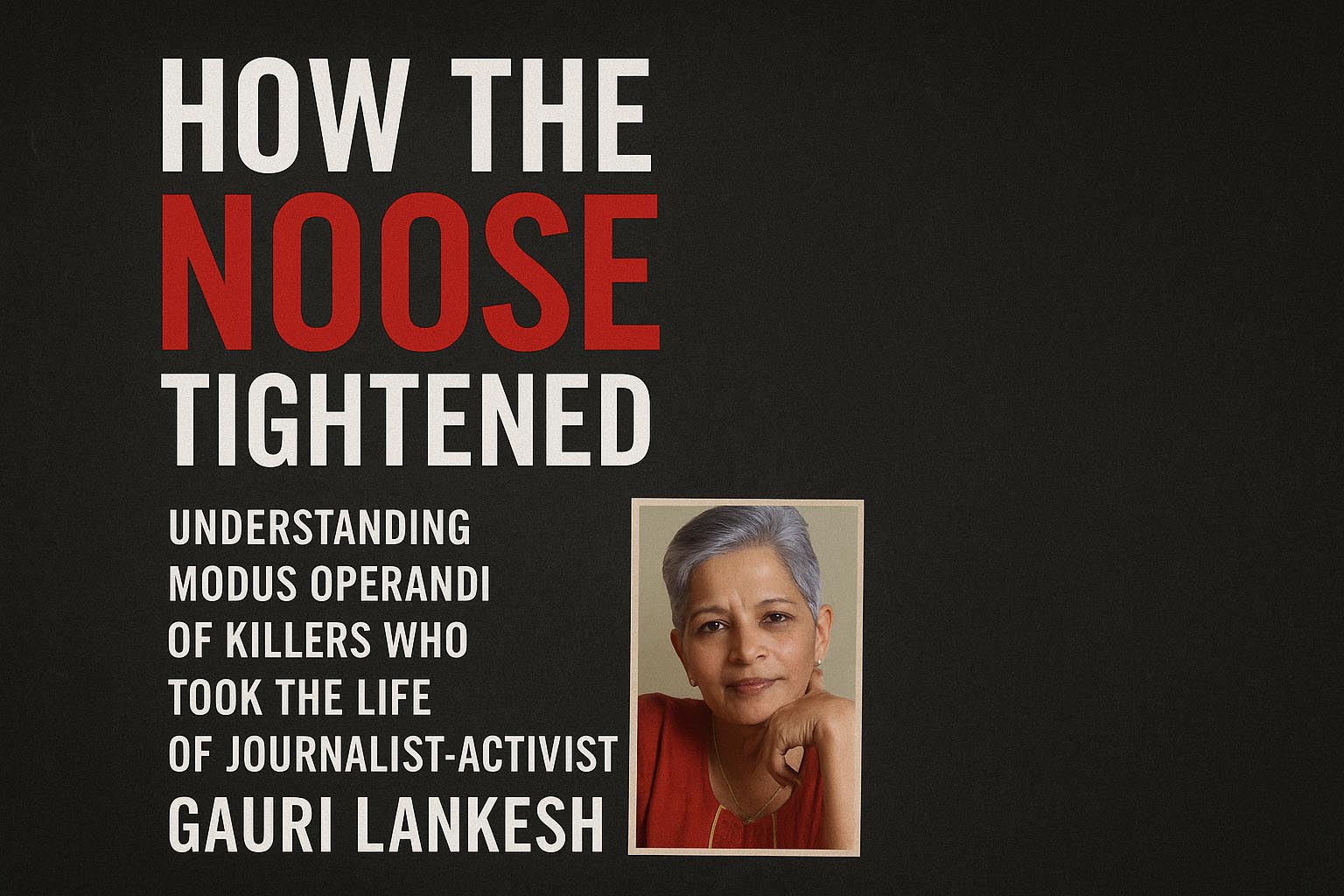

This fourth and concluding excerpt from the much acclaimed book by Rollo Romig, an American journalist (2024) who lived in Bengaluru (Bangalore) and knew Gauri Lankesh, I am on the Hit List, deals with the minute modalities of how the conspirators and killers –who functioned in well-defined cylos, functioned – all linked by thought and ideology to an organization called Sanatan Sanstha accused of being the mastermind that influenced the killings of four rationalists, Narendra Dabholkar (August 20, 2013) Govind Pansare (February 19, 2018), MM Kalburgi (August 30, 2015) and Gauri Lankesh (September 5, 2017). This excerpt also draws from the 9,235 page charge sheet filed by the Special Investigation Team (SIT) responsible for the intrepid investigation into the Gauri Lankesh murder and gives us a minute understanding on how the plot(s) to kill were executed

