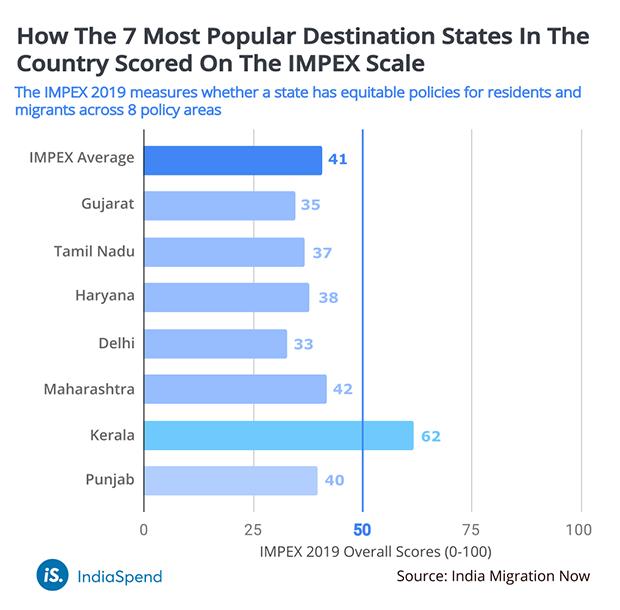

Mumbai: Kerala ranked first out of seven states for migrant friendly policies on the Interstate Migrant Policy Index 2019 (IMPEX 2019), an index compiled by India Migration Now, a Mumbai-based nonprofit, which analyses state-level policies for the integration of out-of-state migrants.Maharashtra ranked second with a score of 42 out of 100 compared to Kerala’s 62, and Punjab came in third with a score of 40.

Ram Das, pictured outside his hut at a brick kiln in Nizamabad district, is a Marathi worker in Telangana.

Internal migration, both within a state and across states in India, improves households’ socioeconomic status, and benefits both the region that people migrate to and where they migrate from, research shows. Yet, interstate migration in India is less than in other countries at a similar stage of economic development, studies show. A 2016 World Bank study attributed this partly to the migrant unfriendly policies in many parts of the country.

The low level of migration, especially between Indian states, partly resulted in the country’s low urbanisation rate –31% in 2011. This rate is lower than in countries with lower per capita gross domestic product, such as 51% in Ghana and 32% in Vietnam, based on data accessed from Our World in Data, an open data website.

India ranked last in a sample of about 80 countries, in a cross-country comparison of internal migration rates between 2000 and 2010 by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

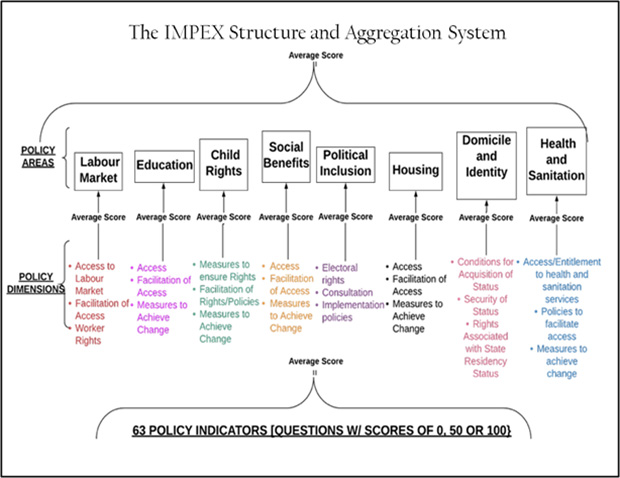

The IMPEX 2019 measures whether a state has equitable policies for residents and migrants in terms of: labour policies, child welfare, housing, social welfare, education, health, sanitation, and political participation. It also measures whether a state has additional and ad-hoc policy initiatives wherever needed for migrants to have equality with state residents. The index contains 63 policy indicators across eight policy areas, framed as questions or queries, in order to understand the extent of integration of interstate migrants in a particular state.

Apathy towards migrants in states might restrict migration

The principles of free migration are enshrined in clauses (d) and (e) of Article 19(1) of the Indian Constitution and guarantee all citizens the fundamental right to move freely throughout the territory of India, as well as reside and settle in any part of India.

