The film festival going community looks down upon popular cinema, whereas the masses have (mostly) turned their thumbs down to art and parallel cinema. So, to lament that Pa Ranjith can successfully make a cinematically appealing movie but not a mass movie on caste politics is deeply troublesome.

Over the past many years, whenever a Rajinikanth movie is released, there are certain reviews which are discussed in the English media and also in the non-Tamil regions of the country. For many of them, who do not understand the complexities of the multilayered cine-politics of the South, the usual conclusion is that while the movie is a treat for Rajinikanth fans, it falls short of standards set by critics. Such reviews include celebrity critics like Rajeev Masand, Raja Sen and many more.

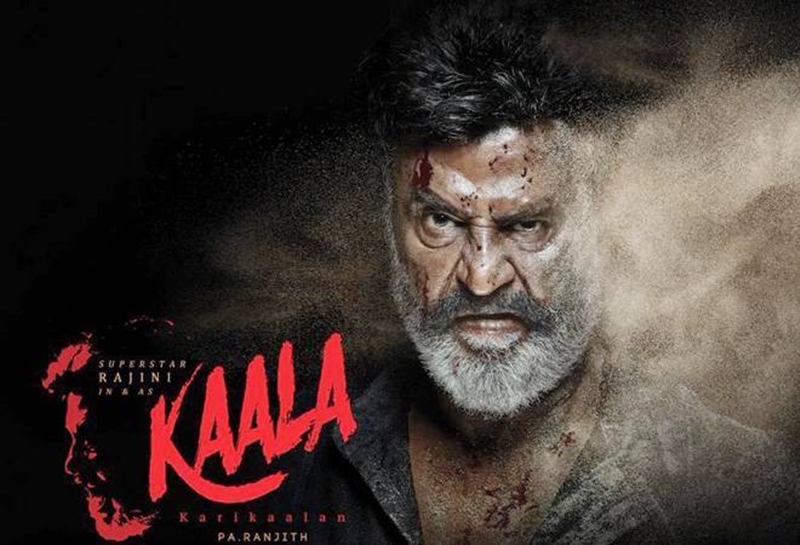

In an unexpected turn in the Tamil industry, the superstar joined hands with a young filmmaker, Pa Ranjith. Ever since their first movie Kabali was announced, the liberal intelligentsia has been in a quandary. The major problem here is not that there are multiple views on a film, or the lack of understanding of cine-politics in the South, but rather, the ‘savarna gaze’ within which these reviews are caught. Kaala also met with a similar set of reviews.

Pa Ranjith is widely known since his 2014 movie, Madras. The movie is much lauded for its realistic depiction of the Chennai slums and the symbolism used. To many critics, the film came as a treat in cinematic excellence. However, since the release of Kabali, the worry is about Rajinikanth’s stardom which the critics believe will intimidate the brilliant filmmaker in Pa Ranjith. The national award-winning film critic Baradwaj Rangan was among those who expressed this. Jayaraj, a multiple national award-winning Malayalam film director is known for the wide range of film genres he handles and for which he has received much critical acclaim. But Pa Ranjtih does not receive this applause for the switch from Madras to movies like Kabali and Kaala. There is a larger issue here.

The film festival going community looks down upon popular cinema, whereas the masses have (mostly) turned their thumbs down to art and parallel cinema. So, to lament that Pa Ranjith can successfully make a cinematically appealing movie but not a mass movie on caste politics is deeply troublesome. For instance, if Ranjith makes a movie more realistic and cinematically appealing for film lovers which still focused on caste realities, then who would the audience be? Are we saying that the masses should not watch movies which talk about such critical issues? Are such movies, then, only for discussions among academics and festival going crowds?

With just these two films, Ranjith has single-handedly shaken the collective consciousness around popular cinema not just in Tamil Nadu but across the country. In both content, and also in form. During the audio launch of Kaala, Pa Ranjith was on record saying, “I don’t dislike making a film in a cinematically appealing way. But in a society where cinema remains a mass medium for its people, making a mass film around this politics would serve the purpose of communicating the issue better.” Ranjith also confesses of the power behind Rajinikanth’s appeal and image, which again goes a great way in endorsing the issue. If this is the vision of the director, can he be spared the patronizing remarks of critics?

The biggest criticism over Pa Ranjith’s last two movies is the explicit manner in which the movies deal with caste. The question of whether caste is implicit or explicit in Kabali and Kaala can be rephrased into the question of whether caste itself is explicit or implicit in our everyday life. This question begs discussion among the ‘liberal’ understanding of caste. To this section of the population, caste exists only when an atrocity occurs. They fail to see the casteism that pervades our everyday life. They do not question the caste of the person who sat next to them in college, the food preferences they have, the caste of the people who live in the slums, etc.