This excerpt, the fourth and the last d in a series of four that Sabrangindia is publishing, looks at the methodology employed by the conspirators and killers of four rationalists, including Gauri Lankesh. The editors remain thankful to the author and to Westland Books for permission to publish this excerpt.

CHAPTER 20

The Nameless Group

In 1986, the Kannada novelist, U. R. Ananthamurthy wrote a nuanced essay about religion and superstition titled “Why Not Worship in the Nude?” (Its title is a reference to a controversial Hindu sect whose adherents pray unclothed.) The essay teems with complexities and questions, including the following: “Haven’t I become what I am by de-mythifying, even desecrating, the world of my childhood? As a boy growing up in my village, didn’t I urinate stealthily and secretly on sacred stones under trees to prove to myself that they have no power over me?”

The essay was little known until June 2014, when M. M. Kalburgi referred to the quoted passage in a speech. This time it landed in a political climate that hungers to be offended, and this passage of Kalburgi’s speech attracted wide media attention. But the media (including Sanatan Sanstha’s daily newspaper) immediately got two things very wrong: first, it was reported as Kalburgi describing his own childhood experience, not referring to Ananthamurthy; second, it was reported that he’d urinated not on sacred stones but on Hindu idols, a far more grievous act of desecration. Some even claimed that Kalburgi had urged his audience to urinate on idols. A brief, contextless video clip of this bit of Kalburgi’s speech played repeatedly even on mainstream TV news channels and circulated widely online.

It was this episode—this garbled reporting of a literary reference that Kalburgi made once—that motivated his assassins to murder him, the SIT found. The killers didn’t care about, and never read, the hundred books he wrote. They were indifferent to his stance on the Lingayat issue. His entire life’s work and thought were reduced for them to this one misunderstood moment, then whipped up into an offense so intolerable that they could not permit him to live.

Dabholkar and Pansare seem to have been murdered for more obvious reasons: their insistent campaigns against superstition, which right-wing Hindu groups saw as a direct threat to their religion and culture. But why did they murder Gauri?

In India it is common for police complaints to be filed against people for “hurting religious sentiments,” a phrase that is perhaps unique to India and that is frequently invoked in the news media. The relevant law, Section 295A, is obviously well meaning: religion is a volatile subject in India, so a disincentive to needless religious provocation seems wise. In practice, though, Section 295A seems to have encouraged a very vocal minority from all religions to develop a hair-trigger sensitivity to any potential insult (including satire, legitimate criticism, unintended implications, and innocent misstatements), and even to seek out opportunities to be offended, because the law seems to enshrine an actual right not to be offended, at least when it comes to religion.

In its charge sheet, the SIT concluded that the assassins’ motivation for killing Gauri was very specific: a single speech she gave, in Kannada, at a Communal Harmony Forum event in Mangalore, on August 2, 2012. “What is this Hindu religion?” she said in the speech. “Who is the founder of this religion? We know the founder of the Christian religion and its holy book, we know the Muslim religion and also its holy book, likewise about the Sikh religion, the Buddhist religion, Jain religion, but who is the founder of the Hindu religion?…This is a religion without a father and mother and it does not have a holy book. It never existed, and it was named only after the British, can it be called a religion?”

A video clip of this speech circulated widely on YouTube and WhatsApp with the caption “Why I hate secularism in India.” And the SIT found that as each new member of the assassination team was inducted into the conspiracy, the ringleaders would show them this particular clip, often repeatedly, as the primary motivator of their will to kill. They told their recruits that in making these remarks, Gauri had “caused great damage” to Hinduism, and that further harm will befall Hinduism “if she is permitted to continue to speak this way.”

