“The NTA claims that the lack of a localized increase in toppers at specific exam centres is evidence against widespread malpractice in the exam. However, this argument is flawed. If malpractice is widespread and affects most exam centres, localized analysis will fail to detect anomalies because the issue is systemic. The NTA is not attempting to investigate potential systemic malpractice that could impact the entire exam. Instead, they are using the absence of localized malpractice using absence of localized inflation to argue against widespread malpractice. This approach ignores the possibility that mark inflation and other irregularities could be occurring uniformly across all centres, indicating a systemic rather than localized issue.”

During the last hearing concerning the irregularities in the National Eligibility cum Entrance Test – Undergraduate (NEET-UG) 2024 on July 8, the Supreme Court had directed the union government and the National Testing Agency (NTA) to assess the extent of the damages caused by the exam paper leak/breach. Additionally, the court instructed the NTA to identify if the beneficiaries of the breach could be distinguished from the honest candidates. Just two days later, on July 10, the NTA and the Ministry of Education (MoE) filed affidavits in the Supreme Court, which included an analysis report signed by IIT Madras.

The union government’s decision to assign the analysis task to IIT Madras has sparked allegations of quid pro quo. Critics suspect that the institute might be repaying a favour to the government following the mishap during the JEE (Advanced) in 2017. This choice also raises questions about potential anomalies and conflict of interest, as IIT Madras, being the organizing institute for JEE (Advanced) 2024, was a member of the governing body of NTA. Such concerns cast doubt on the objectivity and impartiality of the reports produced by IIT Madras for the government and NTA.

It must be noted that in the report by IIT Madras, submitted along with the affidavit by MoE clearly mentions that the analysis was not conducted by an IIT Madras team by themselves, rather, the analysis was performed by the NTA team which was only verified by the IIT Madras team. This is significant because this allows for NTA to cherry pick parameters and representations of the data in order to downplay the possibilities of widespread malpractices which would tarnish its reputation.

Moreover, in the IIT Madras report, it is mentioned that Python was used for data processing, PostgreSQL for data storage, and Metabase for analysis. However, the report fails to explain the methodology or the logic behind the selection of each parameter used in their analysis. There is no detailed explanation of the criteria or the reasoning for choosing specific parameters to represent in the report, nor how these parameters would effectively indicate whether there is widespread or localized malpractice. This lack of transparency in their methodology raises doubts about the validity of their conclusions regarding the integrity of the exam process.

Affidavit by Ministry of Education

The report states that the marks distribution follows a bell-shaped curve, indicating no abnormality. The NTA reasons that, given there are only 1.1 lakh seats, they analysed the data of the top 1.4 lakh students. However, half of these seats are in private colleges where any qualified candidate (more than 12 lakh in total) can secure admission with sufficient funds. Therefore, individuals aiming merely to qualify for NEET might also engage in malpractice, and they could fall anywhere within the rank ranges up to around 12 lakhs. The assumption that malpractices occurred exclusively within the top 5% or that everyone who engaged in malpractice ended up in the top 5% is unfounded. In fact, data (Annexure A1, page 21-23 of NTA affidavit) from Bihar reveals that candidates who obtained the question paper before the exam scored different marks, many of which are not within the top 1.4 lakh range. Consequently, it is not possible to determine if malpractice occurred by merely examining the curve. If the candidates who engaged in malpractices scored varying marks, and rise in marks due to malpractice is evenly distributed across different ranges, that would still produce a bell curve. Hence, the current analysis fails to account for the potential widespread nature of malpractice.

The NTA claims that the lack of a localized increase in toppers at specific exam centres is evidence against widespread malpractice in the exam. However, this argument is flawed. If malpractice is widespread and affects most exam centres, localized analysis will fail to detect anomalies because the issue is systemic. The NTA is not attempting to investigate potential systemic malpractice that could impact the entire exam. Instead, they are using the absence of localized malpractice using absence of localized inflation to argue against widespread malpractice. This approach ignores the possibility that mark inflation and other irregularities could be occurring uniformly across all centres, indicating a systemic rather than localized issue.

