The Delhi High Court in May 2022 delivered a split verdict in the case of RIT Foundation vs. Union of India in which the constitutionality of the Marital Rape Exception (MRE) under Section 375 and Section 376B of the Indian Penal Code was challenged.[1] This article seeks to critically examine and understand in depth, the judgements of Hon’ble Justices Ravi Shankar and Rajiv Shakdher who delivered separate and contrary opinions that resulted in the split verdict.

While Justice Rajiv Shakdher struck down the MRE, Justice C. Hari Shankar dismissed the petitions—upholding the constitutional validity of the MRE. This article will focus on Justice C. Hari Shankar’s opinion that upheld the constitutionality of the provisions, essentially denying any woman recourse under law prosecuting rape within the institution of marriage.

Facts

- The RIT Foundation, along with the All-India Democratic Women’s Association (AIDWA) and two other individuals, filed a petition challenging the marital rape exception (MRE) under Section 375, Exception 2 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) 1860. The petition argued that the MRE should be struck down as it violated the constitutional rights of women and perpetuated gendered violence and discrimination.

Provisions involved

The following provisions were challenged:

- Section 375, Exception 2 of the IPC: This exception stated that sexual intercourse by a man with his own wife, who is not under 18 years of age, was not considered rape.

- Section 376B of the IPC: This section dealt with the punishment (2 years) for rape committed by a husband who was separated from his wife.

- Section 198B of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC): This sections states that no court shall take cognisance of an offence punishable under section 376B of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) where the persons are in a marital relationship, except upon prima facie satisfaction of the facts which constitute the offence upon a complaint having been filed or made by the wife against the husband.

These abovementioned provisions remain in the same form in the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 with different section numbers via Sections 63 and 67 of the BNS and Section 221 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023.

Arguments advanced against MRE:

- The MRE violated the constitutional goals of autonomy, dignity, and gender equality enshrined in Articles 15, 19(1) (a), and 21 of the Constitution.

- The MRE treats women as the property of their husbands after marriage, denying them sexual autonomy, bodily integrity, and human dignity as guaranteed by Article 21.

- The MRE violated the reasonable classification test of Article 14 as it created a distinction between married and unmarried women, denying equal rights to both.

- The MRE should be struck down, and the punishment under Section 376B should also be invalidated as it discriminated between offences committed by separated husbands, actual husbands, and strangers.

Arguments for MRE’s constitutionality:

- The crux of these arguments was twofold—court’s lack of power to read down the MRE thus creating a new offence and the fact that legislature had made a conscious decision to not label non-consensual sexual act between husband and wife as rape to protect the institution of marriage, by extension, families and progeny thus there is a legitimate object that the state is seeking to achieve via the MRE.

Justice C. Hari Shankar began his judgment by outlining the context and the specific challenge before the court. The petitioners argued that Exception 2 to Section 375, which states that sexual intercourse or sexual acts by a man with his own wife, the wife not being under eighteen years of age, is not rape, is unconstitutional. They contended that this exception violates Articles 14, 19(1)(a), and 21 of the Constitution, which guarantee equality before the law, freedom of speech and expression, and protection of life and personal liberty, respectively. The petitioners emphasized the importance of sexual autonomy and consent, arguing that the exception undermines these principles by immunizing husbands from prosecution for non-consensual sexual acts within marriage.

On original objective and the continuing legislative intent

Justice C. Hari Shankar addressed the original objective and the continuing legislative intent behind the Marital Rape Exception (MRE) in his judgment. He emphasised that the original objective of the MRE, as conceived in the 1860 IPC, was not based on the outdated “Hale dictum,” which suggested that marriage implied a wife’s consent to sexual intercourse with her husband. Instead, the MRE was rooted in the unique nature of the marital relationship and the need to balance individual rights with the preservation of the institution of marriage.

