Death certificates and commemorative plaques aren’t something you’d normally associate with a glacier. But that is exactly how Iceland recently mourned the loss of 700-year-old Okjökull, the first of its major glaciers to die.

People gather to commemorate the loss of 700 year old glacier Okjokull. STR/EPA

This is just one early example of events we will encounter more and more often as the hot new world we are creating slowly destroys ecosystems and livelihoods. But acknowledging the growing emotional trauma and grief felt at present and future environmental tragedies may yet be the kick we need to limit their reach.

Grief radically differs in its logic from ordinary sadness over a loss. If sadness is the response to the removal of an object from the tablecloth that represents a person’s lived world, grief results from loss that tears the very fabric of that cloth. In order to repair this hole and emerge from the resulting pain and outrage, the lived world has to be reconfigured.

To grieve though, one must acknowledge the tear in that world. This can take time, and denial is a common part of the process of accepting deep loss. This may at first take the form of a temptation toward out-and-out disbelief, and linger as sporadic thoughts and hopes that what was lost, wasn’t.

It may seem an irrational reaction, but it’s a completely understandable defence mechanism against life-shattering loss. The world without what’s been lost is so radically and qualitatively different that the psyche resists accepting reality.

While much climate denial owes itself to corruption and vested interests, the avoidance of grief may explain why many decent and intelligent people are also tempted to deny the climatic breakdown humans are causing.

It is, in a certain sense, unimaginable, even absurd, to think of us destabilising our very climate, or the scale and speed of change required to stop the slide. It isn’t surprising that so many people have been desperately hoping that the science must somehow be wrong, or that so many more act as if we can still hope for the continuation of our same old world, rather than the fundamental shift in the way we operate and organise that’s required.

From grief to action

It requires sustained strength and attention to gradually turn denial into acceptance and to build a new life. Actions like Iceland’s glacier funeral are a vital part of that process. As symbols of eternity, glaciers have great cultural significance on the Nordic island. They’re also crucial for tourism and energy. And at current rates of warming, all of the country’s glaciers will suffer Okjökull’s fate in the next 200 years, one by one. For Icelanders, emotionally acknowledging this can galvanise the associated grief into action.

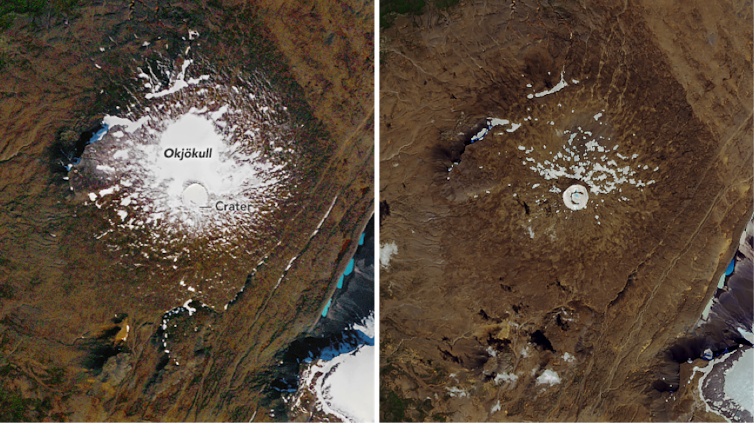

Left: Okjökull glacier in September 1986. Right: the now dead glacier in August 2019. Joshua Stevens/NASA Earth Observatory

It’s not an easy process, of course. As marks of our recklessness, the grief in cases such as this is particularly potent and often laden with anger, akin to that of someone close to a murder victim. This glacier ecosystem wasn’t “lost” – to speak of loss here is euphemistic. It was killed on our watch.

Grief over climate breakdown and the degradation of our natural world is also notably different from grief at the death of a loved one, because it never lessens, let alone goes away. The anthropogenic climate emergency will define our entire lifetime, and deeply impact on all of us soon enough. Because of time-lags in the climate system, things will get worse for a long time to come, whatever we do.

Thus, while a healthy reaction to the death of a loved one is to grieve deeply and then gradually to recover, the only recovery from ecological grief that is possible at all is for us to change the world such that our actions no longer deteriorate it.

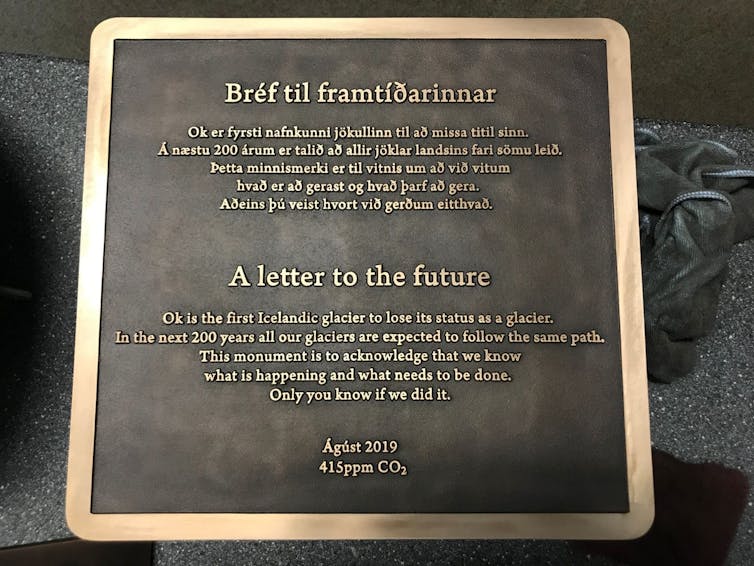

During Okjökull’s funeral residents reminisced, public figures such as Iceland’s Prime Minister Katrin Jakobsdottir spoke and presented a death certificate, and this plaque was laid. Grétar Thorvaldsson & Málmsteypan Hella/Rice University

This is how ecological grief – at the tearing from us of the natural systems we are neither willing nor able to do without – leads to the radical action necessary to bring about a new world.

Given how late the hour is, that means not accepting inaction any longer – and that’s up to us. In the words of Iceland’s commemorative plaque, laid at the base of the dead glacier as a message to the future: “We know what is happening and what needs to be done. Only you know if we did it.”

Courtesy: The Conversation