On April 26, the Supreme Court dismissed a batch of petitions, with the lead petition filed by Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), seeking 100% cross verification of VVPAT paper trail slips with EVM votes, noting that EVMs are “simple, secure and user-friendly”. The Bench of Justice Sanjiv Khanna and Dipankar Datta issued concurring but separate judgements in the case of Association for Democratic Reforms vs Election Commission of India and Another (Writ Petition (Civil) No. 434 of 2023).

Responding to the plea for increasing voter verifiable paper audit trail (VVPAT) cross verification from present 5 EVMs machines (randomly chosen) in each Assembly Constituency (for both state assembly election and General Election) to 100% cross verification, Justice Khanna wrote that, “First, it will increase the time for counting and delay declaration of results. The manpower required would have to be doubled. Manual counting is prone to human errors and may lead to deliberate mischief. Manual intervention in counting can also create multiple charges of manipulation of results. Further, the data and the results do not indicate any need to increase the number of VVPAT units subjected to manual counting.”

However, significantly, the court did introduce measures to improve transparency and accountability of the present system by allowing runner up candidates positioned second and third after the highest polled candidate to seek verification and checking of burnt memory/microcontroller in 5% of EVMs per (respective) Assembly Constituency or Assembly Segment in case of Parliamentary Election.

The court recorded that such request for verification must be made within seven days of declaration of results and “The District Election Officer, in consultation with the team of engineers, shall certify the authenticity/intactness of the burnt memory/microcontroller after the verification process is conducted. The actual cost…for the said verification will be notified by the ECI, and the candidate making the said request will pay for such expenses.

The expenses will be refunded, in case the EVM is found to be tampered.” Significantly, the court refused to accede to the petitioners’ request to direct the Election Commission of India (ECI) to disclose source code of the EVM, arguing that revealing the source code can lead to its misuse.

The judgment also directed Election Commission (ECI) to ensure that Symbol Loading Units (matchbox sized apparatus used to put candidate and party information into VVPAT through laptop/PC) are sealed immediately upon use and stored in strong room(s) for 45 days after the declaration of results. Pertinently, the court remarked that feeding serial numbers and names of candidates and their party symbols in bitmap files (images) in VVPAT cannot be equated with uploading a (malicious) software, The Hindu reported.

The verdict also rejected the plea to return to ballot paper system, describing the attempt as “foible and unsound”. In addressing another technical issue regarding the design of VVPAT, Justice Khanna in his judgement noted that “ECI has been categoric that the glass window on the VVPAT has not undergone any change” and “The tinted glass used on the VVPAT printer is to maintain secrecy and prevent anyone else from viewing the VVPAT slips”, though still allowing a voter to view her printed VVPAT slip for seven seconds, confirming her candidate and party choice. The petitioners in the case were arguing that not having a full transparent view of VVPAT’s workings raises suspicion as a voter might not be sure whether a fresh slip is produced every time, or the same slip is displayed (in the case where the previous voter had cast the vote for the same), thus illicitly cutting down votes of a party and benefitting a rival party.

The order may be read here:

How do EVM, VVPAT and Symbol Loading Unit function?

