Kamla Devi (not her real name), of advanced but uncertain age, lives in Lohari, a remote adivasi village located inside a wildlife sanctuary in Udaipur, Rajasthan. On a summer day in 2016, we approached her as she was chasing after a small herd of goats, to ask questions as part of a study on the relation between ageing, paid work and pensions.

An elderly farmer delivering grain at a paddy procurement centre near Raipur, Chhattisgarh. Over a third of India’s elderly people–38%–continue to work, according to the National Sample Survey Office.

Our very first question–whether she was a beneficiary of the government’s non-contributory pension scheme for the aged–irritated her. She explained that she was indeed a beneficiary but did not want to be one. Local officials had refused to give her work under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA, the law that governs the key central government employment guarantee programme) since she received Rs 500 a month as pension under the scheme.

In a clear violation of MGNREGA, Kamla Devi was informed that the pension was the reason she had been denied work under MGNREGA. She was clear that she wanted to continue working to earn a living, not just because the pension is too little, but, as she explained, because she was still capable of labouring.

In the block headquarters of Kotda in Udaipur district, the study took us to Irfan’s house (he uses one name). He put his age at close to 60 years and said he had spent the better part of his life transporting loads on his head for a fee. Having remarried in his old age, Irfan lived with his young wife and 10-year-old son. He said he suffered from severe back pain and muscle soreness, and would like nothing more than to stop working. However, between his son’s school fees and his own medical bills, he had no choice but to work. Recently, his wife had also begun to look for work to share his burden.

In Rajasthan, women aged 55 years and above and men aged 58 years and above receive a monthly pension of Rs 500 as part of the Centre-led non-contributory social pension scheme, the Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension Scheme. The central government contributes Rs 200 for those aged 60 and above and Rs 500 for those aged 80 and above and falling below the poverty line. The Rajasthan state government has achieved near universal coverage under this scheme, entitling a minimum of Rs 500 per month to each beneficiary. However, the amount is so grossly inadequate–at just over Rs 16 a day, it would not buy half a litre of milk–that it leaves the elderly who have no other financial resources with no real choice but to work for a living. Yet, whether they find work is subject to lingering prejudices, as in Devi’s case.

No income and social security

Governments across the world provide pensions for varying reasons. However, the shared logic behind old age pension is to enable those beyond a certain age to maintain a reasonable standard of living without having to engage in paid labour. In India, this is empirically true for people who receive assured monthly pensions following their retirement from work, but, in the non-formal sector, people do not retire from work at any stipulated age.

The participation of the elderly in the workforce is all pervasive, particularly in the unorganised sector that employs the majority of Indians, without formal conditions of employment.

According to the 68th round of the employment-unemployment survey 2011-12 conducted by the National Sample Survey Office, over a third of India’s elderly people–38%–continue to work. Extrapolating from the Census 2011 figure of 103 million elderly people in the country would put the number of elderly people who continue to remain in paid employment at 39 million.

The New Delhi-based Centre for Equity Studies (CES) conducted a study–unpublished as yet–in seven locations across rural and urban Rajasthan from August to October 2016, in which trained field investigators interviewed 791 people above the age of 55 years to understand people’s experience of ageing without income security. Of the total sample of 791 respondents, 57% were women and 43% men; 59% reported to be engaged in at least one remunerative job. Field investigators approached every elderly person (above the age of 55 years) in every house in a given location. Those who met Rajasthan’s exclusion criteria for state old age pensions–by receiving a job-related pension and/or being an income tax payee–answered fewer and truncated questions, but their numbers were quite limited (16 individuals).

A key finding of the study was that, in the absence of adequate income and social security, the elderly lack real choice in determining the extent, duration and nature of their engagement with paid work.

Little choice but to work

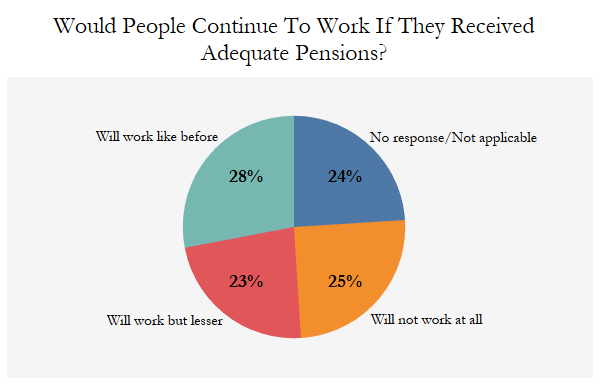

The survey asked one question to all respondents:

“Assuming a situation wherein you receive an adequate pension to sustain yourself, would you:

1. Work as much as before (before receiving adequate pensions) 2. Continue work but less 3. Not work at all.”

Source: Centre for Equity Studies; N=791

The elderly respondents varied vastly in how they viewed their engagement with work: Over a fourth said they would continue to work as before if given an adequate pension, but nearly half said they would work less (23%) or not work at all (25%).

