Gulfisha Fatima was arrested on April 9, 2020, in the aftermath of the anti-CAA protests, and charged under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA). She is the only woman among the accused in the Delhi riots conspiracy case who still remains in prison. Over the years, many others have secured bail. But for Gulfisha, the legal process has become its own form of punishment – hearings delayed, adjourned or derailed altogether by procedural lapses and judicial transfers.

It has now been more than five years. She has not been convicted of any crime. And yet, her incarceration endures – not as a sentence handed down by a court, but as an unending wait, sustained by a trial that never arrives.

§

Gulfisha Fatima has now been imprisoned for over 1,900 days.

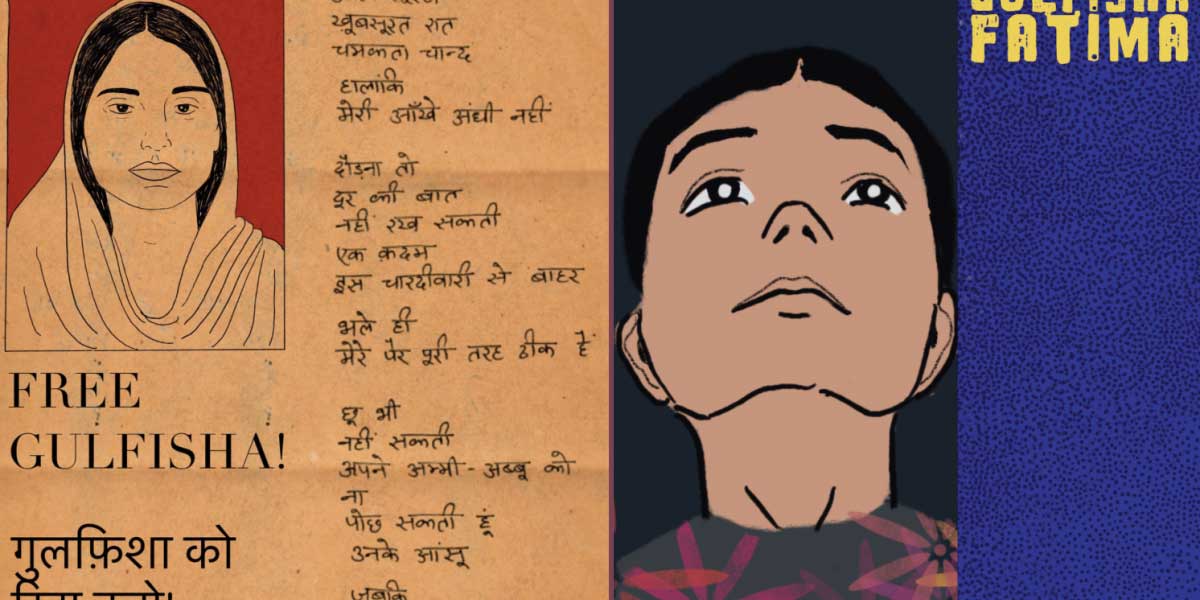

This year, on the fifth anniversary of her incarceration, a solidarity week was organised for her. Artists created posters. Writers wrote essays. We shared her story again, in public and private spaces, hoping that her name does not disappear under the weight of silence.

I mailed her a letter with the printed posters created in solidarity with her by a few artists – drawings that said ‘Free Gulfisha’. Not as a campaign or a legal demand, but a gesture of care. The kind of solidarity that says: you are not forgotten, and they haven’t succeeded in making us forget.

But the prison did not deliver the letter. The posters, it seems, were “unacceptable.” Too political, or perhaps too hopeful.

What is the state afraid of? Posters, apparently.

Between censorship and care

This wasn’t the first time something in my letters had been censored. I remember the first one I received from Gul – whole phrases had been erased with a white marker. I couldn’t make sense of what she was trying to say, or who she was referring to. Later, a friend explained that whenever the jail authorities find something objectionable, they simply blot it out with correction fluid.

What were the words being erased with whitener? Underneath those erased spaces were stories from Gul’s PadhoPadhao program – narratives about how, despite describing herself as impatient, she had become the teacher her mother always said she would be. These were letters tracing how incarceration had begun to reshape her: how she was being pushed into roles she had never imagined or wanted for herself – teaching, learning to make jewellery, sitting still for hours, enduring solitary confinement for days on end.

After that, every letter I wrote became an exercise in evading censorship. I tried to fill the pages with stories and sentences that wouldn’t be silenced. I told her about my vegetable patch, my cat, my father and my city. Each letter began to feel like those school assignments: Write a letter to your friend describing your day.

Except here, the state was assigning the prompt.

How do you write about what matters, without inviting erasure?

So I asked her questions instead, like where would you like to go on a holiday once you are out? Have you seen a beach?

She wrote back to say she’d never seen a beach. That she couldn’t imagine what it felt like to think of a ‘vacation’ much less stand at the edge of the sea, feet buried in the sand.

I started searching for photos that might convey the quiet joy of that moment – that stillness, that release. I thought of the beach photos by my friend Varun, a Chennai-based photographer who describes his work as an exploration of spaces – streets, beaches, rooftops etc. His work doesn’t draw attention to itself, and yet it stays with you – the quiet texture of everyday life, without turning people’s lives into a spectacle.

It reminded me of something Annie Ernaux gestures toward in her writing – that the everyday is never neutral (Jacobin, 2022). That to record it is not indulgent, but defiant. A way of refusing the erasure that time, power or distraction so often imposes. To linger on the mundane is also to affirm that it mattered.