Further, as the population ages in certain states such as Kerala, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu, they will have a higher number of elderly dependents and fewer working adults. At the same time, young states such as Bihar and Uttar Pradesh will have an abundance of working adults. To sustain their economy, ageing states will have to attract migrants from younger states.

But the results of the IMPEX evaluation revealed widespread apathy and discrimination towards migrants by state-level policymakers.

A lack of the possibility of integration in the destination state might dissuade migrants from moving to another state. The benefits of central government schemes are often relayed to citizens through state or local governments (for example: the Public Distribution System), which can make them available only to their permanent residents or “domiciles”. In such a situation, interstate migrants lose their entitlements when they cross the borders of their native states.

Source: Census 2011

Note: Andhra Pradesh includes data of Telangana.

Every state in India has reservations for the state’s residents or domiciles in areas such as public sector employment, tertiary education and social welfare schemes such as the public distribution system for foodgrains. Almost all states are apathetic to the needs of migrants, which stops the latter from accessing jobs, education, welfare entitlements, housing, health benefits and even voting in elections.

Often, even if states make provisions for migrants’ access to benefits and support, no measures are put in place to make migrants aware of the relevant schemes and policies or to facilitate this access.

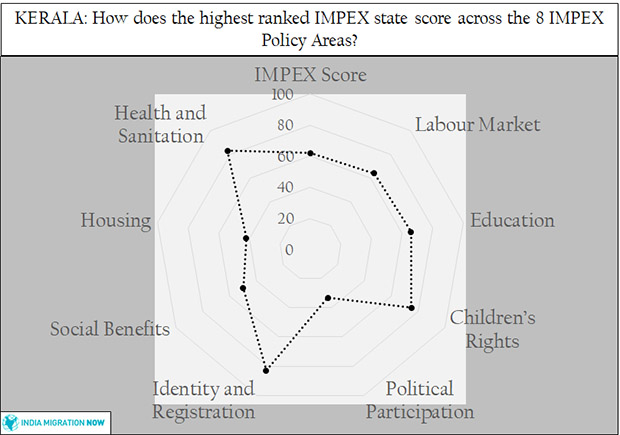

Why Kerala scores high on the migration index

Of all the states evaluated, Kerala’s policies are relatively more considerate towards internal migrants and their needs than other major migrant-receiving states.

Migrant-specific labour welfare schemes, health provisions and child policies are all a part of Kerala’s state policy architecture. Initiatives such as issuing alternative identity cards to provide education and welfare services to its migrant workforce, locally called “guest workers”, are unique in India. Such consideration of workers adds to the legacy of Kerala’s labour-friendly political and institutional ecosystem as well as its own long-standing migration relationship with the Gulf countries, where 89.2% of Keralite emigrants go.

These policies are also responding to its demographic transition–having gone through a period of a growing working population, Kerala now has an ageing population–and labour market needs of the Kerala economy. Such an inclusive environment is partly why Kerala has longer and more permanent migration of entire households into the state, especially from West Bengal and the North East.

Although Kerala consistently scores above the IMPEX average in all policy areas, considerable improvement is also needed. Absence of efforts to facilitate the political inclusion of migrants and ensure non-discriminatory access to housing brought down the state’s overall score.

Even states with high number of migrants have migrant-unfriendly policies

Delhi, Gujarat, Haryana, Kerala, Maharashtra, Punjab and Tamil Nadu have been the major destination states for migrants in India, according to 2011 Census data. But migrants face huge challenges and barriers in these states as their agency is constrained and they are left completely dependent on their networks and employers for their livelihoods.

Migrants have little or no state-level support and are often scapegoated by local law enforcement and politicians for any trouble. They are underpaid, underserved and unable to be fully productive.

Interviews with interstate migrants across India revealed widespread despondency about their quality of life and a yearning to go back home eventually.

One such respondent was Ram Das, a Maharashtrian local, who migrates annually with his family, to work in the brick kilns of Nizamabad district in Telangana. Ram’s family, along with several families from their native city of Latur, live in huts they build at the brick kiln site. When in Telangana, Ram’s children go to the local school and now speak better Telugu than Marathi.