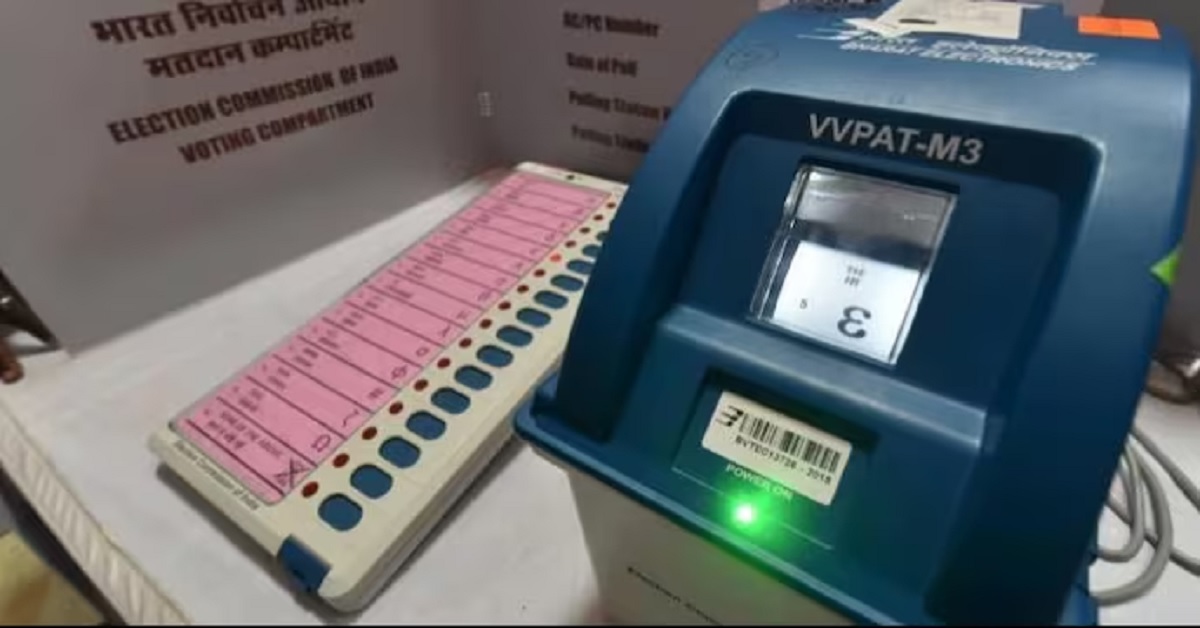

The Electronic Voting Machine or EVM unit consists of Control Unit (CU) and Ballot Unit, which jointly functions to successfully register a vote. The Control Unit is placed with the Presiding Officer or a Polling Officer and the Balloting Unit is placed inside the voting compartment, both are joined through a cable. The two units in the third generation EVMs are connected via VVPAT. The FAQ on EVM and VVPAT issued by the Election Commission notes that Polling Officer in-charge of the Control Unit will release a ballot by pressing the Ballot Button on the Control Unit and this in turn will enable the voter to cast his vote by pressing the blue button on the Balloting Unit against the candidate and symbol of his choice.

Similarly, it explains that VVPAT is an “independent system attached with the Electronic Voting Machines that allows the voters to verify that their votes are cast as intended. When a vote is cast, a slip is printed containing the serial number, name and symbol of the candidate and remains exposed through a transparent window for 7 seconds. Thereafter, this printed slip automatically gets cut and falls in the sealed drop box of the VVPAT.”

EVMs were first used in 70-Parur Assembly Constituency of Kerala in the year 1982, and since then its use was gradually increased to cover all state and national elections. VVPAT was first introduced in a bye-election from 51-Noksen (ST) Assembly Constituency of Nagaland in 2013, though its field trial had already taken place in 2011. Currently, EVMs and VVPATs are manufactured by two public sector companies, namely, Electronics Corporation of India Ltd (ECIL) and Bharat Electronics Ltd (BEL). These companies had recently refused the names and contact details of the manufacturers and suppliers of various components of EVMs and VVPATs under the RTI Act citing “commercial confidence”, Business Standard reported.

Symbol Loading Unit (SLU) is an apparatus used to transfer the details of parties and candidates for the given polling booth to VVPAT, in order to allow the latter to print the paper slip containing those details of chosen candidate and party symbol. SLUs were generally reused to feed the requisite information to numerous VVPATs across polling booths or constituencies, but with the latest court order on April 26, this will not be possible as SLUs need to be immediately sealed once they have transferred relevant data in a given constituency, and secured in a strong room, just like EVMs and VVPATs.

Challenges to the credibility of EVMs and VVPATs

While general allegations about hacking or manipulation of EVMs have been consistently raised by those who oppose EVMs on technological grounds, there has been no conclusive demonstration to prove the alleged charges, except with the possibility of physical tampering. Given that handling of EVMs is undertaken in a secured environment, with 24×7 CCTV surveillance of strong rooms, and double lock system, whose keys are held separately by two different officials appointed by the electoral officer, the possibility of large-scale rigging is difficult in the absence of physical access to the device or complicity of officials. Furthermore, EVMs cannot be connected to any wireless or Bluetooth connection given its manufacturing built.

Likewise, ECI has argued that the VVPAT has (burnt) one-time programmable memory and flash memory of 4 megabytes, which is designed to solely store and recognise a bitmap format file. It can store a maximum of 1024 bitmap files containing the symbol, the serial number and name of the candidate, and does not store or read any other software or firmware. This explanation came in response to the questions raised regarding the possibility of tempering with VVPAT machines or EVMs as connected to VVPATs through software manipulation or insertion of a malicious code.

Furthermore, first level checking (FLC) for EMVs and VVPATs are conducted in the presence of representatives of political parties to ensure that the devices are free of any flaw(s) or manipulation. This exercise is conducted well in advance of the polls (at least 120 and 180 days before the state assembly and the general election respectively), and the checked EVMs and VVPATs are then sealed with signatures of the representatives of political parties present on the said seal. For the remaining period before the election(s), the devices will continue to be placed in the strong rooms under CCTV surveillance, and only these checked devices can be used in the polls. There is also a separate checking process in before the beginning of the polls to ensure additionally level of trust and safety.

More substantial charges against EVMs are regarding the handling of EVMs rather than against EVM per se, as several instances have some to light where poll body has castigated its officials for mishandling EVMs or not following proper guidelines and SOPs. The Election Commission has also rejected the news reports which claimed that around 20 lakh EVMs were missing from ECI records, saying that reports are misleading and fake.