He stated:

“There is nothing to indicate that the ‘marital exception to rape,’ contained in the Exception to Section 375 of the IPC, or even in the proposed Exception in Clause 359 of the draft Penal Code, was predicated on the ‘Hale dictum,’ which refers to the following 1736 articulation, by Sir Matthew Hale: ‘The husband cannot be guilty of rape committed by himself upon his lawful wife, for by their mutual matrimonial consent and contract the wife hath given herself up in this kind unto her husband, which she cannot retract.’ Repeated allusion was made, by learned Counsel for the petitioners, to the Hale dictum. There can be no manner of doubt that this dictum is anachronistic in the extreme, and cannot sustain constitutional, or even legal, scrutiny, given the evolution of thought with the passage of time since the day it was rendered. To my mind, however, this aspect is completely irrelevant, as the Hale dictum does not appear to have been the raison d’être either of Section 359 of the draft Penal Code or Section 375 of the IPC.” [Para 13]

Justice C. Hari Shankar further explained that the continuing legislative intent behind retaining the MRE is to preserve the institution of marriage. He highlighted that the legislature, in its wisdom, has chosen to treat non-consensual sexual acts within marriage differently from those outside of marriage. He argued that this distinction is based on an intelligible differentia that has a rational nexus to the object of preserving the marital institution.

In essence, Justice C. Hari Shankar maintained that the continuing legislative intent behind the MRE is to protect the institution of marriage by distinguishing between non-consensual sexual acts within marriage and those outside of it. He emphasized that this distinction is not arbitrary but is based on a rational assessment of the unique dynamics of the marital relationship and the broader societal interests at stake.

On rational nexus and intelligible differentia

Justice C. Hari Shankar further analyses the concept of “intelligible differentia” and “rational nexus” in the context of Article 14 of the Constitution.

His interpretation rests on the foundational premise that the marital relationship is intrinsically distinct from all other forms of relationships, particularly in that it carries an inexorable incident of a legitimate expectation of sexual relations.

He articulates this position as follows:

“The primary distinction, which distinguishes the relationship of wife and husband, from all other relationships of woman and man, is the carrying, with the relationship, as one of its inexorable incidents, of a legitimate expectation of sex.”

This formulation forms the central pillar of his justification for treating non-consensual sexual acts within marriage differently from those outside of it. The judgment thus constructs an argument wherein marriage, as a legal institution, grants a presumption of consensual intimacy, differentiating it from other relationships where consent must be independently established.

He states:

“The legislature is free, therefore, even while defining offences, to recognise ‘degrees of evil.’ A classification based on the degree of evil, which may otherwise be expressed as the extent of culpability, would also, therefore, be valid. It is only a classification which is made without any reasonable basis which should be regarded as invalid. While the Court may examine whether the basis of classification is reasonable, once it is found to be so, the right of the legislature to classify has to be respected. Where there is no discernible basis for classification, however, or where the basis, though discernible, is unreasonable or otherwise unconstitutional, the provision would perish.” [Para 144]

Internal inconsistencies within the IPC framework

However, this reasoning, while maintaining internal consistency within the judge’s interpretative framework, encounters contradictions within the broader legal architecture of the IPC—particularly when juxtaposed with Section 376B, which criminalizes non-consensual intercourse between a husband and wife during separation.

Section 376B, which prescribes a lesser punishment (up to two years of imprisonment), nonetheless acknowledges that marital status alone does not create an absolute or irrevocable expectation of sexual relations. This provision, therefore, implicitly recognizes a wife’s autonomy and the necessity of consent, at least in specific contexts. The logical inconsistency emerges in two key aspects:

1. Recognition of autonomy in judicial and non-judicial separations

- Section 376B (punishment for rape by a husband during separation) does not require a court-ordered decree of separation for its application, meaning that a wife living separately from her husband—without a state-recognized order—still retains legal protection against non-consensual intercourse involving her own husband.