Though his children can access education, his family cannot access healthcare and social security in Telangana because he is not a resident of the state. Thousands of migrants like him contribute to the economic growth of their destination states but get few social welfare benefits there.

Overall, Maharashtra, Punjab and Haryana have a slightly better policy scenario for migrants as compared to Tamil Nadu, Delhi and Gujarat.

For instance, in the housing policy criteria, Punjab scores 42 while Gujarat scores 17. Punjab’s Inter State Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Work) Rules, 1983, compel contractors to arrange accommodation for their migrant workers. In addition, Punjab’s Shehri Awas Yojana provides accommodation to slum dwellers, benefiting migrants as well.

However, in Gujarat, migrants only get assistance to build rest sheds and permanent residential housing with no measures for facilitating and ensuring the outcomes of this assistance, while provisions for housing available to the rest of the population exclude migrants.

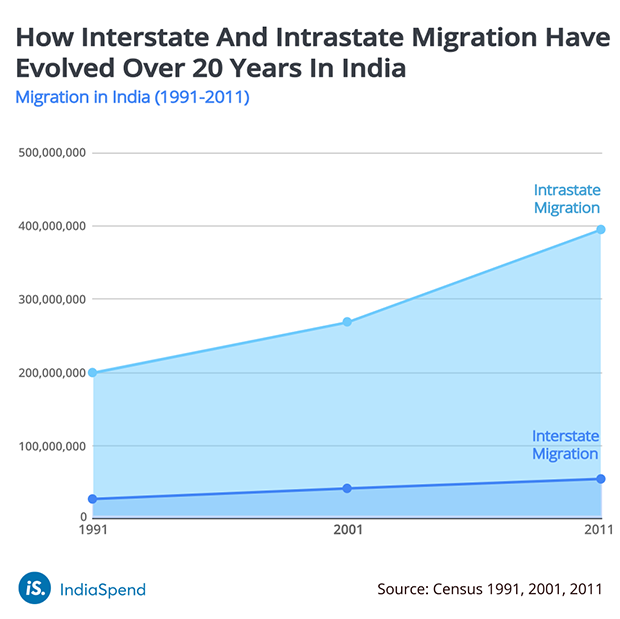

Interstate migration in India increased after 1991

However, despite all the barriers, interstate migration in India has increased in the past two decades from 11.08% as per Census 1991 to 12.06% per Census 2011. Yet, it still remains less than intrastate migration. This increase is in part because of falling poverty levels (wealthier people migrate across states more).

But it is also a reflection of the widening interregional income and wealth gaps in India than of an improvement in migration policy. With high inequality between incomes, and increasing aspirations, households are migrating longer and further in search for alternative occupations and lifestyles. Most interstate migrants end up in urban destinations (where most of the alternative jobs and lifestyles are), while intrastate migration is typically into other rural areas within the state.

Source: Census 1991, 2001, 2011

Within state migration larger than interstate migration in India

In 2009, the Indian labour force consisted of 100 million internal labour migrants, as estimated in a 2009 study conducted by Priya Deshingkar and Shaheen Akter. Even with no increase in these numbers between 2009-2018, migrants would comprise at least 19.6% of the Indian labour force today. In 2009, migrants also contributed 10% of India’s GDP, according to the 2009 study.

Short term (1-3 month) seasonal migration within states, often within the same district, is the dominant migration strategy in India, based on current research. “Average migration between neighbouring districts in the same state was at least 50% larger than that of neighbouring districts on different sides of a state border,” said a 2016 World Bank study.

There are many reasons for the dominance of intrastate migration, but the chief reasons are the predominance of low-income households with limited asset base, the limited size and localised nature of social networks inadequate for facilitating longer distance migration, and the prohibitive costs and risks involved in migrating to far away regions–akin to traveling to another country.

Typically, people from low-income and historically backward communities migrate for shorter terms and shorter distances, usually within the state itself, while interstate and international migration are dominated by more affluent and privileged households, based on India Migration Now’s review of micro-studies in India and the wider international academic consensus.

(Aggarwal, Singh and Mitra are researchers from India Migration Now, a Mumbai-based migration data, research and advocacy non-profit.)

Courtesy: India Spend