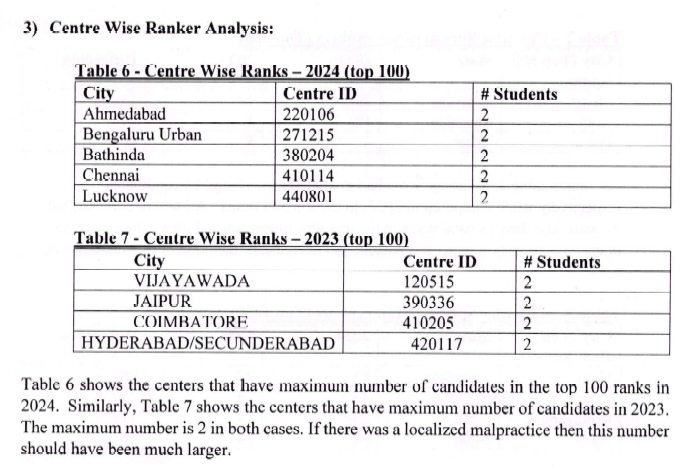

Tables 6 and 7 in the report present centre-wise rank lists, highlighting the centres with the maximum toppers. Table 6 shows data for 2024, while Table 7 shows data for 2023. They compare data of different centres from two different years and focus on the fact that in both cases, only two students from each centre made it to the top 100 ranks. They use this as an argument to deny localized malpractice, claiming that “if there was localized malpractice, then this number would have been much larger.” This is a baseless assertion because localized malpractice could also result in an increase in the number of people who qualified or achieved higher ranks than they would have without malpractice, and not necessarily only in the top ranks. The assumption that anyone engaging in malpractice would end up in the top rank list is flawed.

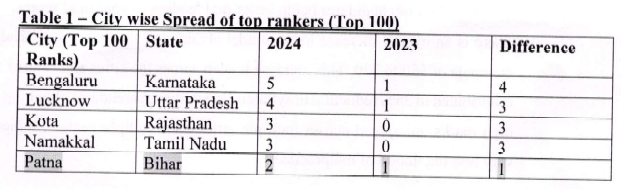

Here, the report emphasizes that this year there are only two students from each centre in the top 100, just as there were last year, indicating no localized malpractice. It is to be observed that here, where there is no increase in the number of toppers, they present it is evidence for lack of localized malpractice. However, in the case of an increase in the number of toppers, instead of investigating the possibility of a malpractice, they simply downplay the significance of the increase and move on. For example, in Table 1, the number candidates from Bengaluru to reach top 100 ranks increased from 1 in 2023 to 5 in 2024, which is a staggering 400% increase in Bengaluru alone. However, the NTA merely commented that this was the maximum increase seen in this category downplaying its significance and moved on to claim that this data does not indicate abnormality instead of investigating this significant increase in the number of toppers there. This raises doubts on the consistency of metrics used by the NTA to indicate malpractices.

It is unclear what magnitude of increase or decrease in the number of toppers in which category is deemed normal and how NTA and IIT Madras arrived at these standards. Importantly, when implying that the increase from 2023 to 2024 is not abnormal, it is essential to compare this with the increase from 2022 to 2023 and the previous years. However, IIT Madras did not consider the data of toppers from NEET 2022 in these tables. Without this comparison, the qualitative claim of the increase being normal enough to dismiss the possibility of malpractice is unsubstantiated.