- This directly contradicts the fundamental assumption of the MRE, which presumes that marriage inherently entails continuous consent to sexual relations. If the institution of marriage is so distinct and special, then why does the law acknowledge that consent is required during separation, even without formal judicial recognition? It is to ensure that all institutions are within the bounds of the Constitution and the value system it espouses. To this extent, the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1983 added the current 376B (it was added as 376A but was later renumbered to 376B in 2013 after the Criminal Law Amendment, 2013).

2. The status of underage marital rape under IPC

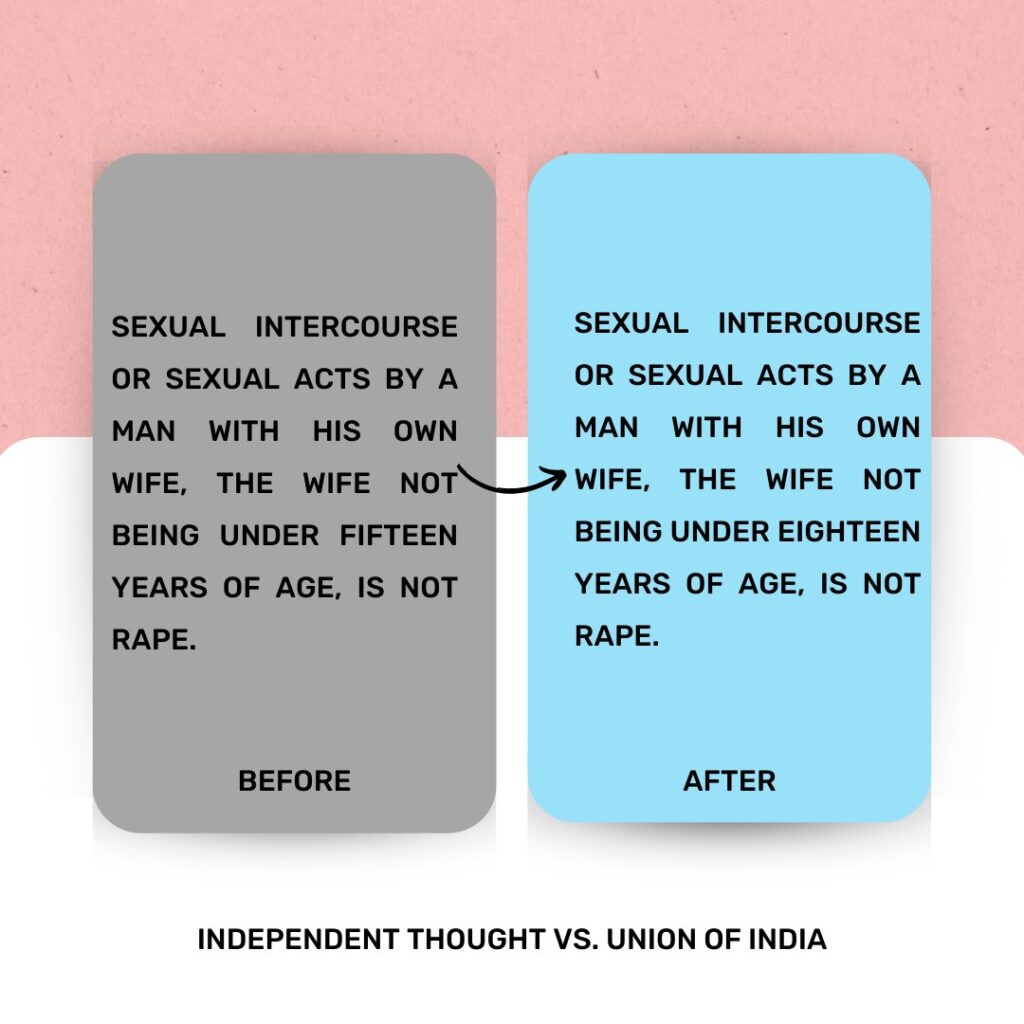

- The inconsistency is further compounded by the fact that the IPC (via the Independent Thought vs Union of India judgement) criminalizes non-consensual intercourse with a wife below the age of 18, thereby recognizing the primacy of consent in certain marital contexts.

