In March 2012, Sanjay and Sunita Ambhore, parents of Aniket Ambhore, 19, a first-year electrical engineering student at the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay (IIT-B), received a letter informing them that their son–admitted on a scheduled caste (SC) quota–had failed two courses.

Aniket Ambhore, a 22-year-old dalit student of electrical engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay fell to his death from the sixth floor of an Institute hostel in September 2014. Discrimination and derision based on caste can leave dalit students feeling that they are undeserving of their admission to higher-education institutions. Photograph provided by Sunita Ambhore.

Concerned, the Ambhores–Sanjay, a bank manager, is a dalit from Akola district, Maharashtra, Sunita, a junior-college lecturer, is not–met one of Aniket’s professors, who told them their son could not cope with IIT workload and would be happy in “normal” engineering colleges (with lower standards). He implied, they said, that scheduled caste students took up to eight years to complete a course that normally took four years. The professor suggested counselling to help Aniket focus on studies and named anti-depressants he could take.

The comments were a shock to Sanjay and Sunita, they said, who were until then mostly unaware that such attitudes existed in higher-education institutions.

Some high-caste professors consider dalit students “uneducable”, wrote educationist Kurmana Simha Chalam in an 2007 book, Challenges of Higher Education.

Reflected in Aniket’s response to his professor’s outburst, casteist expression can leave dalit students feeling that they are undeserving of their admission to higher-education institutions, concluded this 2013 King’s College London study of an Indian university, now a book, Faces of Discrimination in Higher Education in India: Quota Policy, Social Justice and the Dalits.

“Aniket did not find anything wrong with what he (the professor) had said, maybe because of the way it was said, as a well-meant suggestion,” Sunita told IndiaSpend.

Instead, Aniket–who scored 93% in his class 10 CBSE (Central Board of Secondary Education) board exam and 86% in his class 12 Maharashtra state board exam–possibly influenced by disparaging talk of affirmative action, told his parents that he wanted to reappear for the Joint Entrance Examination, the IIT admission test, which he cleared in 2011–and study engineering at an IIT only if he could crack the test without affirmative action.

Between then and August 2014, the Ambhores consulted three psychiatrists to help their son regain confidence. It made no difference. Gradually, the talented Aniket (click here to hear him singing at an IIT Bombay festival) turned into a student with low self esteem.

In August 2014, a joint meeting with Aniket’s head of department and the head of the Academic Rehabilitation Programme (ARP)—a programme for academically deficient students that Aniket had been enrolled in the previous year headed by the same professor they met in 2012–went particularly badly. The ARP head suggested that another exam failure would devastate Aniket, so it would be best if he dropped out, perhaps joined an NGO and considered a career as a teacher.

On September 4, 2014, Aniket fell to his death from the sixth floor of an IIT-B hostel. It isn’t clear if it was an accident or he jumped.

Some bias does show up on campus: IIT Bombay director

Media reporting of Aniket’s death–such as this September 6, 2014, report in the Times of India–suggested he struggled with academics, but did not mention that his parents “had repeatedly asked the HoD (head of department) if there was any way of reducing the academic load on Aniket”, to quote from their 10-page testimony submitted to IIT-B after his death.

Despite asking, they were not informed about the possibility of converting the dual degree M Tech programme Aniket was enrolled for to a shorter B Tech programme.

Aniket’s death was described as an accident and reporting included comments from unnamed friends that he did not appear to be “anybody who would commit suicide”.

Media reporting also did not mention Aniket’s growing preoccupation with religion and spirituality–he was raised in an atheist household–as he tried to navigate academics and his SC origins.

The IIT system provides for an SC/ST adviser for the redressal of caste grievances, and there is acknowledgement that caste plays some role in the life of SC students (and tribal students, for whom an additional 7.5% of seats are reserved).

“Some caste bias does shows up on campus, mostly as upper-caste students expressing their discontent with the reservation system,” Devang Khakhar, director of IIT Bombay, told IndiaSpend.

Questions have arisen over the efficacy of the redressal of caste grievances. Filmmaker Anoop Kumar of the 2011 documentary Death of Merit said that 80% of those who committed suicides in the IITs between 2007 and 2011 were dalits, and none of these institutes had a grievance-redressal mechanism to address caste-based discrimination.

Sunita now wonders if Aniket’s downward turn began when he stepped into IIT-B as a dalit, within months believing his academic woes were a result of his inability to reconcile with his origins. This left him with the belief that he was undeserving of a seat at India’s premier engineering college–an attitude confirmed by the King’s College London study.

Could it have helped Aniket if there were at least some professors who shared his background? There are, for a start, very few dalit professors in India’s 23 IITs.