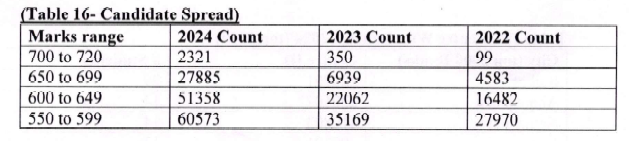

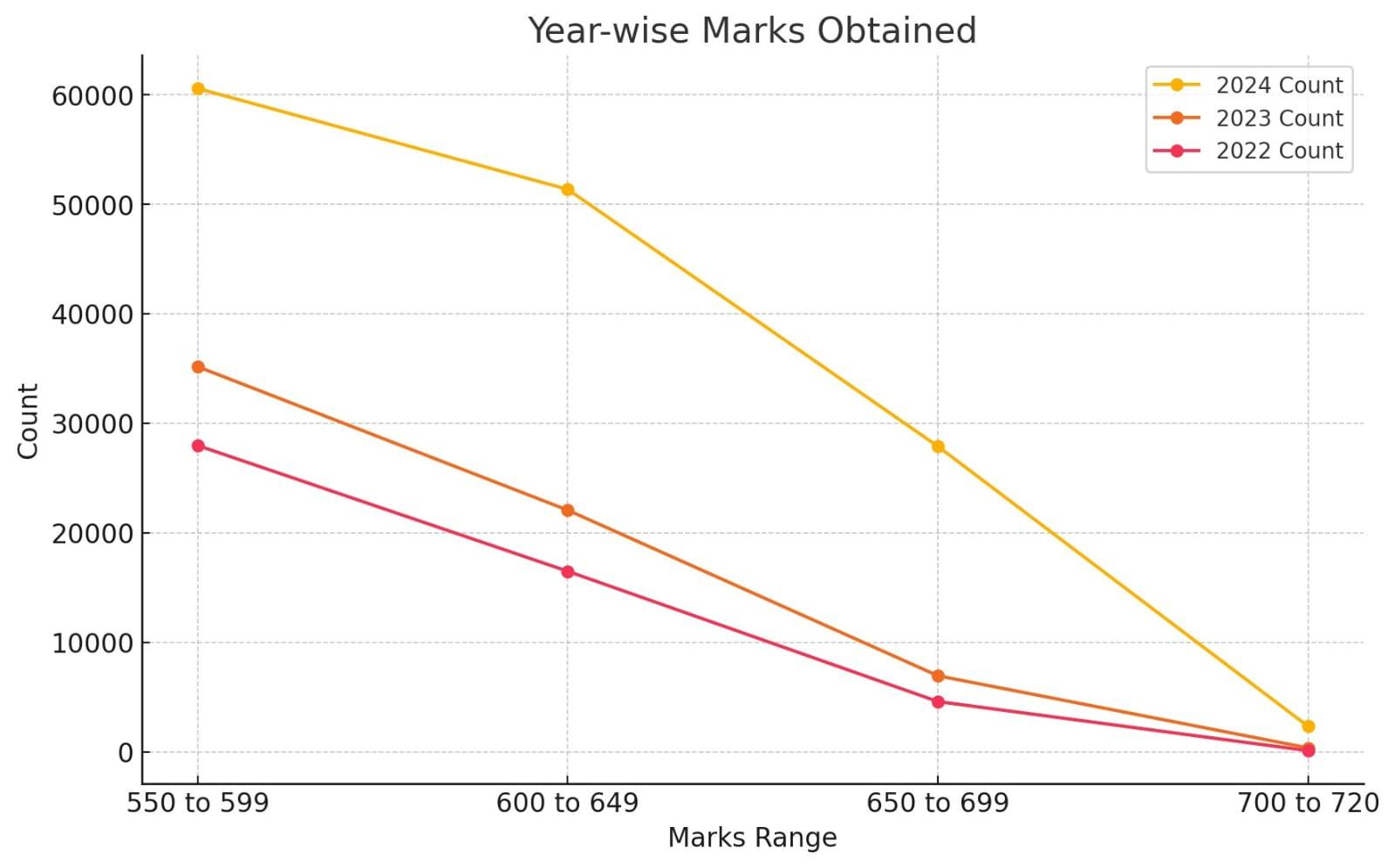

Plotting the data in table 16, which is the only table in which data from 2022 is included, it is clearly seen that there is a huge abnormal mark inflation in 2024. In the report, NTA maintains that the increase in the number of toppers in individual centres and cities is not inexplicably abnormal. This logically suggests that more centres contributed to toppers in 2024 compared to 2023. There should also be a significant increase in the number of centres producing toppers in 2024 that never had toppers in previous years. As mentioned above, NTA had dismissed localized malpractice citing the lack of increase in toppers across years. If we follow the NTA’s logic that an increasing number of students from certain centres can indicate alleged malpractice, then the NTA should actually scrutinize data on centres or cities that never had toppers in previous years but suddenly have toppers in 2024. According to their own logic, this would be a better metric to identify potential centres where malpractice could have occurred. However, they do not provide this data. Instead, they are cherry-picking data that suggests consistency between this year and previous years, thereby claiming that there is no malpractice.