In December 2016, Gauri herself posted a link to the video, writing, “I am facing a case because of this speech. I stand by every word I said.” Police had booked her for what she said in the speech, not under Section 295A, but under Section 153, incitement to riot (although there had been no riot). A court hearing in the case was scheduled for September 15, 2017, ten days after her death. Her friend Vivek Shanbhag told me he saw this clip circulate much more widely on social media after her murder—“certainly to convey that this is justified.” These re-postings were often captioned with lines like of course killing is wrong, but look at what she said.

It wasn’t important to the killers even how influential their targets were. They themselves had mostly never even heard of Gauri until they were shown this video. The important thing was whether the target had done or said something—even a single quotation, and ideally captured on video—that could crystallize outrage against the target. It turned out that it wasn’t about suppressing unfavorable journalism, and it wasn’t about the Lingayat debate. (The killers didn’t care about vote-bank politics.) It was because the killers simply believed they had a duty to kill those who had, in their view, intolerably insulted Hinduism, regardless of their stature and influence. As the Sanatan Sanstha book Kshatradharma Sadhana put it, the seekers had to slay the evildoers.

Beyond that imperative, it seemed to me that the killers weren’t strategic at all in their choice of target, although Gauri’s friend Shivasundar disagreed with me. “I think they have multiple strategies,” he said. “One of the strategies is to kill the local problematic people. They may not be high profile, but they are an immediate impediment. Writing in local languages, immediately they’re a threat. They did not think that Gauri would have so much national and international attention, because they didn’t do much homework on Gauri, I don’t think. So this actually blew up beyond their imagination. It boomeranged. But other people in the target are local, state- level kind of leaders. I think that is the new strategy, assassinating these kinds of people.”

There is no concept of blasphemy in Hindu scripture. It’s an idea that comes from the Abrahamic tradition. Christianity and Judaism seem to have retreated from it, by and large. But Hindutva has adopted it; in recent years Sanatan Sanstha has been agitating for an Indian anti-blasphemy law. Hindutva hard-liners, in defense of their touchiness, often point out how touchy many Muslims are over any negative comments on Islam or Muhammad, which is of course true. But it’s a strange thing to aspire to the touchiness of the most insecure Muslims. A great deal of Hindutva seems to be geared toward imitating the most reactionary qualities of the religion (Islam) and the country (Pakistan) that they claim to hate the most.

It’s important to note that the current level of Hindutva sensitivity is a recent development. Gandhi was assassinated not because of particular things he said but because the Hindu right wing thought that he’d used his enormous influence over the future of South Asia to “appease” its Muslim population en masse and thereby, supposedly, give away half the country (in the form of Pakistan). The author of the Indian Constitution, B. R. Ambedkar, converted to Buddhism in 1956 along with hundreds of thousands of his fellow Dalits. “I am ecstatic! I have left hell—this is how I feel,” he said the next day. “Because of the Hindu religion, no one can progress. That religion is only a destructive religion.” Those words haven’t stopped the BJP and RSS from attempting to co-opt his legacy in the hopes of attracting a Dalit following. K. S. Bhagawan, the next person the assassins planned to kill, pointed out to me that he’d been saying inflammatory things about Hinduism for decades; only recently did anyone threaten to murder him over it.

Still, several of Gauri’s friends and colleagues told me that while obviously she deserved no harm for anything she said, they didn’t honestly like that she could be so pejorative about Hinduism instead of reserving her criticism for Hindutva. “I really think that the way Gauri, or some of us, or many such people addressed these issues was not correct,” said H. V. Vasu— a progressive activist whose secular credentials are impeccable. “You may be an atheist, but there are people who are religious. And especially when irrationality is growing, and more and more people are going to the other side—even common people who are actually voting for an ideology that oppresses them. Then what approach should you take? You should stick to your ground in fighting for democratic rights, secularism, all that is true. But people do need God. Even when Marx said that religion is opium, there were other sentences attached to it—he said that religion is the heart of the heartless world and the soul of the soulless world. There’s so much suffering and insecurity in this world. You must acknowledge that people have spiritual needs.”

