India’s general elections kicked off on May 11 and run until May 19, with the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party facing off against the main opposition force, the Indian National Congress. One of the main issues opposing the two are charges of “crony capitalism” against Prime Minister Narendra Modi, as epitomised by the ongoing “Rafale scam”.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi (C) waves from the stage during a traders national convention in New Delhi on April 19, 2019. Money SHARMA / AFP

Modi has been accused of favouritism toward his friend and political ally Anil Ambani, a multi-millionaire at the head of Reliance, a 1.7 billion dollar firm. In 2015, Ambani formed Reliance Defence Limited, which bypassed the mandated procedures to obtain a deal with French defence company Dassault for the sale of 36 Rafale fighters for 8 billion euros. Ambani’s company won the contract over the government-owned HAL and the deal reportedly pushed up the price of the aircraft by more than 40%. Yet Ambani’s firm was not a defence specialist.

Billionaires in politics

Such examples of intertwined relationships between government and business figures in India are so frequent that a book by Financial Times journalist James Crabtree, The billionaire raj: A journey through India’s new gilded age, has become a bestseller.

In 2002 (the latest year for which figures are available) 30 of the 245 members of the upper house (the Rajya Sabha) were from business.

This involvement of business directly in politics is common. In France, 21 senators are listed as being heads of enterprises. In the United States, two notable if very different examples are the current president, Donald Trump, and the former mayor of New York (2001-2013), Michael Bloomberg.

As pointed out by Paul A. Baran of Stanford and Paul M. Sweezy of Harvard, it is rare for politicians to be open with voters about their business dealings.

Does business mean development?

Most such politicians describe their approach as “business friendly” or connections as “progress”, which in Hindi is translated as vikas. The word has been at the heart of Narendra Modi’s campaign since 2014.

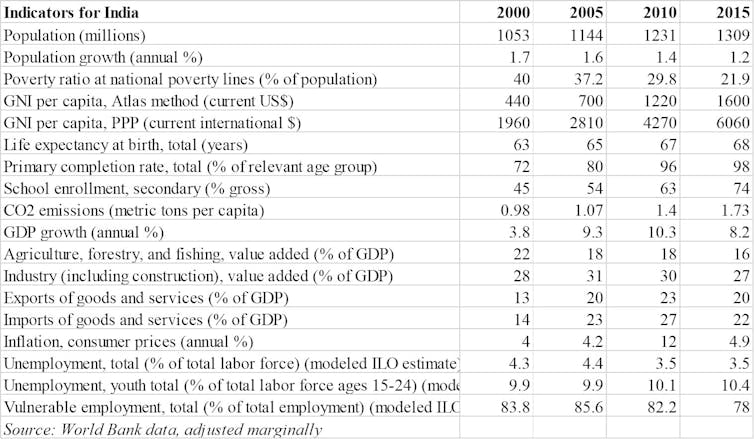

Yet the country faces serious economic and development issues. The table below is based on selected indicators from World Bank and other sources, and is important for understanding the background to the statistics being bandied. For example, when inflation was running at above 10% during 2009-2012, it was a serious election issue, but today it is not because inflation is down to 5%.

A selection of indicators from the World Bank and other sources. When data was not available, the last available figures are used. Poverty for the year 2000 is an estimate. World Bank, Author provided

Data indicate that in India poverty levels have fallen from 40% to 20%. But with a population of 1.4 billion people, the 20% figure means that 280 million of the country’s population is living in poverty – the combined total population of the biggest four or five European countries.

Certainly, India’s gross national income per capita has quadrupled, but has only tripled in purchasing power parity terms. This means that the currency is devalued against the US dollar and the real progress is significantly less. GDP growth rates have been as high as 10% in a few years, and given that the poverty ratio is reduced, part of this seems to have trickled down, as can be seen from the World Bank data. For example, almost all Indian villages have now been electrified, even though this may mean that only a small number of people actually have electricity.

An unequal access to progress

This unequal access to progress is disturbing, as indicated by India’s Gini coefficient, a measure of inequality. A Gini coefficient of 0 shows perfect equality, while 1 indicates maximal inequality. A recent OECD working paper shows that income inequality is higher in emerging economies – including India, where it is almost 0.5 – than those in developed countries.