Moreover, NTA simply attributes this increase in the marks obtained by students to 25% reduction in syllabus. However, this analysis cannot determine whether the inflation is due to the syllabus reduction, a decrease in exam difficulty, or malpractice. The NTA’s justification that a 25% syllabus reduction caused this significant mark inflation is unfounded and appears to be a misleading explanation, which IIT Madras has unfortunately endorsed.

There are two primary issues: mark inflation and malpractices. While this document is ostensibly commissioned to investigate malpractices, it tacitly downplays the mark inflation that has occurred, dismissing it as normal and simply attributing it to the increase in the number of candidates and the reduction in the syllabus.

Affidavit by NTA

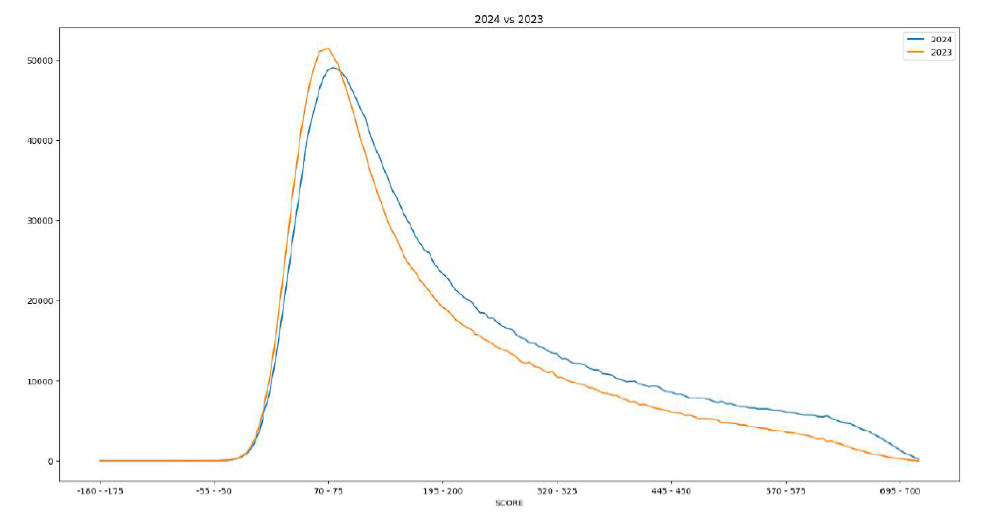

The following graph indicates a significant increase in the number of students scoring higher marks in 2024 compared to 2023. This is evident from the higher tail extending towards higher scores.

NTA has only considered the data for the years 2023 and 2024 and claims that the increase in the number of toppers from 2023 to 2024 is “not significantly higher in number” than previous years. When claiming that the increase in number of toppers from 2023 to 2024 is not significant, it is essential to contextualise this claim historically with data of number of toppers from previous years, which the NTA has conveniently not done.

NTA explains that out of the 67 candidates who initially scored full marks, 6 of them got that score because of grace marks, which was later redacted and a retest was held for those candidates. As none of them scored 720 in the retest, the number of toppers is now 61. Further, it states that, out of the 61, 44 candidates went from scoring 715 to 720, on account of the revision of answer key, and hence the “actual” candidates with full marks are only 17.

Forty-four candidates ended up getting full marks after selecting an answer which is accepted as correct according to the NTA, causing a revision in the answer key. However, NTA, weaponising its own fault of providing two correct options to a question, is trying to create a false difference between “actual” toppers and other toppers, to downplay the mark inflation this year as evident with 61 toppers with full marks.

Moreover, the report attributes the increase in number of high scorers to 25% reduction in syllabus. This argument of NTA must be justified by demonstrating that students across different percentiles—those at the bottom, middle, and top sections of the performance curve—are scoring higher. If the exam is indeed easier due to the reduced syllabus, this ease should be reflected uniformly across all performance levels, resulting in a noticeable shift of the entire distribution towards higher scores. However, an examination of the data curve reveals that this is not the case. The lower end of the distribution shows little to no change in candidate performance, while there is a significant increase in marks among the top performers. Particularly, the number of students achieving very high scores has risen markedly compared to previous years.