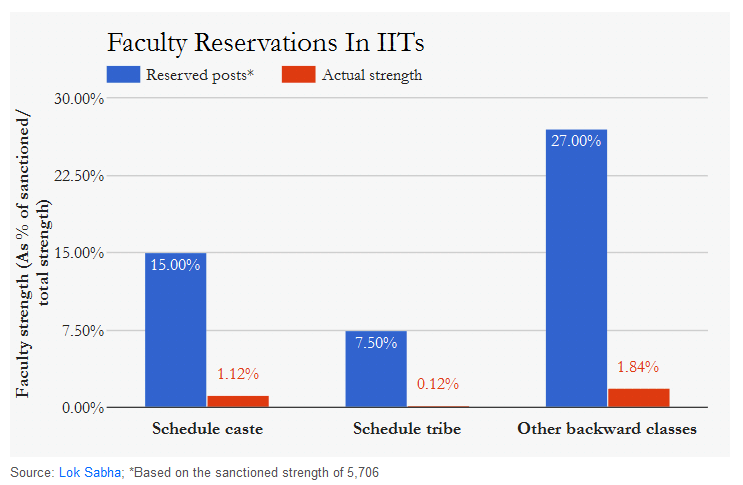

1.1% of IIT faculty is dalit. Would more make a difference to dalit students?

The quota system policy was designed in the 1950s as an early form of affirmative action to ensure that higher education institutions retained 15% of their places for dalit students; the same proportion of faculty was also expected to come from this background.

–Faces of Discrimination in Higher Education in India: Quota Policy, Social Justice and the Dalits

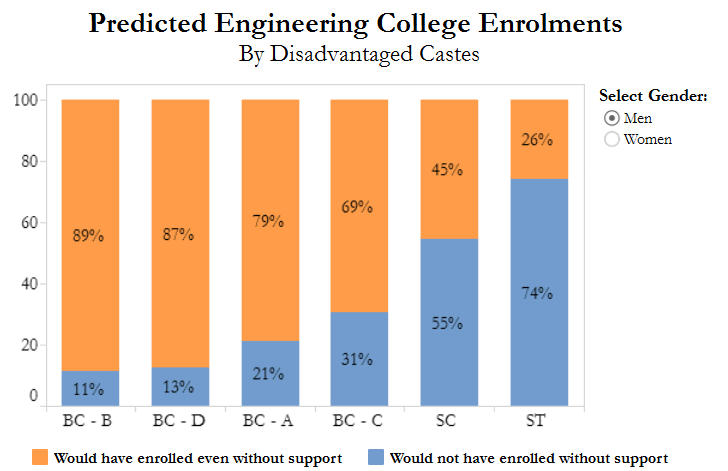

In July 2016, IndiaSpend reported how affirmative action helps students from disadvantaged backgrounds get college admission.

Source: American Economic Review

Hover over the chart for more details.

BC-A, BC-B, BC-C, BC-D refer to sub-categories A, B, C, D of Backward Caste. SC: Scheduled Caste, ST: Scheduled Tribe.

A 2008 government order instructed the IITs to employ 15%, 7.5% and 27% SC, ST and other backward caste (OBC) faculty, respectively–in line with the quota system being implemented for student admissions since 1973–at the entry-level post of assistant professor and lecturer in science and technology subjects and across all faculty posts in other subjects.

Almost a decade on, you can count the number of SC and ST faculty in the IITs on your fingers.

Dalit faculty made up no more than 1.12% of IIT faculty positions in December 2012, according to this statement made in the Lok Sabha (parliament’s lower house) that year: 0.12% of IIT faculty were tribals, while OBC faculty were 1.84%. The proportion of SCs and STs were 16.6% and 8.6% respectively, as per the 2011 census.

Source: Lok Sabha; *Based on the sanctioned strength of 5,706

As on June 2015, according to an answer received by a right-to-information request by a former student, quoted in this June 26, 2015, report in The Hindu, 2.42% of faculty in IIT Madras were SC or ST, based on faculty positions filled, while the similar figure for IIT Bombay was 0.34%.

This lack of SC/ST faculty could affect students from traditionally disadvantaged groups.

“Considerate and supportive faculty who are genuinely sympathetic to student’s problems are few,” said sociologist Virginius Xaxa, professor of eminence, Tezpur University, who has studied the adverse attitude–as this commentary details–towards SC/ST students in Delhi University.

“The pervasive attitude,” said Xaxa, “is that students coming through quotas are undeserving.”

Why do IITs lack SC/ST/OBC faculty?

Too few applicants: That is the overriding reason for not having enough SC/ST faculty, the directors of IIT Bombay, IIT Kanpur and IIT Madras told IndiaSpend.

“We have very few scheduled caste faculty because we receive too few applicants from this category,” said IIT Bombay’s Khakhar.