The Gini coefficient is usually looked at in terms of income or wealth: Income is a “flow” concept of what one earns over a year, while wealth is a “stock” concept of the assets one owns at a point in time. The Gini coefficient of wealth inequalities are much higher than Gini coefficients of income inequalities even in the OECD – for example, the wealth Gini of France would be 0.70, and that of the United States and most Scandinavian countries would be over 0.80.

However, for emerging countries the data required to calculate these is not available and other proxies must be used. For example, Credit Suisse reports that wealth inequality in India is second only to Russia: the top 1% and the top 10% control more than 50% and 70%, respectively, of the country’s wealth.

Decline of the industrial world

One of the reasons for such disparities is the tendency of capitalism to limit wages and increase profits. This is enhanced by mergers and acquisitions that increase monopoly power. This in turn leads to the rise of the “happy few” who concentrate and aggregate wealth, stock options and companies. However, there is a limit to what these few people can consume. As a result, aggregate demand falls, limiting growth and pushing into poverty greater numbers of those who need to consume but do not have the purchasing power. They in term search the cheapest solution, which is often to purchase Chinese-made goods.

In China, growth is fuelled by global demand, economies of scale and high productivity of its workers. In India, however, the share of industry seems to be rapidly declining, unable to compete with imports. Some observers such as Dani Rodrik, Amrit Amirapu and Arvind Subramanian consider that it is unlikely that industrialisation will return to India and that the country still relies heavily on its software services.

In April 2019, India’s Jet Airways announced it would declare bankruptcy. Here, employees of the carrier in Kolkata hold placards at a rally to save their jobs on April 24. Dibyangshu Sarkar/AFP

The table above shows that the value added by agriculture and industry has reduced to 16% and 27% of GDP, respectively. However, these sectors still employ a lot of people, 43% and 24%, respectively. During the elections, the votes of farmers and industry workers remained important and politicians have to appeal to the two sectors, as much as to services, whose share has grown to 33% of the occupational structure.

The working class in India are no longer the traditional voters of the waning communist parties which now rule only in the southern most Kerala State. The other major state is West Bengal, where the working class brought them to power two decades ago but have now changed their support to the regional party, Trinamool Congress, headed by Mamata Banerjee.

This partly explains why the farmers remain the core of support for several political parties. For example, the Congress Party has promised a farm loan waiver. During the ongoing elections it has also pushed its “Nyuntam Aay Yojanan” (NYAY) scheme, which would assure minimum income to all farmers.

Day-to-day development left out

Many in India feel that the basic infrastructure has improved, the digital divide remains a major problem for those who do not have electricity to charge phones or get Internet.

Primary education has taken a great leap forward, but secondary education has still a long way to go. Nevertheless, the secondary enrolment rate has increased by over 60% in the 15-year period reported from 45% to 74%. The life expectancy has increased very little – 68 years in India compared to 80 in developed countries, indicating that public and private investments in health have not kept up.

At the same time, pollution has doubled since 2000, as indicated by the CO2 emissions. According to a recent statement by Greenpeace 22 of the world’s most polluted cities are in India.

An Indian farmer walks as he burns straw stubble on his field on the outskirts of Faridabad, in the northern Indian state of Haryana (April 18, 2019). Money Sharma/AFP

Unemployed youth, a demographic time bomb

Unemployment today in India is only 6.7%, considerably below that of France and many developed countries, but 80% of the jobs are vulnerable or within the informal sector. This represents a demographic time bomb, as most of those who fall victim to unemployment are men and women between 15 and 24 years. As indicated in the table, their unemployment rate in 2015 was 10.4%, almost three times the overall figure of 3.5%.

The impact of youth unemployment is particularly severe, as recent studies have demonstrated that it can create or increase substance-abuse issues and mental problems.

But with India’s GDP growing at 8% per year, the impact on politics has been considerable. Many Indian voters seem willing for the moment to overlook the everyday struggles they may face, hoping that the trickle-down effect of a “business friendly” government will help the overall economy.

Courtesy: The Conversation