On New Year’s Day 2012, in the northern Karnataka town of Sindagi, six young men were arrested for hoisting the national flag of Pakistan on the flagpole in front of a local government office. The men were members of the fringe Hindutva group Sri Ram Sena; their intention was to whip up tensions with the local Muslim population. The man who actually hoisted the Pakistan flag was a twenty-year-old college student named Parashuram Waghmare. Five years later, he would shoot and kill Gauri Lankesh. The ringleaders of the group who conspired to kill her recruited him precisely because of the initiative he’d shown in the flag-hoisting incident.

Waghmare had never heard of Gauri until those conspirators told him they wanted him to kill her and showed him the video of her speech. But Gauri, oddly enough, had heard of Waghmare. His flag-hoisting escapade was notorious in Karnataka. In the January 28, 2012, issue of Gauri Lankesh Patrike, she even wrote about it for her lead editorial. “It has been proven now that patriotism, nationalism, and religiousness are simply a few table topics” to Hindutva activists, she wrote. “Their true agenda has been to instigate communal hate between different religions of India through acts of terrorism.” She called Waghmare and his accomplices “Hindu hooligans.” Her next issue’s cover story was an investigation into the flag-hoisting incident by one of her reporters.

But another group was already rising, one that Gauri knew nothing about yet. I derived all of the information in the following account of that group from the 255 pages of statements of the accused included in the SIT’s charge sheet, as well as newspaper articles by Johnson T. A. of The Indian Express and K. V. Aditya Bharadwaj of The Hindu, who are universally considered the two most accurate and reliable reporters on the assassination of Gauri Lankesh. At the time I’m writing this, the trial against these suspects is ongoing, and every sentence that follows should be presumed to include the word “allegedly.”

The founder of the assassination organisation that murdered Dr. Narendra Dabholkar, Govind Pansare, M. M. Kalburgi, and Gauri Lankesh was Dr. Virendra Tawade, an ENT surgeon who had been a longtime member of Sanatan Sanstha. Tawade had led Sanatan Sanstha’s protest campaign against Dabholkar’s anti-superstition organization, MANS—one medical doctor versus another. Tawade founded the assassination group at the urging of Shashikant Rane, alias Kaka, the top editor of Sanatan Sanstha’s newspaper, Sanatan Prabhat. In 2010 or 2011, Rane convened a meeting at the Sanatan Sanstha ashram in Goa with Tawade and two other Sanatan Sanstha members: Amol Kale and Amit Degwekar. Amol Kale was a leader of the Sanatan Sanstha’s offshoot Hindu Janajagruti Samiti and served as a salesman of the organization’s publications. Amit Degwekar lived at the Goa ashram and worked as a promoter and proofreader of Sanatan Prabhat. His roommate at the ashram had died in 2009 when he accidentally detonated his explosives while attempting to bomb the festival in the nearby town of Margao.

Dr. Tawade was founding the new group, Rane told Kale and Degwekar at the meeting, because “Hindu dharma is in trouble.” The law would clearly not protect their interests, so they needed to take the law into their own hands. Hindu youth must be gathered, a sense of revolution must be instilled in them, and they must carry out the religious work of destroying evildoers. Dr. Tawade was not giving the organization a name, Rane explained, because a name would only make it easier for the police to identify and thwart them. Rane would remain in his role at Sanatan Sanstha and help fund the new nameless group (until he died in 2018, inconveniently for the SIT). The other three men at the founding meeting—along with two other early members of the group, Sujith Kumar and Vikas Patil—would henceforth disassociate themselves from Sanatan Sanstha. Degwekar would serve as liaison between Sanatan Sanstha and the new, nameless group, as well as its treasurer.

Over the next few years, as they enlisted dozens of recruits, the Nameless Group developed a strict set of protocols. To aid focus and avoid mistakes, chant mantras every day. When mistakes occur, write them down. When meeting other members of the Nameless Group, don’t request or share anything personal, including line of work, and especially don’t ask or offer names or personal phone numbers; only call other members using specially assigned burner phones. Everyone would be assigned a code name, numbers would be written in a cipher, and all references to criminal activities would be conducted in code words.

It’s important to note that the co-conspirators barely knew one another. They often didn’t have fluent languages in common because they came from several different states. They met at bus stands, wearing caps to recognize one another, and at training camps in remote areas, where they received practical education in weapons (guns, petrol bombs, IEDs) and subterfuge (how to mislead the police; how to endure police torture). It’s only after they were arrested that most of them spent much time with one another.

