It has happened to me, and it can happen to anyone.

In plain sight of my unsuspecting family, I was radicalised during my teenage years. It did not matter that I lived a privileged life — not all terrorists fit the stereotype of poor, illiterate people who have nothing to lose.

The events changed my life, and would have ended it were it not for divine intervention. What I realised was that anyone can be systemically brainwashed to the point of committing violence.

How did it happen? How does someone growing up with a silver spoon connect with an ideology of anger and hate?

13-year-old me in 1997-98, during a visit to my house (under construction at the time) in Lahore.

Where it all begins

In the late 1990s, my family moved back to Lahore from Saudi Arabia. I was enrolled at an elite boarding school, where I would meet our 9th grade Islamic Studies teacher, a stocky man with a flowing orange beard, always dressed in a spotless white shalwar kameez and a black waistcoat.

He claimed to have fought against the Soviets in the 80s. He regaled us with stories from his time as a Mujahideen fighter in Afghanistan. His lectures had little to do with our syllabus, and included colourful, emotional sermons on the devilry of Hindus, Christians and Jews, as well as Sufis, Shias, Ahmadis, and whoever he considered to be heretics, polytheists and kafirs.

For him, fighting the enemies of Islam was our divinely ordained duty. If we did not strike the heretics down wherever we found them, we were no better than men who ‘wear mehendi on their feet and bangles on our wrists’, that is, we were no better than women.

He termed this blanket call for violence in the name of honour as ‘jihad’.

For 13-year-old me, this message was inspiring. I was also insulted by his labels — I was not at all womanly, and I certainly did not own any bangles.

He instigated my sense of honour, and this was enough to spur me into action.

It took only a month for me to go up to him and ask how I could further the cause of jihad. He suggested donating money. If I could spare 10 rupees for Allah, I could buy a bullet that would tear through a kafir’s chest in Kashmir.

I started giving him whatever meagre sum I could, before spending the rest of my pocket money at the canteen. Rs50, Rs10, Rs5 — he had promised me I would receive a portion of the bullet’s 'sawab' .

Then, I wanted to learn more. My teacher offered me books if I was willing to pay for them. I could not read Urdu well, so I delved into the English translation of the Holy Quran and the Sahih Bukhari (a collection of hadith).

But balancing daily reading school work wasn’t enough for a teenager infatuated by the idea of martyrdom. Eventually, I found myself before my teacher, expressing my decision to go fight the infidels in Kashmir.

He did not respond immediately and put me off for another few weeks. I went to him several times until he agreed.

The plan was this: on the last day of school, I would leave for the training camp in AJK. I was to bring Rs700 and meet my teacher at his house. We would then go to the bus station at Minar-i-Pakistan, where I would be joined by a travelling partner.

Once I reached the camp, I was to write a letter to my parents informing them of my decision, and of my desire to embrace martyrdom in the way of jihad.

Divine intervention

As fate would have it, my grandmother fell gravely ill the night before I was to leave. It was perhaps the last day before the Eid break, or the winter break, and I reached my hostel room to see my family already there, waiting for me.

My belongings were packed and ready and we immediately left for the hospital. My grandmother had contracted an incurable strain of Hepatitis C from a routine injection at the hospital, and survived the next few months in extreme pain. Greatly distracted by her illness, my parents decided I would commute to school from home for the rest of the school year.

I began living at home.

The tragedy wreaked havoc on my mother's emotional state, and it became a difficult time for my family. In such a state of sadness and loss, I could not leave them. In any case I had little time to myself on campus to consider meeting my teacher.

Somehow, someway, I kept putting off my trip to his house.

By the time my summer vacations ended, I had shelved my plans of leaving for jihad completely.

Finding my way to jihad

The spirit of what I knew then to be ‘jihad’ stayed with me and still shapes my life to this day.

There was an empowering sense of purity and certainty in my connection to the source of absolute truth. I felt mercy and forgiveness radiating from the Quran and the hadith, especially when I read them in a language I could understand.

Most of all, I felt fulfilled: I was aware of the Creator in the smallest details and happenings of life.

But there was much that I now know to be gravely misguided. I was made to feel disdain against those who chose ‘inferior’ beliefs; I dehumanised those I wanted to fight, and I belittled the act of taking a life to the point where it seemed like nothing at all — like brushing away a troublesome insect.