Further, to claim that the exam was easier due to the reduction of the syllabus, the NTA in their affidavit (page 19) states that because the syllabus was reduced and the time remained the same, the question paper was much more “balanced”. However, despite the reduction in the syllabus, the number of questions students had to answer remained unchanged, and the time allotted was the same as in previous years. Hence, the NTA’s framing in the affidavit which suggests that the exam became easier due to more time, is misleading.

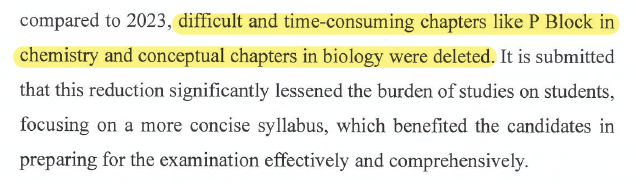

The NTA claims that “difficult and time-consuming chapters like P Block in chemistry and conceptual chapters in biology were deleted.” This statement reflects a strategic wordplay. They characterize chapters like p-Block, from which questions are often memory-based making them easier to attempt, as “difficult and time-consuming,” while characterizing unspecified chapters in biology as “conceptual,” implying that they were difficult as well. This renders the narrative that the exam was much easier due to syllabus reduction. Notably, the affidavit does not mention the physics syllabus reduction, wherein many of the subtopics that were removed still continues to be relevant for a comprehensive conceptual understanding of the chapters they were a part of. For instance, the fundamental concepts of average speed and average velocity are the subtopics “cut down” in the Class 11 Physics chapter introducing Kinematics. Moreover, many of the subtopics removed historically did not carry as much weightage in NEET. These considerations challenge the claim that the syllabus reduction made the exam significantly easier.

The NTA states that the syllabus reduction made the paper “balanced, ensuring accessibility for students from diverse backgrounds,” implying that the easier question paper enabled better performance from these students. This assertion raises significant concerns about the nature, intent, and attitude of NEET towards marginalized students in general. By claiming that reducing the syllabus and burden has helped marginalized students, the NTA implicitly admits that NEET has been unduly burdensome for these students in previous years.

Additionally, the NTA claims that the 2024 NEET-UG question paper was made easier to provide students from various geographical and socio-economic backgrounds an equal opportunity to succeed. They argue that this move was intended to discourage the growing dependency on coaching institutions. The NTA must substantiate its claim by providing information on the steps consciously taken to reduce the burden on marginalized students, and how this was reflected in the question paper. Further, it is important to analyse the data showing the proportion of students from marginalized backgrounds who secured admission into government colleges (ranks above 50,000) in 2024 compared to the previous years to assess the impact of these steps.

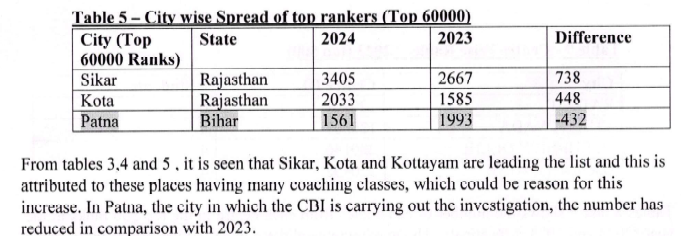

However, this claim is contradicted by NTA’s data showing that most of the top 60,000 rankers, who qualify for government medical seats, come from cities with extensive coaching facilities. In the report, IIT Madras argues that cities like Sikar, Kota, and Kottayam lead in the number of toppers within the top 1000 ranks due to “these places having many coaching classes”. The report inadvertently acts as an advertisement for coaching centres. Strikingly, when the NTA presents that the top cities producing the highest number of NEET rankers are those with many coaching classes, the NTA is essentially admitting that the ability to access and afford coaching classes is crucial for cracking NEET and achieving top ranks. This highlights a systemic bias within the NEET system that favours wealthier candidates and undermines the claim of improved accessibility for marginalized students.