One member was a used-car salesman. One was a goldsmith. One ran a fragrance shop; another ran a computer-assisted design company. One was a civil contractor and former elementary school teacher. One worked as an astrologer and Ayurveda specialist. One sold incense sticks; another was a vegetable vendor. The day job of another, incredibly, was personal assistant to a Congress Party legislator. One was a motorcycle mechanic, who, more to the point, was also a skilled motorcycle thief. The mechanic said that when Dr. Tawade met the new recruits, “he filled our heads with all his thoughts. He kept emphasizing the point that if we did anything for dharma, our family would be safe in all the seven lives to come.”

Sharad Kalaskar, who was selected to shoot Narendra Dabholkar, worked as a farmer. After Kalaskar committed the deed, on August 20, 2013, Dr. Tawade told him that he would be uplifted in all seven births, that he would go to God as Arjuna (one of the warrior heroes of the Mahabharata), and that even though he had committed a big “event”—their code word for “attack”—the police would not catch him because God’s grace was upon him.

Around that time, several members held a meeting to brainstorm whom they might kill next. One new recruit—Mohan Nayak, who served as a leader of the Karnataka branch of the Sanatan Sanstha offshoot HJS—made a list that included a supposed Naxalite, a Muslim politician, and Agni Sreedhar. A more senior member explained to him that he should not include Muslims, Christians, or politicians on the list; their priority, he explained, should be Hindus by birth who had become traitors to Hinduism and who were therefore threats to their own faith. Such people were bigger threats to the faith than Muslims. Nayak got the idea and suggested a different name: Gauri Lankesh.

But that would wait. On February 16, 2015, the Nameless Group killed Govind Pansare. On August 30, 2015, they killed M. M. Kalburgi; for this killing, the shooter was Ganesh Miskin, alias Mithun, who would go on to drive the motorcycle for the Gauri Lankesh assassination.

On June 10, 2016, the Central Bureau of Investigation arrested Dr. Tawade for Dabholkar’s murder—three years after Dabholkar’s murder and two years after the CBI had taken over the investigation from the Maharashtra police. After the arrest, Rane, the editor of Sanatan Sanstha’s newspaper, summoned Tawade’s deputy, Amol Kale, to the Goa ashram and made him the new head of the Nameless Group. “You take up the lead of the dharma work and continue,” he said. “We’ll provide you with all the assistance from time to time.”

In June 2016, the group’s main recruiter, who goes by the alias Praveen, showed the other senior members the video clip from the speech Gauri had delivered in Mangalore in 2012, in which she ridiculed Hinduism for not having a “mother or father.” In the last week of August they called a meeting with several junior members of the group, at which they discussed the Sanatan Sanstha book Kshatradharma Sadhana and each drew up lists of evildoers. They soon coalesced around Gauri as their next target. Kale’s diary revealed the group’s code name for their plot to kill Gauri: Operation Amma (“amma” meaning “mother”).

Kale introduced a different operational style to the Nameless Group. Whereas Tawade’s plots were straightforward—case the victim’s house, then show up and shoot him at an opportune time—Kale’s plot against Gauri was much more elaborate and compartmentalised, with separate teams running each facet of the operation. They were more careful than ever, but also more confident.

In October 2016, the Nameless Group enlisted Parashuram Waghmare. They had been particularly impressed by Waghmare’s arrest for hoisting the Pakistan flag. They told him there was someone who needed to be murdered and urged him to meditate and pray. That same month, the group’s mechanic stole the Hero Honda Passion Pro motorcycle that the hit team would use for Gauri’s murder and gave it to Amol Kale.

Meanwhile, Kale gave Gauri’s office address to two of the younger recruits—Ganesh Miskin and Amit Baddi—and assigned them to do reconnaissance. In late March they traveled to Bangalore, stayed at the house of a friend (lying to him that they were in town for work), borrowed the friend’s motorcycle, and tailed Gauri for a couple days. In April they met Kale again, gave him her home address, and reported that she lived alone. The best time to kill her, they said, would be when she gets out of her car to open her house’s gate. Throughout the summer of 2017, these three men were crawling all over her neighborhood for weeks, continuing to study her movements, surveying all lights and CCTV cameras near her house, practicing multiple variations on routes, absorbed invisibly into the traffic of Bangalore. In July they brought Waghmare on a reconnaissance visit to Bangalore, but blindfolded him so that he’d know as little as necessary.

