India is run by an elected dictatorship fuelled by Hindu fundamentalism which the Union and other cognate state governments support with fervour through tough menacing laws and policies sustained by the Union and politically cognate state governments.

The Enforcement Directorate and other agencies arbitrarily target those who are perceived as dissidents or political opponents in violation of the rule of law.

The not–so–silent aim is to convert India’s diversity into a pro- Hindu state. This affects our democracy, secularism, federalism and civil liberties.

I cannot speak with any authority of the ‘deep’ state which our distinguished chairman for this meeting, Mr [N.N.] Vohra knows about but may not disclose. It exists under the cloud of secrecy and confronts, even eliminates many in the name of national security. The deep state covers many deals, conspiracies and atrocities hidden from public exposure.

I was asked to celebrate the achievements of India’s constitution from 1950 over 75 years. Much can be written and said about this journey and many experiences can be drawn from it.

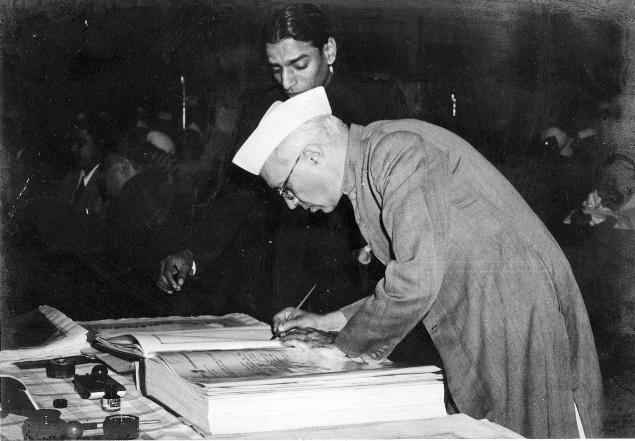

Nehru is much criticised these days, but his tenure should be remembered. He interacted with other non-Congress politicians, hostile journalists and those who opposed him.

When he spoke of the Seventh Fleet in a public statement, he was threatened with a privilege motion in parliament because in those days, all major matters had to be first placed on the floor of the house.

He confronted this with an apology. He faced a contempt motion in the Madras high court

with humility, was represented and won his case.

The infamous President’s Rule imposed in Kerala in 1959 during his tenure was at the instance of Indira Gandhi, then president of the Congress, and home minister Govind Ballabh Pant.

Nehru made mistakes, but our present controversies about him are political because the BJP and the Sangh parivar feel that by denigrating him, Modi’s status will be enhanced. Photo: Public domain.

I saw a picture in Justice Krishna Iyer’s house where Krishna Iyer, then a minister in the ill–fated government, was presenting a memorandum to a passive, even sad, Nehru. I asked Krishna Iyer to explain this photograph to me. The judge told me that he had informed Nehru that the Left coalition which had come to power and was threatened by President’s Rule was prepared to accept all of the Union’s demands. Nehru then told Krishna Iyer to speak to Indira.

Be that as if, may Nehru cannot escape responsibility for destroying the first elected communist government in the world. But to his credit, unlike now, he allowed a strong debate in parliament which took the government apart even if the Congress majority in parliament sustained the imposition of President’s Rule.

This episode also reflects on the need to separate political governance from constitutional decision– making. I will dwell no more on this. Those interested in my views on Nehru can read my long introduction to a book called Nehru and the Constitution (1992) where I invoke Milan Kundera’s evocative statement: “Metaphors are not to be trifled with. A single metaphor could lead to love.”

Nehru’s was a metaphor in India’s formative years and remains so and to be admired. He cracked down on powerful corrupt ministers and gave his all to democratic governance. Mistakes? Of course there were. Who doesn’t make them? Our present controversies about Nehru are political because the BJP and the Sangh parivar feel that by denigrating Nehru, Modi’s status will be enhanced.

There is academic controversy as well on Nehru’s economic policy, as seen in Arvind Panagariya’s The Nehru Development Model – History and its Lasting Impact (2024); and more generally by Tylor C. Sherman’s Nehru’s India – A History in Seven Myths (2022) and others. His photographs are being removed and replaced by Savarkar’s. But Aditya Mukherjee’s Nehru’s India – Past, Present & Future (2024) stands out at a time when history is being corrupted.