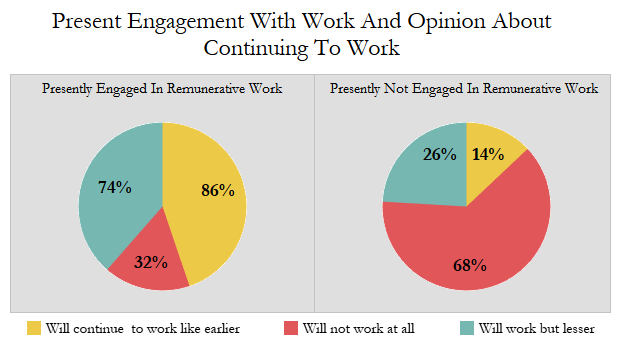

Of those who said they would continue to work as before, 86% said they were currently engaged in work. In contrast, 32% of those who said they would not work said they were currently engaged in regular remunerative work.

Source: Centre for Equity Studies; P Value: 0.00, N=599

How much would an adequate pension be? Another survey question asked respondents to state a monetary amount that would cover their basic needs. The average amount cited was Rs 1,875–more than three times the monthly pension at present–while the median value was Rs 1,500, three times the current monthly pension.

Adequacy is a concept that cannot be defined in monetary terms alone, yet even in purely monetary terms, people understood adequacy of pension differently. Those respondents who said they would continue working as in the past put the average value of an “adequate” pension at Rs 1,600–over three times the existing old age pension–while those who said they wished to work less or not at all put the amount at Rs 2,000–which is four times the pension given. Clearly, they saw adequacy in relation to their own capacity to work and supplement their pension, as opposed to their age in and of itself.

At the same time, even the highest of the amounts cited as adequate, Rs 2,000 per month, amounts to less than half the existing minimum wage and less than a fourth of the national per capita income.

Gender affects perceptions

There was a stark difference in the responses of male and female respondents to the question whether they would continue to work but in a reduced capacity if given an adequate pension. A greater proportion of the male respondents (36%) looked forward to negotiating the volume of work, as compared with female respondents (26%). However, an equal proportion of men and women–a little over one-third–said they would continue to work irrespective of the pension. This suggests that other considerations aside, women found it difficult to

Table 3

conceive of a scenario where they would be able to negotiate lesser work than their current work burden.

More women (36%) than men (28%) said they would not work at all.

Source: Centre for Equity Studies; P Value: 0.01, N=599

Elderly men are proportionally more likely to work less when given an adequate pension as compared with women, more of whom would rather not do any paid work at all.

India has generally low participation of women in paid work–at present about 25%, according to the International Labour Organisation. It is even lower for women above the age of 60 years, according to a 2016 report, by A. Bheemeshwar Reddy in the International Journal of Social Economics, which argues this could be because women’s relationship with paid work itself is far more complex compared with men’s. Because of the pervasive gender-based division of labour, women perform tasks across the spectrum–contributing to remunerative chores at the workplace, often for a lower monetary value than men’s work, and to non-remunerative chores at home.

Hence, in this study, it is difficult to understand what women mean when they say they will not work at all, CES found. For women, whose labour is unrecognised in multiple ways, often by themselves, retirement is a misleading concept.

Pension, the key enabler

Without adequate pension, it is impossible to imagine a scenario in which the elderly poor can choose whether to work or not. To ensure a dignified standard of living for the elderly, timely and sufficient pensions are imperative.

This choice of working or not has always existed for those who receive assured pensions after retiring from their jobs. This choice must be extended to all older people.

Notes:

- The study was conducted in Rajasthan in partnership with Astha Sansthan, UNNATI and Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan, Rajasthan. A more detailed discussion on old age pensions can be found in the “India Exclusion Report 2016” due to be released in May 2017 by CES and Yoda Press.

- Kamla Devi’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

Update: The story was updated to reflect that the number of elderly Indians who continue to work, when extrapolated from the representative NSSO survey, is 39 million.

(Sampat is a Delhi-based researcher. Dey is a researcher with the Centre for Equity Studies, New Delhi.)

Courtesy: India Spend