Throughout that summer the group also did firearms practice at a remote farm shed owned by one member, using a polystyrene mannequin as their target. They mostly used air pistols because real bullets were in short supply. Between shooting and karate they did meditation and yoga.

In June 2017, they recruited the final member of the team: K. T. Naveen Kumar, the one who slipped up first and gave them all away. That month, at the annual Sanatan Sanstha convention in Goa, he gave the impromptu speech, about the need to use weapons to protect Hindu dharma, that had so impressed his fellow convention goers. The HJS spokesperson Mohan Gowda then introduced him to Praveen, the Nameless Group’s recruiter. When they first met, Naveen Kumar gave Praveen two bullets, but came up empty when the group asked him again and again for more. Naveen Kumar talked big, but those two bullets were his only apparent contribution to the plot.

In the second week of August 2017, members of the Nameless Group stayed in the Bangalore suburbs for several days. There Kale gave them their assignments. Waghmare was assigned to shooting. Miskin was to drive the motorcycle on “event” day and to be the backup shooter—and also to shoot anyone who tried to interfere with the assassination. Baddi was to wait in a van en route to Gauri’s house to help the hit team with their clothes and guns, to retrieve the guns and clothes from them immediately after the “event,” and then to bring the guns and the motorcycle to the city of Belgaum. Kalaskar, who shot Dabholkar, was to continue training Waghmare and Miskin in shooting and to collect the guns from Baddi in Belgaum. A member named Bharat Kurne, code-named Uncle because he was a family man, was assigned to cook for the hit team, to ensure they got out of town on a bus on the night of the “event,” to bribe police if necessary, and to help keep the hit team’s minds “stable” by leading them in meditation and prayer.

After shooting practice, Waghmare selected the gun that he was most comfortable with, which happened to be the same gun that shot Pansare and Kalburgi. Miskin told Waghmare that he shot Kalburgi in the forehead and Waghmare should shoot Gauri in the forehead, too. Baddi advised Waghmare to chant God’s name while shooting, as is recommended in the Sanatan Sanstha book Kshatradharma Sadhana.

On September 2, 2017, Kale and another member traveled to Bangalore along with the hit team’s clothes, two guns, and twenty-five bullets. For the week of the murder, the Nameless Group had set up two hideouts in the southern suburbs of Bangalore. The core hit team—Waghmare, Miskin, Baddi, and Kurne—stayed together. When Waghmare was brought to that hideout, on September 3, the others again blindfolded him so that he wouldn’t know where it was.

September 4, 2017, was the day they chose to kill Gauri. The hit team woke up early to pray for an hour or two. Kurne cooked them lunch. As the time for the “event” approached, he instructed the hit team to use the toilet, to eat little food, and to carry cash. At around 6:30, Miskin gave Waghmare a pistol and kept one for himself. On the way to Gauri’s house, they stopped to put on their second layer of clothes and cover their faces with handkerchiefs and put a fake license plate on their motorcycle and load their guns. They arrived at the park near Gauri’s house at around 7:45. They waited there until 8:00, and then Waghmare walked over to Gauri’s house and found that she was already at home.

On September 5, 2017, they tried again, following the same plan and arriving at the park near Gauri’s house at around 7:50. When Gauri’s car appeared, taking a right turn by the park, Miskin pointed her out to Waghmare. They followed her on the motorcycle. When she got out of her car to open her gate, Waghmare stepped down from the motorcycle, aimed his gun at her head, and fired, striking her twice in the abdomen. She screamed and ran. He fired two more bullets, one of which struck the wall of her house, the other hitting her below the right shoulder. Meanwhile, Miskin turned the motorcycle around. He and Waghmare fled, stopping to reverse their disguises on the way back to the hideout. The gun was out of Waghmare’s possession fifteen minutes after the murder; he passed it to Baddi, who passed it to Kale, who wrapped it up and put it in a red suitcase, which went into a storage space rented for that purpose. At the hideout, Kurne was waiting for the killers with their luggage to get them to the bus out of town.