Incidentally, when EMVs were first piloted in 1982 in 50 out of 84 polling stations in the Parur constituency, the apex court had set aside the election result in the constituency, asking ECI to reconduct the polls using ballot papers as the law then did not permit the use of EVMs in the elections, as per the Indian Express report. As per the same report, later, in 1988, “the election law was amended to insert Section 61A, which allowed the ECI to specify the constituencies where votes would be cast and recorded by voting machines.”

Past petitions nudging for improved electronic voting system

One of the earliest petitions requesting changes in the way EMVs were used in the elections was filed by Rajendra Satyanarayan Gilda (Writ Petition (Civil) No. 406 of 2012) and Subramanian Swamy (Civil Appeal No.9093 of 2013), in which they urged the court to strengthen the electoral process by introducing paper slip trail so that the voter can verify that her vote was corrected recorded by the EVM machine. Swamy had argued that the EVMs were open to hacking, just like any other electronic device, irrespective of the claim made by the ECI to the contrary. Clubbing both the petitions, the Supreme Court bench of Justice P. Sathasivam and Ranjan Gogoi delivered its judgement on October 8, 2013, directing the Election Commission, which in 2013 had already used VVPAT in all the 21 polling stations of Noksen Assembly Constituency of Nagaland, to expand its use in phased manner throughout the country. The bench noted in its judgement that “we are satisfied that the “paper trail” is an indispensable requirement of free and fair elections. The confidence of the voters in the EVMs can be achieved only with the introduction of the ‘paper trail’”. Thus, with this order, VVPAT came to be gradually used for all state and national level elections as an essential component of the election process to assuage the doubts regarding the credibility of EVMs, and strengthen the integrity of the elections.

The order may be read here:

In 2018, a year before the General Election of 2019, petition was filed in the Bombay High Court by Manoranjan Santosh Roy, alleging serious fraud and discrepancy in the purchases and handling of EVMs. The PIL in the case claimed that the information obtained through Right to Information (RTI) from manufacturers, Law Ministry, and ECI had conflicting answers to his queries on the purchase and the handling of EVMs. Some of the news media had reported that the petition in the court had revealed that 20 lakh EVMs were missing from the custody of ECI, suggesting mishandling of the EVMs, but the said reports were rejected by the ECI as misleading.

In the same year, the petition filed by Delhi based Nyaya Bhoomi seeking replacement of EVMs with ballot papers in 2019 General Election was rejected by the bench of Justices Ranjan Gogoi, K M Joseph, and M R Shah.

In 2018 another petition was filed by M.G. Devasahayam (Writ Petition (Civil) No.1514/2018) asking the Supreme Court to increase the VVPAT paper slips verification to 50% in every Assembly Constituency. To undertake this, the petitioner asked the SC to quash the Guideline No. 16.6 of the Manual on Electronic Voting Machine and VVPAT which mandated verification of VVPAT paper slips in 1 polling booth per Assembly Constituency. ECI in its affidavit had maintained that the present ratio of verification was well above the statistically reasonable sample size of 479 EVM-VVPAT verification as suggested by the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI). It argued that the existing rule would result in verification of 4125 EVMs, way above 479 needed to achieve 99% accuracy in the election results. The petitioners in turn rejected the criteria suggested by ISI, and citing the authority of Dr. S.K. Nath (former Director General of the Central Statistics Organisation) argued that “Without counting of VVPAT paper slips in a significant percentage of polling stations in each constituency, the objectives of verifiability and transparency in the democratic process would remain unrealized”. Incidentally, Dr. S.K. Nath had suggested that at least 30% cross verification must take place in a given assembly segment of 200 booths to achieve sufficient accuracy. This petition was eventually tagged with a batch of other petitions requesting the Supreme Court to issue similar directions with regard to the issues concerning EVM-VVPAT cross verification.

The order may be read here:

In the case of N Chandrababu Naidu vs. Union of India (Writ Petition (C) No. 273 of 2019) the petitioners were making the same demand for increasing the verification to 50% cross verification of VVPAT paper slips with EVM vote count. Delivering the judgement in this case on April 8, 2019, the Supreme Court bench of Justice Ranjan Gogoi, Deepak Gupta, and Sanjiv Khanna increased the cross verification from 1 EVM-VVPAT cross verification to 5 per Assembly Constituency. In observed in its verdict that “If the number of machines which are subjected to verification of paper trail can be increased to a reasonable number, it would lead to greater satisfaction amongst not only the political parties but the entire electorate of the Country”. The bench did not agree to the threshold of 50% cross verification after taking into account the additional requirement of manpower and possibility of delay in the declaration of the results by 5-6 days.

The order may be read here:

Related:

EVM Malfunction: Does Criminalisation Deter Genuine Complaints?

Is the Indian EVM & VVPAT System free, fair, fit for elections or can it be manipulated?