- If the marital bond inherently carries an expectation of sexual relations, as the judgment asserts, then the legal system’s refusal to extend this principle to child marriages undermines the assumption of an absolute and uninterrupted sexual expectation within marriage. However, it has been extended to bring it in consonance with the constitutional principles in Independent Thought vs. Union of India.[2]

The judgment by Justice C. Hari Shankar relies on the intelligible differentia test to uphold the MRE, but the incoherence in its application becomes evident when viewed through the lens of Section 376B and related provisions. If marriage is a uniquely protected institution, then its sanctity should logically override even non-judicial separations—yet it does not. This suggests that when the law is compelled to acknowledge a wife’s individual autonomy, it does so in ways that directly conflict with the underlying justification for the MRE.

One could argue that a clear distinction exists in the punishments, as spousal rape during separation carries a lighter sentence (two years) compared to the harsher penalties under Section 375. However, this distinction collapses under scrutiny because:

- The recognition of consent during separation (including non-judicial separation) means that the “legitimate expectation of sex” argument is not absolute.

- The law, therefore, implicitly concedes that the marital institution does not override a wife’s right to autonomy in every instance.

- If the expectation of sexual relations within marriage were as absolute as the judgment suggests, then non-consensual intercourse during a non-court-ordered separation should not have been an offense at all.

The IPC’s contradictions — recognizing marital consent in separations (Section 376B) and criminalising underage marital rape — dismantle the “intelligible differentia” justifying the marital rape exception (MRE). By acknowledging that consent matters even within marriage, the law inadvertently concedes that marital status alone cannot negate autonomy. This fractures the MRE’s foundational logic: if a separated or underage wife retains constitutional rights to bodily integrity (Articles 14, 21), why does cohabitation erase them? The disparity in punishments (2 years vs. 10 for non-marital rape) further portrays a patriarchal hierarchy, implying a husband’s “claim” outweighs a wife’s dignity — a stance antithetical to Article 15’s prohibition of gender discrimination and to Constitutional Morality as espoused in Navtej Singh Johar vs Union of India.[3]

On Article 19 and 21

Justice C. Hari Shankar also addresses the argument that the exception violates Article 19(1)(a) by restricting a married woman’s right to sexual self-expression. He rejects this contention, stating that the exception does not compromise a woman’s right to consent or refuse consent to sexual relations. Instead, it merely recognises the complex interplay of rights and obligations within a marital relationship. Similarly, he dismisses the claim that the exception infringes upon Article 21, asserting that there is no fundamental right under the Constitution for a woman to prosecute her husband for rape in the context of marriage. It is here that Justice C. Hari Shankar makes deeply problematic observations that highlight and symbolise the underrepresentation of women and their voices, both in the society and in the judiciary that has contributed to emergence views such as follows.

He states as follows:

“If one were to apply, practically, what has been said by Mr. Rao of the crime of “rape”, the entire raison d’etre of the impugned Exception becomes apparent. As Mr. Rao correctly states, rape inflicts, on the woman, a “deep sense of some deathless shame”, and results in deep psychological, physical and emotional trauma, degrading the very soul of the victim. When one examines these aspects, in the backdrop of sexual assault by a stranger, vis-à-vis nonconsensual sex between husband and wife, the distinction in the two situations becomes starkly apparent. A woman who is waylaid by a stranger, and suffers sexual assault – even if it were to fall short of actual rape – sustains much more physical, emotional and psychological trauma than a wife who has, on one, or even more than one, occasion, to have sex with her husband despite her unwillingness. It would be grossly unrealistic, in my considered opinion, to treat these two situations as even remotely proximate. Acts which, when committed by strangers, result in far greater damage and trauma, cannot reasonably be regarded as having the same effect, when committed by one’s spouse, especially in the case of a subsisting and surviving marriage. The gross effects, on the physical and emotional psyche of a woman who is forced into non-consensual sex, against her will, by a stranger, cannot be said to visit a wife placed in the same situation vis-à-vis her husband. In any event, the distinction between the two situations is apparent. If, therefore, the legislature does not choose to attach, to the latter situation, the appellation of ‘rape’, which would apply in the former, the distinction is founded on an intelligible differentia, and does not call for judicial censure.” [Para 184]

Essentially, Justice C. Hari Shankar says that rape by a stranger is more psychologically damaging than rape by a husband of his wife.