Half of the accused conspirators were outside Bangalore on the day of the assassination and only learned of its success the next day. On September 7, at a construction site in Belgaum, Kale met the core assassination team— Waghmare, Miskin, Baddi, and Kurne. He fed them chocolates and gave Waghmare 10,000 rupees, or around $150. Waghmare soon spent it all, 4,000 rupees of it on hospital treatment for nasal problems.

By October 2017, the Nameless Group had turned to the next item on their list: the assassination of Professor Bhagawan. In the first week of November 2017, most of the conspirators met at Kurne’s farm for further training and discussion of plans. As usual, their training session alternated between weapons training and dharma talks, prayer, and meditation. Despite the successful assassination in September, Kale appears to have been increasingly frustrated with his co-conspirators. He reprimanded one for not being in Bangalore to help during the “event.” He was angry at two others because he assigned them to do reconnaissance for three days on a social activist in Pune, but they came back with nothing.

Meanwhile, Praveen, the group’s recruiter, had been calling K. T. Naveen Kumar about the plot to kill Bhagawan, again asking him if he could procure more guns and bullets. Naveen Kumar told him he’d do literally anything to protect dharma and bragged, implausibly, that he could get guns from the late bandit Veerappan’s gang with a week’s notice. It was these phone calls that the SIT intercepted, giving them their big break and beginning their series of arrests.

In December 2017, led by Kale, ten members of the Nameless Group met in Pune to organize a bomb attack on the Sunburn Festival, an electronic dance music event, because they considered it contrary to their idea of Hindu culture, but they abandoned the plan after two members accidentally got caught on CCTV cameras while doing advance reconnaissance. The following month, Kale organized an attack on movie theaters showing the historical epic Padmaavat, because it is, as Kalaskar put it in his statement, “a misrepresentation of the history of Hindu kings” and might encourage Muslim men to pursue Hindu women. “We intended to cause loss of property and create an atmosphere of fear,” he said. In this they were successful: the group exploded bombs at two movie theaters. No one was hurt, but panic broke out and screenings of the film were canceled.

Around this time, Naveen Kumar asked the senior members of the group to meet him in Davanagere because, he said, the “things” had arrived for killing Bhagawan. When they arrived, Naveen Kumar gave them the runaround for a while before admitting he still had no guns—there was apparently “no signal” from “his side” because “they did not trust us enough.” Kale was furious. After this, Naveen Kumar never again picked up their calls.

On February 19, 2018, Naveen Kumar was arrested. The senior members of the group had an urgent meeting in Madgaon. They decided to collect their weapons stashes and move them to a safer place, to shave any facial hair, to wear glasses and caps, and to hide out for a while in a different house. But Kale assured the other conspirators that the arrest of Naveen Kumar wouldn’t affect them; they should meditate and pray and prepare for more dharma work. While in hiding, Kalaskar accidentally shot himself in the hand while cleaning a gun.

On May 20, 2018, Praveen, the group’s recruiter, was arrested; police found twenty-two phones, and many more loose SIM cards, in his kitchen, along with his diary and a copy of the book Kshatradharma Sadhana. The next day, police arrested three others, including Kale, while they waited for Praveen at a bus stand; they didn’t yet know of his arrest. In Kale’s possession police found twenty-one phones, plus three diaries at his home. In the possession of Degwekar, the group’s treasurer, they found several envelopes of cash, totaling over 150,000 rupees, that had been withdrawn from a Sanatan Sanstha bank account, along with the passbook for that account. Degwekar claimed that the money was subscription payments from readers of Sanatan Sanstha periodicals. Police found that the various diaries referred to over two dozen collaborators with the Nameless Group in Karnataka and dozens more in Maharashtra—over sixty arms-trained and

radicalised recruits total (most of whom had not yet participated in any hit jobs). Intelligence agencies immediately put as many of them as they could under surveillance if they didn’t yet have the evidence to arrest them. These recruits mostly came from a tri-state area: southwestern Maharashtra, Goa, and northern Karnataka. The annual Sanatan Sanstha convention in Goa, it seemed, was their central recruitment hub, where they sought out young men with violent tendencies and a history of communal incitement.