When I realised that I had once walked a dangerous path, filled with both darkness and light, I tried to read and learn as much as I could to answer my questions and seek out the truth. I must report that every answer has led me to even more questions, and I have learned just enough to know that I know nothing.

I have come to see Islam as a vast ocean of knowledge, an expanse of philosophy, wisdom and truth, and in my sinful life so far I have just barely scratched the surface.

I cannot claim to be any kind of expert, but as a seeker and a student, it is evident to me that the extreme reduction of Islam to a list of do’s and dont’s is a great corruption of our religion. Perhaps it is the real cause behind how Muslims are now split into so many hostile divisions with mutual hatred and enmity.

In the years since my failed attempt at joining a training camp, I have felt the call of what I now believe is the real jihad.

I have worked in multiple careers; financial services, telecom, advertising, publishing, and even as a part-time debate coach at my alma mater. But each time, even after settling into a career, I have left the path in front of me to begin a new one. I have been restless, unable to find satisfaction or peace in worldly pursuits.

After December 16, 2014, my heart once against felt this long-forgotten call to jihad. This time the pull was irresistible. I could not go back to the way things were, and relieved myself from corporate responsibilities completely.

I decided instead to focus full-time on a new mission: addressing the problem of religious extremism in our society.

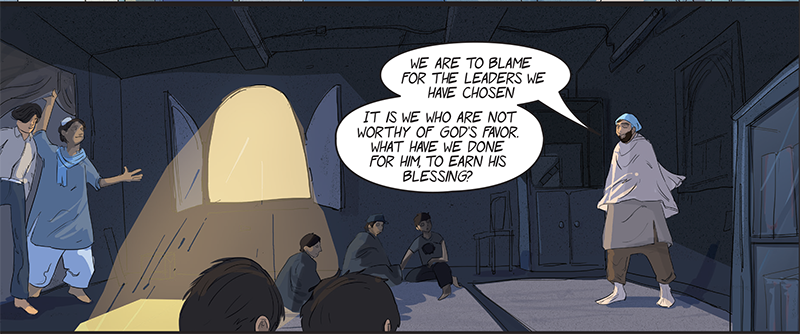

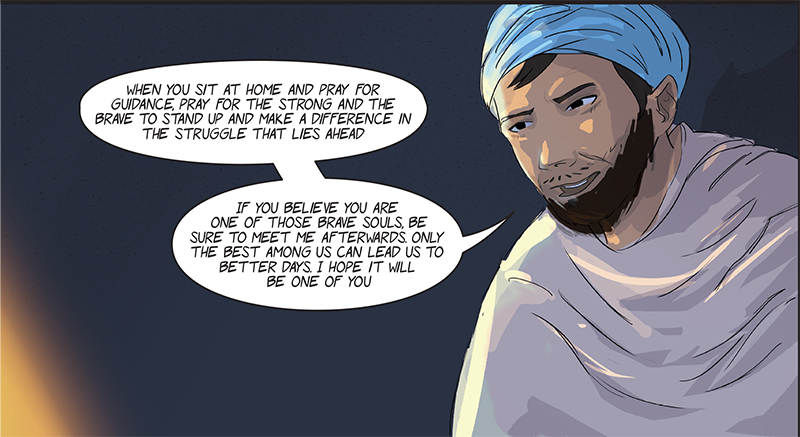

Now, I write stories and comic books for schoolchildren. My series highlight the issue of religious extremism, in the hope of getting children to reject the toxic hatred society exposes us to.

I do this because I hold myself partly responsible for all the innocent men, women and children who have lost their lives in terrorist attacks.

I do this because I am indebted to those who have sacrificed themselves to protect us, and because I wish to be of service to the unnamed millions who continue to be misled into a false, hateful form of religion rather than the pure and everlasting truth of Islam.

For those of you who have made it this far in this very long post, I hope you have felt a calling as well. If you do feel the call, first learn, then do as you see fit to the best of your ability and position.

This is a dangerous time for those who dare to speak the truth, so if you can take action or speak out, you too must play your part.

I do this because I cannot stand by while another 16-year-old is brainwashed into thinking he will go to heaven for killing a 12-year-old, is then labeled a ‘terrorist’ to be shot by his own kind, or blown up by a drone fired by a foreign country.

I do this because tomorrow, if God forbid one of your children or loved one is harmed, I don’t want to look in the mirror and realise that I could have done something, said something to stop it.

This article was first published in Dawn.com and is being re-published with permission