For starters, this line of reasoning differentiates the intensity of suffering on the basis of the identity of the victim’s vis-a-vis her relation to the accused depending on whether the accused is the victim’s husband or a stranger. This exercise was unnecessary, if not deeply flawed and regressive.

Moreover, the same Section 376 which punishes rape has a stricter punishment for aggravated rape—which punishes rape by people in authority or relatives. Therefore, the law deems rape by people who are in positions of authority/trust more serious than other cases. This distinction should have prompted Justice C. Hari Shankar to delve into the issue with much more sensitivity to the suffering of a victim which it failed to do.

This is not to say that the relation between people in authority and the victims is same as marital relationship. The reason for quoting this example is to show that trauma cannot be said to be less or limited when a husband commits rape when compared to a when a stranger commits the offence.

Secondly, a simple search would have given Justice Hari Shanker studies and scholarly research that discussed how traumatic it is for women to be raped by their own husbands. From Diana Russell’s pioneering work on Rape in Marriage in the 1980s to recent studies on marital rape that reveal its devastating physical, reproductive, sexual, and psychological impact on women well into old age, there is well-established scholarship on the effects of marital rape. Given this, Justice C. Hari Shankar’s casual categorization of these traumas into different tiers is deeply concerning if not problematic (Bhat and Ullman, 2014; Band-Winterstein T. and Avieli, 2022)[4][5]

On creation of a new offence

Justice C. Hari Shankar further considers the potential consequences of striking down the exception. He notes that doing so would create a new offence of “marital rape” and would necessitate a re-evaluation of the punishments prescribed under Section 376 of the IPC. He also highlights the practical difficulties that would arise in proving consent in cases of marital rape, given the private nature of the marital bedroom. The judge argues that these considerations weigh in favour of retaining the exception, as the legislature has the authority to make policy decisions regarding criminal law.

He maintained that the MRE is an integral part of Section 375 of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) and that removing it would fundamentally alter the scope of the offense of rape. He argued that the MRE is not merely an exception but a critical component of the legal framework that defines the offense of rape.

He stated:

“Offences may legitimately be made perpetrator-specific or victim-specific. In the present case, Section 375, read as a whole, makes the act of ‘rape’ perpetrator-specific, by excepting, from its scope, sexual acts by a husband with his wife… The specification of the identity of the man, and his relationship vis-à-vis the woman, which presently finds place in the impugned Exception might, therefore, just as well have been part of the main provision.” [Para 203]

However, MRE itself is what makes the offense of rape perpetrator-specific, and removing it would merely restore the general applicability of the offence to all individuals, regardless of their marital status. This view is supported by the Supreme Court’s decision in Independent Thought vs Union of India. In this case, the same provision was dealt with. The Marital Rape Exception, before the Independent Thought judgement, applied to non-consensual sexual acts with wife who is 15 years and above. Since it contrasted the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 and the overall Constitution, the provision was read down to have it applied to only acts with a wife who is 18 and above thus protecting those women who are less than 18 years of age.

This is what the court said in Independent Thought addressing the concerns over it creating a new offence:

One of the doubts raised was if this Court strikes down, partially or fully, Exception 2 to Section 375 Indian Penal Code, is the Court creating a new offence. There can be no cavil of doubt that the Courts cannot create an offence. However, there can be no manner of doubt that by partly striking down Section 375 Indian Penal Code, no new offence is being created. The offence already exists in the main part of Section 375 Indian Penal Code as well as in Section 3 and 5 of POCSO. What has been done is only to read down Exception 2 to Section 375 Indian Penal Code to bring it in consonance with the Constitution and POCSO.