Mrs Gandhi did subvert the constitution in the sixties with uncalled President’s Rule against opposition– ruled states which came into power electorally after 1967. There was the dreaded Emergency (1975-77). But she was humbled by Indian democracy, the greatest gift by India’s constitution to her people.

Today we celebrate Modi, whose contribution to India’s democracy is winning elections through fundamentalism supported by crony capitalism, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and the Sangh parivar with ‘gifts’ to the poor – all in the name of growth and economic progress.

But I do not want to indulge in ungainly political dialogue or compare Modi’s rise to Hitler who also chose the path to power through democratic elections to the Reichstag to become chancellor. Nor am I interested in analysing his foreign policy as that of a flying salesman not just for India but himself.

Amidst speeches and oratory he has little time for governance; and has collapsed the distinction between governance and a constitutionally established state. My concern is less on the constitution’s journey over the past 75 years and more on the contemporary challenge to constitutionalism, whose basis is being challenged from within. The past informs the present which, in turn, informs the future.

II. Checks and balances

The challenges of our present discontents are characterised by the collapse of the system of checks and balances to discipline constitutional power. I believe that the principles of checks and balances are a visible and invisible basis for a successful democratic, secular and federal constitutionalism. Without this the constitution would sink into the abyss and give rise to promote an elected dictatorship established from within the constitutional framework.

I am not really concerned with the elected dictatorship in America, Turkey and other parts of the world, which are countries that have their own grievances, their own challenges and their own impossibilities. Trump raises important questions on India’s foreign policy and the global economy where India, for all Modi’s travels, is at sea. Trump summons. Modi responds. Weapons deals are made to bolster America’s military industry and war machine.

Let us see how this system of checks and balances works. The powerful executive is responsible to parliament. The judiciary is empowered to challenge any high– handedness by the executive or any authority of governance including parliament, to protect the liberties of the people, prevent religion from entering electoral politics and to defend a balanced federalism. It has overseen the conduct of the civil services and resolved their disputes and has taken on authoritarianism at different times, succumbing during the Emergency (1975-77).

Part of the checks and balances of the constitution protects the states in the hope that there will be cooperative federalism with equities. Unfortunately, we now have a coercive federalism which divides people, favouring these governments which side with Modi’s political

centre.

The Modi government supported by the RSS and other elements of the Sangh parivar has, in many ways, promoted a Hindu state. There is a 501– page report of Sanghi intellectuals to replace the present constitution with a Hindu constitution.

Is this really possible in India, which is the greatest experiment of governance over the most diverse multicultural, multi–linguistic and multi–religious nation– state, housing several civilisations?

India with its around 200 million Muslims, is demographically second to Indonesia along with Pakistan and Bangladesh. It dwarfs all Islamic countries of the Middle East. Its Christian population is greater than many states in the world. It houses Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains and many sects. People should realise that Hinduism is not a monolithic religion, but contains not only sects but religions within it. This is lost sight of by militant Hinduism and even the courts on which I am writing essays collected and titled Conquest by Law:

Essays on Colonising Hindu Religious Endowments and Religious Freedom in India.

What is also disturbing is the aggressive linguistic dominance of Hindi. India has many officially recognised languages. Hindi is the official language, English is to be used for the ‘official purposes’ but surely is now an Indian language. Hindi is to be progressively used officially and developed. (Articles 343- 351). But few lay people can comprehend Hindi’s propagation in its neologised Sanskrit form, especially in government notifications, which is alien.

Healthy checks and balances are needed so that all Indian cultures are articulated, expressed and nurtured in their own tongues. Photo: Harish Sharma/Pixabay.

But there lies the rub. The Eighth Schedule of the Constitution officially recognises 22 languages to include Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Kashmiri, Konkani, Malayalam, Manipuri, Marathi, Nepali, Oriya, Punjabi, Sanskrit, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu, Urdu, Bodo, Santhali, Maithili and Dogri. Of these languages, 14 were initially included in the original constitution. The Sindhi language was added in 1967. Three more languages, Konkani, Manipuri and Nepali, were included in 1992. Subsequently Bodo, Dogri, Maithili and Santhali were added in 2004.

These are the tip of the iceberg. The bewildering variety of Indian languages and their dialects can only amaze and define India’s diversity and linguistic federalism.

The Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) has been at the forefront to protect Tamil. The assertions of BJP leaders including Modi will not absolve the party and its cohorts for promoting Hindi nationalism even in symbolic titles of legislations, the text of which is otherwise in English. On my impromptu test with lay Hindi–speaking, relatively poor people, they do not understand the ‘Hindi’ words for programmes and legislation promoted for acceptance. Linguistic federalism has become an important issue. DMK leader M.K. Stalin has led the charge against imposing Hindi nationalism.

We need to go back to controversies in the constituent assembly where K.M. Munshi and N. Gopalaswami Ayyangar agreed to Hindi being an ‘official language’, and Article 351 gives the duty to the Union to promote the spread of Hindi. But, as H.M. Seervai and others pointed out, given the diversity of languages in India, Hindi cannot be the “national language”.

I argued the case of Uttar Pradesh Hindi Sahitya Sammelan v. State of U.P., (2014) 9 SCC 716, where the issue was whether the state of Uttar Pradesh could make ‘Urdu’ a second official language. I was in favour of Urdu being added as an official language.

A constitution bench led by Chief Justice R.M. Lodha found this decision of the state to be valid and said that the “constitution does not foreclose the state legislature’s option to adopt any other language in use as official language”. It noted that many states have followed such an approach including Bihar, Haryana, Jharkhand, Madya Pradesh, Uttarakhand and Delhi, which also recognises Hindi, English, Punjabi and Urdu.

The test is that the first or second language should be ‘used’ in that state. Tamil is used in Tamil Nadu and other languages in their respective states. The court said: “It is said that law and languages are both organic in their mode of development. In India, these are evolving through the process of accepting legitimate aspirations of the speakers of different languages. Indian language laws are not rigid but accommodative – the object being to secure linguistic secularism.”

The Union should back off from its archaic three–language formula and allow Tamil Nadu and other states to develop their own languages as official languages to be taught in schools. At present, we do not have a ‘national’ language – nor can the Hindi states impose one. The link language that has been effective is English and Hindi if they are agreed by the states mutually.

This is where an undeserving linguistic dictatorship can wreak havoc. Hindi is supported by demography in the North; the rest of the country speaks through different cultures and articulates in different tongues. Linguistic dictatorship will destroy the federation. Healthy checks and balances are needed so that all Indian cultures are articulated, expressed and nurtured in their own tongues. It is not for the Centre to impose a linguistic federalism on those who view themselves differently but are passionately Indian.

I will not dwell on the present government rewriting history officially and unofficially ignoring checks and balances; and secularism which is a part of the basic structure of the constitution to protect India’s unparalleled diversity.

III. The underlying texts of the constitution

At first sight, it is difficult to fathom India’s sprawling constitution. It has 395 Articles, many Sub-articles, 12 elaborate Schedules –each the size of many constitutions in the world. It has been formally amended 106 times, and through various legislations, under different allied Acts of parliament and under other provisions of the constitution, 46 times without reference to the complex process of amendment in the constitution.

Some people say we should redraft our constitution, which was a creative compromise with many elements of democratic surrender by her people to constitutional authorities. I have described this in a book titled he Constitution of India: Miracle, Surrender, Hope” (2017). I dedicated that book to Fali Nariman, my distinguished friend, who used to say that we will never be able to draft a new constitution now if we want, because people will fight over everything and come to a conclusion only through unwelcome crude political majorities.

But, in his last book, he advised, “you must know your constitution”, and showed how to maneuver its complexities –a notable and commendable effort. His latest, beyond the Courtroom: Reflections on Law, Constitution and Nationhood reminds us of India’s democratic gift to itself.

I need to explain that all constitutions invoke a surrender of rights, liberties, hopes and expectations during constitution–making and after. It is left to those who work out the constitution to ensure that this, or any other surrender, is not inimical to the people the constitution serves. It is in civil society that we will find hope for the future.

To understand the underlying thread of the constitution, I identify the following texts:

- The Democratic and Political texts

- The Justice texts

- The Federal texts

- The Civil Service texts

- The Military texts

Each of them are fundamental in their own right, but interact with each other under a system of checks and balances.

The democratic and political texts are huge and contain many provisions to include a common electoral roll without discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste or sex (Article 325), and elections to the parliament’s lower house and state assemblies on the basis of adult suffrage, which now means a right to vote if above 18 years of age (Article 326).