After learning of Kale’s arrest, the members at large destroyed their burner phones. Mohan Nayak destroyed the bomb gelatin he was storing for future attacks. Kalaskar, the member who’d shot Dabholkar and who’d helped train Gauri’s killers, burned his phone and his three diaries, which included his notes on how to make guns and bombs. On June 11, Waghmare was arrested.

Kalaskar still had the guns. After Waghmare’s arrest, Kalaskar met with the Sanatan Sanstha lawyer Sanjeev Punalekar. To cover their tracks, they had an elaborate method of meeting: Punalekar’s assistant placed an ad in Sanatan Prabhat seeking a security guard, and Kalaskar answered the ad, whereupon the assistant took him to meet Punalekar at his office. Punalekar asked Kalaskar whether Gauri’s murder could be tied to Kale or Tawade, and he asked about the location of the guns. Two days later they met again, and Punalekar told him to destroy the guns used for killing Gauri along with their remaining stash of guns and bombs. “He also asked me how long it would take to make new guns,” Kalaskar said in his statement, “and he said he would pay the cost for making guns.” Punalekar asked Kalaskar extensively about the Dabholkar murder and “various cases,” and told him not to worry.

I will note here that the account of Kalaskar’s conversations with Punalekar in the above paragraph comes directly from a statement that Kalaskar dictated and signed before a magistrate, which means that it is admissible as evidence in court. Later, in 2019, the Central Bureau of Investigation would arrest Punalekar in connection with Dabholkar’s murder. The SIT investigating Gauri’s murder said they considered Punalekar a “person of interest” in that case for advising Kalaskar to destroy the guns, but they did not arrest him.

On July 18, 2018, Mohan Nayak was arrested. On July 23, Kalaskar disassembled the guns in his possession, including those used in Gauri’s murder, then, with the help of Punalekar’s assistant, threw the guns’ slides and barrels into Vasai Creek, near Mumbai, which empties into the Arabian Sea. He kept the remaining gun parts for making new guns, calculating, apparently accurately, that only the slides and barrels were ballistically identifiable. Over the next three weeks, the SIT arrested seven more members of the Nameless Group, including Kalaskar, Kurne, Miskin, and Baddi.

On August 19, 2018, the Maharashtra Anti-terrorism Squad raided the house of the assistant of the Sanatan Sanstha lawyer Punalekar and found an enormous cache of explosives, plus sixteen complete pistols and many partially made pistols and pistol parts. The ATS concluded that most of these pistols were made or obtained after the arrest of Naveen Kumar six months before, which suggests an alarmingly rapid rearmament of the Nameless Group, even while their members were being arrested. In the past the group had lain low for as long as two years between hits, to let things cool down. Kale apparently wanted to accelerate the group’s work, to assign multiple simultaneous assassination plots and bombings to several teams. The bust also implied that the group had grown large enough that it was possible that enough members remained free to regroup and kill again.

On August 20 and September 8, two more members were arrested. Now only two of the eighteen men charge sheeted for Gauri’s murder remained at large, both of them senior members of the Nameless Group. “Sanatan Sanstha has no connection with these killings. Due to propaganda by the Communist Party, the misunderstanding about us has been created,” said a Sanatan Sanstha spokesperson on September 6, 2018, the day after the first anniversary of Gauri’s death. “Violence was never, is never and will never find any place in the mission of Sanatan Sanstha, which believes in working in a constitutional manner.”

(The first excerpt was published some days ago and may be read here. The second excerpt may be read here.

The third excerpt was published too and may be read here. This is the fourth and concluding excerpt that we will be pulishing.)

Note from the Editors: We would like to express our heartfelt solidarity with the family of Gauri Lankesh, Indira Lankesh, Kavitha and Esha Laneksh, who have with pathos and determination built on the gaping vacuum created by Gauri Lankesh’s assassination. Gauri was also a close and dear activist friend of Sabrangindia’s co-editor, Teesta Setalvad.

Related:

Firing at the Heart of Truth: Remembering MM Kalburgi

Teesta Setalvad On Assault On Reason

Death of a Rationalist: Govind Pansare

Storms battered her from outside, but she stood, an unwavering flame: Gauri Lankesh

Gauri Lankesh assassination: 6 years down, no closure for family and friends, justice elusive