The judgement by Justice C. Hari Shankar does not deal with this prima facie similarity between the reasoning of Independent Thought and the reasoning of petitioners as to why reading down MRE does not create a new offence. He states as follows:

But, assert learned Counsel for the petitioners, by striking down the impugned Exception, this Court would not be creating an offence. They rely, for this purpose, on Independent Thought , in which it was held that the Supreme Court was not creating an offence by reading down the impugned Exception to apply to women below the age of 18. The analogy is between chalk and cheese. The situation that presents itself before us is not even remotely comparable to that which was before the Supreme Court in Independent Thought. We are not called upon to harmonise the impugned Exception with any other provision. The petitioners contend that the impugned Exception is outright unconstitutional and deserves to be guillotined. Would we not, by doing so, be creating a new offence?

We do not see any engagement with the proposition advanced by the petitioners or with the reasoning in Independent Thought. Striking down the marital exception would not create a new offence but would merely extend the application of Section 375 to all individuals, irrespective of marital status. Justice C. Hari Shankar’s concern—that such a move would turn previously non-offenders into offenders and that criminalization is the legislature’s prerogative—remains unreasoned when examined in light of the approach taken in Independent Thought.

Conclusion

Justice C. Hari Shankar’s judgement is a mix of genuine judicial restraint and a deeply flawed reasoning that puts women and their autonomy on the back burner, for the purpose of patriarchal notions of desire in the garb of sanctity of marriage. His reasoning after a point goes from flawed to problematic when he states the following: “Any assumption that a wife, who is forced to have sex with her husband on a particular occasion when she does not want to, feels the same degree of outrage as a woman raped by a stranger, in my view, is not only unjustified, but is ex facie unrealistic.” [Para 130]

While he is entitled to present his judicial opinion, he does not provide any reasoning for differentiating the trauma of marital rape from that of rape by a stranger. We do not know if he relied on any survey, or on what basis he came to his conclusion. The assertion lacks empirical evidence or scholarly backing and instead relies solely on personal assumptions, which are disconnected from established research on marital rape trauma.

Justice C. Hari Shankar’s wisdom in exercising judicial restraint is robust, tenable and sound when it relates to the argument that such change must come from the legislature. While it might not be entirely agreeable, there is a level of doctrinal firmness to it.

However, his views on marriage, expectations of sex and autonomy of women struggle to find their ground in the concepts of constitutional morality, ethical logic but flow with the flaws of regressive outlook on what a marriage is. These flaws stem not only from an inadequate understanding of how the law attributes sanctity to marriage but also from a superficial and reductive view of the emotional and psychological trauma endured by married women when their trust is violated by their own husbands through marital rape. In this sense, the flaws not only are legal, but also moral.

The novel contribution of this judgement is not the exercise of judicial restraint but an expression of outdated perception of marriage—one that subordinates constitutional morality to patriarchal tradition.

In the next part, the judgement of Justice Rajiv Shakdher declaring the MRE to be unconstitutional and his reasoning in answering some pertinent questions raised by Justice C. Hari Shankar will be discussed.

(The author is part of the legal research team of the organisation)

[1] 2022 SCC OnLine Del 1404

[2] [2017] 10 SCC 800

[3] (2018) 10 SCC 1

[4] Bhat, M. and Ullman, S.E., 2014. Examining marital violence in India: Review and recommendations for future research and practice. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 15(1), pp.57-74.

[5] Band-Winterstein, T. and Avieli, H., 2022. The lived experience of older women who are sexually abused in the context of lifelong IPV. Violence against women, 28(2), pp.443-464.

Also Read:

Related:

A Licence to Violate: Chhattisgarh HC’s ruling on marital rape exposes a legal travesty’