The data analysis conducted by the NTA only examined whether students in these centres secured enough marks for “admission to medical colleges of primary importance,” which in our understanding refers to government colleges. This raises a doubt as to why NTA does not seem to deem worthy of consideration the possibility of students seeking to gain admission to private colleges engaging in malpractices. NEET initially promised to curb the exorbitant fees of private medical colleges, a promise yet to be fulfilled. The 50th percentile cut-off to clear NEET ensures that individuals who can afford such high fees can surpass those with higher marks and still become doctors. While NEET was supposed to champion merit, it has failed to address the commercialization of medical education, which benefits the wealthy over those with higher scores. Now, even in their analysis of NEET malpractice, the NTA’s approach seems to exclude the wealthy from their scrutiny.

Instances of malpractices

The case of malpractice in Godhra (page 34-36) highlights significant vulnerabilities in the NEET examination process. In Godhra, the deputy superintendent of examination conspired with students to manipulate OMR sheets. The deputy superintendent in this case was a school teacher at the examination centre who was responsible for sealing and returning the OMR sheets to the NTA and had the opportunity to fill in correct answers on blank OMR sheets left by the candidates (page 82-83). His involvement underscores how internal personnel can subvert security protocols despite the NTA’s measures to prevent malpractices.

The only reason the incident in Godhra came to light is because district officials discovered the plan and acted in advance to foil it. The Godhra case reveals a significant gap in the NTA’s oversight and security measures, suggesting that undetected malpractices could be happening elsewhere across the country without the knowledge of local authorities. This uncertainty further undermines the credibility of the NTA’s claims regarding the sanctity and integrity of the examination process.

The Godhra incident reveals systemic issues within the NTA’s protocols demonstrating that the perpetrators can be among the entrusted personnel. If malpractices occur at such systemic scales, then the current analysis by the NTA and IIT Madras, which is based on the assumption that malpractice can only occur through individual students cheating, will not be able to detect them. The analysis does not consider the issue of internal corruption within the system itself. There is an imperative need for mechanisms to be in place to protect the integrity of the exam from internal manipulation at administrative levels.

Moreover, the NTA’s affidavit mentions a paper leak in Patna, where individuals obtained the question paper before the exam. However, in the affidavit, it has not been explained how the question paper was leaked despite stringent security protocols, raising doubts about the effectiveness of NTA’s security measures. In the Patna case, it is crucial to note that the NTA still does not know how the question paper was leaked, as the matter is still under CBI investigation. Without understanding how this particular leak happened and determining whether similar leaks occurred elsewhere, the NTA cannot confidently claim that issues at these centres does not have “wide spread ramifications of impactable magnitude.” Without identifying and addressing the root cause of the leak, it is impossible to evaluate whether the exam process has suffered systemic failure or not.

In the last hearing, the Honourable Chief Justice of India asked whether the timing of the leaked question paper in Patna allowed enough time for it to spread across the country or if it was limited to a case of localized malpractice. In response, the NTA’s affidavit failed to address this crucial question. Evidence showed that candidates were tutored with the leaked question paper and provided with solutions, indicating that there was sufficient time to generate the answers, teach the students, and prepare them for the exam. However, the affidavit does not mention any of these instances or details. It also omits how the question paper was transferred to those generating the solutions, whether through electronic means or otherwise. This lack of information leaves significant gaps in understanding the extent and mechanics of the malpractice, further questioning the integrity of the examination process.

The way ahead

On page 74 of the affidavit, the NTA shames candidates who went to court for a re-examination, arguing that their scores are too low and insinuating that their motivation for calling for a reexam is to get another attempt. This begs the question who are the ‘right’ petitioners in the eyes of the NTA? Candidates who already scored high marks are unlikely to want the current exam scrapped, as they stand to gain from their existing scores. Only those who did not score highly would ask for a re-exam, as they are the ones most affected by any widespread malpractice. The NTA’s stance effectively silences any opposition or calls for a re-exam by dismissing petitioners based on their performance. This is a contrived way for the NTA to avoid accountability. The call for a re-NEET is about the NTA’s performance in terms of transparency and fairness as an examination conducting authority, and not about the petitioners’ performance. It is essential to focus on the integrity of the examination process rather than discrediting those who raise legitimate concerns.

Finally, students have been put through a lot already due to the stress caused by NEET this year and its failings. We request the NTA to not further exacerbate the misery of the students and their families by selectively choosing and presenting data and silencing student concerns. We demand that the NTA be transparent and make its data public for social audit so that we as a society can assist students in finding the truth and some long overdue relief.