And perhaps that’s why I thought of those photographs, of Gul’s life in prison, and of Annie Ernaux – because all three are preoccupied, in their own ways, with the dignity and weight of the ordinary.

I requested a copy of the photos and sent it to her; and they got delivered. After the posters didn’t make it through the jail bars, I was curious (and grateful) how the previous photos had made the cut. I realised that Varun’s photo, in its quiet ordinariness, slipped past the censors likely because it did not look political. The state missed how tenderness, too, can be a radical refusal to forget or abandon. It helped Gul escape from her immediate surroundings for a minute.

She loved the photos and wrote back saying: “I crave normal moments like these. To me, even ‘normal’ now feels like a gift.”

And in the midst of all this, somehow, our friendship grew.

We don’t come from the same city. We weren’t born into the same caste, religion or class. We didn’t go to the same universities or share any obvious markers of a shared world. We are not the same. One of us is in prison. The other is writing this from outside. And yet, in a time when it is often claimed that people from different backgrounds cannot truly understand each other, our friendship has become something rare and deeply cherished.

I remember a time, about a year and a half ago, when I was going through a rough patch. My letters to her grew infrequent, scattered, weighed down by everything I couldn’t bring myself to say. In response, Gul wrote back – gently, with concern. “Are you okay? she asked. It’s unlike you to be so quiet.”

Tucked inside her letter was a small keychain she had bought for me with her prison wages. It was her way of reaching across the bars, of being there for me in the only way she could. That letter marked a quiet turning – an unexpected tenderness. Despite everything she was enduring, it was Gul who took on the larger share of care.

And no matter how many words are blotted out, how many letters are intercepted – this is something the state cannot erase.

Silence as strategy: Censorship and carceral control in India

Writing from prison is never just a personal exercise – it is political. And it is subjected to opaque, unchecked censorship. Prison authorities are granted sweeping discretion over what detainees can send or receive, with little public accountability. While the Prisoners Act of 1894 and the Model Prison Manual of 2016 formally permit letters and reading material, these rights are routinely curtailed by vague provisions allowing officials to withhold anything deemed “objectionable” or “a threat to discipline or security”.

Rule 43.17 empowers superintendents to intercept letters “likely to endanger prison security.” But what qualifies as a threat remains undefined. There is no obligation to document decisions, no route for appeal. Letters disappear. No explanation is given. No one is notified. This is censorship by silence – absence masquerading as order.

For those charged under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), this regime of erasure becomes more insidious. Since its enactment in 1967 – and especially after amendments in 2008 and 2019 – the law has enabled prolonged detention without trial, often on speculative evidence. The 2019 amendment allows individuals – not just organisations – to be labelled “terrorists,” vastly expanding the scope of pre-emptive criminalisation.

Under Section 43D(5), bail is nearly impossible. Judges must accept prosecution claims at face value, reversing the burden of proof. Accusation becomes punishment. Professor Ujjwal Kumar Singh (2007) calls this a “detention democracy” – where the rule of law coexists with a parallel regime of suspension. Rights exist on paper but remain materially inaccessible.

This is not just the condition of those charged under UAPA – it is the logic of the prison itself. Surveillance, solitary confinement and disrupted communication are not exceptions but embedded features of carceral life. For some, especially political prisoners, these controls may be intensified. But often, the inverse is also true: ordinary undertrials, those without public attention or legal support, may experience even deeper abandonment.

What results is more than legal incarceration – it is an emotional severance. Books may get denied. Clothes for Eid from friends get denied. Letters are redacted or withheld. Care is filtered through bureaucracy.

The prison becomes a space of quiet erasure – where silence is institutionalised, and the threads of memory and connection are gradually worn thin.

What it means to remember

The refusal to deliver the letter with posters was not a surprise. Many of us who write to political prisoners have faced similar outcomes. We write, we send, we wait. Often the message arrives months later. Sometimes never. Sometimes the prisoner is told. Sometimes not. But this refusal still matters. Because it shows how deeply the state fears memory. To make a poster or to write a letter or to read her poems is to assert that solidarity is still possible – despite the fences and the years that pass.

Even when the message doesn’t arrive, it has already done its work.

When we speak of repression, we often speak of grand spectacles – raids, arrests, bans, surveillance. But power also works in small, daily gestures. The unmailed letter. The returned book. The silence from the prison gate. These small gestures are how repression is normalised.

They create a slow withdrawal not just from the prisoner, but from the political itself. Families and friends, unsure of what is safe, stop sending things that can be returned, stop writing certain words or phrases so that the letter does not go undelivered. Artists, afraid of being watched, stop drawing faces.

The prisoner does not just disappear from view – the effort is to gradually erase their side of the narrative in the public’s moral and imaginative landscape. Over time, the very idea of dissent becomes fragile, unspoken. The blank space is no longer just a person. It is a society trained to look away.

Perhaps, this is the quiet labour of solidarity: to resist forgetting. To write, to remember, to insist on presence even when presence is policed. Communication is controlled because it keeps the political identity alive.

A woman who writes, who remembers, or who is remembered – becomes dangerous. She unsettles the state’s narrative of isolation. Because the solitary prisoner is a myth; these women resist through community. Their letters become pamphlets. Their poems cross the boundaries of identity and confinement. Their art – sent or received – becomes a slogan, becomes memory. They remain in the movement even behind bars.

It is this continuity – of thought, of political belonging, of being claimed and held by others – that the state truly fears.

Anuradha Banerji is an activist and an independent researcher.

Courtesy: The Wire