Celebrity film critic Anupama Chopra’s review of Kabali revealed scant knowledge of Tamil cinema. She jokes about the suit Rajinikanth wears for most of the time in the movie. Wait! Did she get the point? She appears to have missed the entire point of the film. Among the many things the film communicated, one major aspect was the politics of clothing. Rajinikanth says in the movie, “there are many reasons why Gandhi discarded shirts and why Ambedkar wore a suit.” This was just one among the many reviews which missed the overall point of the film because of the sheer lack of context and understanding of caste.

To put it this in the simplest of terms, for someone like Gandhi, it was a revolutionary act to leave his home and shun his clothes. But for the Dalits revolution comes when they wear the best suits, live in a multi-storied building and even rise to become a don in Malaysia. With this single movie, Ranjith could subvert the entire stigma around the caste name ‘Kabali.’

Caste is all around you. Even in the air you breathe. So, the depiction of caste on a big screen can be done in many ways. It need not look like a Fandry always. So, by the implicit/explicit debate, the director has to show an atrocity or something as stark as untouchability to convince the spectators that the movie is engaging with caste. With his definite understanding of caste, Pa Ranjith does not need to do the same nor does he wish showcase just the pain of Dalits in a two-hour long art film.

As critics have also pointed out, to the majority caste is simply reflected through the gaze of class. Aren’t we naturalized in seeing only class and not caste on the silver screen? Hrithik Roshan cannot date Amisha Patel in Kaho Na Pyar Hai because he is poor. No filmmaker to this point cared enough to clearly distinct if it was only class or caste too that kept the couples apart. (Nagraj in Sairat apart) But in real life, we do understand that caste comes even before class.

Let’s be clear about where this debate emerges from. Caste has become the burden of the lower castes alone. Hence it is the responsibility of a Dalit director to educate the masses whereas a Shankar or Rajkumar Hirani does not have such a political responsibility. They are free to float in their castelessness and still tell stories about the poor and good Brahmins.

Almost all films produced in the different industries in India are filled with savarna symbols and their gods. The audience and critics do not dissect those brahminical symbols and acts as something which represents their politics. We are tamed in viewing these stories and symbols.

A vast majority would not have understood the relevance of the colours in the climax scene of Kaala. So is the case with many symbols, acts and references in Kabali. How can we criticise the director when everyone may not understand these symbols? Your social upbringing is designed so well that you understand nothing other than the privileged atmosphere around you. Are the Dalit supposed to carry the blame for your ignorance too?

As far as those critics and audience who do not understand the politics of the movie but feel that it is yet another Rajinikanth show, give yourself some more time. This is the first time you are watching something like this. Maybe another five years with the films of Pa Ranjith, Nagraj Manjule and hopefully many more, you would understand what blue or the busts of Ambedkar, Periyar and Buddha mean to the Dalits.

For instance, in the Malayalam industry, the 1980s and 90s witnessed the pouring in of Nair feudal stories. When Mohanlal acts as a Feudal lord in yet another movie, the audience went to watch the movie not because they necessarily associate with the Nair mythos of the film but to watch their star. But over many decades, these symbols have become naturalized. Every Malayali would understand what a naalukettu is even though they might not have ever seen one in their real life.

When Kaala teaser was released some felt that it is the repetition of the celebration of ‘blackness’ in Tamil cinema. But Tamil is, in fact, the only industry where a black complexioned hero can portray his role without being apologetic about his colour. Malayalam industry up to this point has remained apologetic and spends at least 10 mins of the movie to ‘humanize’ the black complexion of the hero. It is never repetitive to celebrate your ‘blackness’ in a society which considers fair complexion superior. Likewise, in the same society which considers the upper castes superior by the virtue of their birth, one has to celebrate his/her ‘Dalitness.’ Especially by the superstar himself in this case.

There is a historically rooted reason of caste reality on why this country never had any prominent Dalit director or Dalit subjectivity in films. And now that we are witnessing a new cinema experience through filmmakers like Pa Ranjith and Nagraj Manjule, the discourse on caste is entering mainstream spaces of media. These films, therefore, are being debated and reviewed through different lenses. But one finds that the mainstream film reviews are incapable of understanding the nuances of these films. It is not about whether a spectator or a critic likes the movie which talks about caste, but a caution that your reasons might be engraved in the lack of nuances in understanding caste and its various forms of discrimination.