“We receive too few good-quality applications from SC/ST candidates who meet the minimum threshold for an IIT faculty,” said Indranil Manna, director, IIT Kanpur. “While we are committed to the law and our social obligation, we are also keen to protect the IIT brand, a globally recognised Indian brand that has taken fifty years to build.”

Could prejudice impede the employment of faculty from disadvantaged communities?

In August 2016, the Madras High Court concluded that IIT Madras had committed “gross irregularity” in passing over associate professor WB Vasantha–a faculty member from a backward caste–for promotion in 1995, and then again in 1997, for lesser-qualified candidates.

“There is no corner of India where prejudice against dalits doesn’t exist,” said Anand Teltumbde, senior professor, Goa Institute of Management, formerly with IIT Kharagpur.

“It took the public sector many years to overcome resistance to employ dalits at managerial levels,” said Teltumbde, the grandson of BR Ambedkar, the writer of India’s Constitution. “India has reconciled itself to admitting dalit students in the IITs, but resistance to admitting dalit faculty is still very strong, a dalit must expect to fight the system.”

Some IITs are bending rules to increase SC/ST faculty, others do nothing

Some of the IITs that IndiaSpend contacted for comments have started to bend the rules to increase the number of SC/ST faculty. Some are doing nothing.

“We have not taken any specific measures to increase the number of faculty members belonging to the scheduled castes,” said Khakhar.

Almost all the SC/ST faculty on the rolls of IIT Delhi today were hired a couple of years ago during a special recruitment drive, a senior faculty member, requesting anonymity given the sensitivity of the topic, told IndiaSpend.

IIT Madras has considered conducting a special recruitment drive for SC/ST faculty, over and above its six-monthly recruitment cycle. However, “so far, a special drive does not seem like an idea that will give us more candidates as we are constantly on the lookout for SC/ST candidates during regular recruitment”, said Bhaskar Ramamurthi, director, IIT Madras.

IIT Kanpur’s Manna sees rolling advertisement on the website as a better option to recruit SC/ST faculty than a separate, one-time recruitment drive. “A drive would only provide access to talent existing at a given point of time,” he said.

SC/ST applicants compete against general category applicants in regular recruitment. Does that increase the odds against them? .

Manna does not think so: “SC/ST candidates would not be disadvantaged because they are treated under a separate category with a different level of expectation,” he said.

At the entry level, applicants need not possess “a superlative record”, said Manna. A doctoral degree from a “decent” university, a good academic background, some good publications and a couple of years of work experience.

“I would definitely prefer the SC/ST candidate if I had three candidates of different social status but comparable merit and qualification,” said Manna, who added that IIT Kanpur would only relax the work-experience requirement for an “exceptional” SC/ST doctoral candidate and “appoint such a candidate on a contractual basis with scope for regularisation in due course”.

“We relax the age and work experience norms for OBC/SC/ST candidates to ensure more candidates from among those who apply are called for interview,” said IIT Madras’s Ramamurthi. “We also ensure representation from reserved categories in the selection committee when we have OBC/SC/ST applicants. They make allowance for skills which can be picked up with experience.”

Improve the learning environment, offer training to increase SC/ST faculty

At a December 13, 2016, meeting of directors of the Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs)–India’s chain of prestigious management institutions, where too the government has urged faculty quotas–to discuss ways to increase faculty from traditionally disadvantaged communities, the IIM Kashipur representative described special fellow programme in management for SC/ST doctoral students, who will simultaneously be trained for faculty positions.

Asked whether he could consider absorbing his institute’s own fresh SC/ST/OBC doctorates as junior faculty, Manna said: “The IITs follow a strict policy on preventing inbreeding. We would prefer that our doctorates work away for a few years, then return to us if they are interested.”

Instead, he suggested that the government take on the training of SC/ST doctorates with potential, with the intention of bringing them up to the IIT standard.

“It isn’t enough to legislate and require IITs to employ a certain number of SC/ST faculty,” he said. “Surely a group of 100 SC/ST entry-level faculties can be created to start with?”

IIT Madras has relaxed the prevention-of-inbreeding condition for SC/ST doctoral scholars. “But like our PhD scholars from the general category, our graduating SC/ST scholars often join other centrally funded technical institutes, national laboratories, industry, foreign universities, etc.,” said Ramamurthi.

Improving the learning environment and training potential candidates in-house would likely help retain more SC/ST doctoral scholars.

“Students aware of the environment in the IITs may be reluctant to join as faculty,” said Tezpur University’s Xaxa “Academic progress depends greatly on how comfortable you feel in an environment.” Aniket, clearly, did not.

(Bahri is a freelance writer and editor based in Mount Abu, Rajasthan.)

Courtesy: India Spend