary. Haywood cautions especially about avoiding men “in liquor” and against the master’s son, explaining how to spot his false flattery and promises. Follow these strategies, Haywood assures her servant audience, as you, too, deserve “valuable and happy” lives.

Forced ‘seduction’

If #MeToo has brought today’s hidden stories to light, the past reminds us that just as women have always worked, they have always been harassed in the workplace. In my research into labouring women in Georgian Britain, I’ve encountered hundreds of grim tales of “seduction” (a frequent code word for coercion or assault).

Some of the most heartbreaking stories were documented by printed trials from the Old Bailey starting in 1674. By 1729, trial accounts grew longer and more narrative in response to the public’s appetite for true tales of suffering. They were one of the few print outlets in which women servants could speak for themselves (albeit through the courts).

Despite the innovative spotlight that these new forms of narrative shone on the struggles of working women, new forms of media in Georgian Britain laid the groundwork for many of the fissures that continue to haunt feminist movements today. “Deserving” women (especially those who dressed modestly) were more likely to merit attention. Stories overwhelmingly focused on white women at a time when Britain was vastly expanding its role in the global slave trade.

There was no Time’s Up movement to establish a legal fund for those abused domestic servants – but these stories managed to draw attention to the plight of working women. In 1739, Thomas Coram established the Foundling Hospital for the children of impoverished mothers, even illegitimate ones.

Neither the Foundling Hospital nor other Georgian charities were enough to protect the countless women who suffered abuse in the workplace, but the literary marketplace created new print platforms for these women to be seen and heard. Rather than being spoken for by a third-party author, today’s new media has importantly enabled women to share their own stories via Twitter, Facebook and live courtroom testimony. Perhaps it will support those who have not yet dared to speak or have been left out of the conversation for all too long.

Chloe Wigston Smith, Lecturer in 18th-century Literature, University of York

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.