There are no special seats on the basis of religion, the kind demanded by Muslims and others which led to Pakistan. I sometimes feel that in those heady pre-Independence days, we could have conceded special or general electorates for Muslims to preserve an undivided continent to keep it together and save us from the horrors of Partition. I read the accounts from July 1946 with anger and dismay; though it may well have been that by that time the die was cast.

I canvass better relations with our neighbours, especially Pakistan, which I visited. Our fundamentalist friends cannot understand the importance of this.

The Election Commission is an independent constitutional body to ensure free and fair elections. There is some contemporary concern about appointments to the membership of the commission, which has ousted the chief justices in the selection process and admitted it to political domination. This is a blow to electoral constitutionalism and the system of checks and balances which accords independence and autonomy to the constitutional body. We need a wide-bodied committee to suggest names which are confirmed by parliament to save the neutrality of this important commission.

A Delimitation Commission organises the constituencies; and the judiciary determines electoral disputes. The South, with more birth control and lesser populations, fears delimitation will diminish their strength in the elected legislature. All this will affect the checks and balances of the constitution in these texts. The South should not get lesser seats due to the demography of the North.

But there is cause for worry. Justice Madan Lokur has rightly pointed out that executive responsibility to parliament is decreasing. Richard Crossman elaborated that with the rise of prime ministerial power, there are strong presidential elements in the parliamentary system. One can see this in his posthumously published Crossman Diaries and a lecture in Harvard.

But though insightful, we still have a president who has to act on the aid and advice of the cabinet, with some independent powers. Another check and balance. But Crossman was concerned with the prime minister ascending power over his own cabinet and the latter’s discourse. To do so is a failure of checks and balances enshrined in India’s constitutional texts (Article 78, especially Articles 75(3), 78, 163, 164(2) and 167).

In India, the rise of a powerful Prime Minister’s Office centralises power in a disturbing way. Modi has appropriated considerable power to himself. This should serve as a warning.

There is also concern about the Delimitation Commission re-organising constituencies in a politically biased way and the danger of the Election Commission losing its autonomy due to political pressure. In a significant decision called Abhiram Singh (2017), Justice Lokur led a thin 4:3 majority to hold that appeals to religion in election were not permissible. This trumped the minority view of the then–Justice Chandrachud, Justice Lalit and Justice Goel – all of whom had some saffron connections or tendencies.

I leave this discussion on the political and democratic texts with apprehension because of the danger they portend. The apprehension deepens because debates in parliament are lessening. I demonstrate this in my book Reserved! How Parliament Debated Reservation 1995-2007 (2008) and other essays on other legislations.

Excessive control of parliament discussion weakens faith in this prime body. Quite apart from the paucity of debates on legislations and on President’s Rule proclamations, governments’ majorities dominate committees as we can see on the Waqf Bill.

Discussion on issues is stage–managed by speakers and the dreaded Vice President Jagdeep Dhankhar (a veritable hit man for Modi’s government who does not understand the importance of the neutrality of his role). The result is that when the opposition disrupts proceedings to demand discussion, they are blamed for subversion, overlooking the genuine demand for discussion and debate.

The justice texts: The justice texts are crucial for democracy, federalism and civil liberties. But two clarifications are necessary.

The justice texts are not just addressed to the judiciary but to all organs of government including the executive, parliament, civil services, the federal structure and the military.

There are special texts in the constitution to monitor and give justice to the untouchables (chedule Castes (SCs)) and Schedule Tribes (STs), who also have presence in the legislatures, and at a lower level in local government to SCs, STs along with the other backward classes (OBCs) and women.

Many years ago, I printed a long article arguing for one-third women’s representation in legislatures. That is now law waiting to be implemented.

There are several constitutionally appointed commissions to work towards the upliftment of the marginalised (Articles 338-342A). But there is concern that there is an over–concentration on ‘reservation’ by way of quotas in services and access to education. In many cases I have supported reservations but for principled limits on the inclusion and exclusion of claimants. I also feel that not enough is done regarding direct affirmative action programmes.

But the core of the Justice texts lies in the fundamental rights chapter (Articles 12-36). Here are provisions of equality, liberty, freedom, protection of religions, their faiths, beliefs and practice, enhancing cultural rights and, most important, reposing in the judiciary with the right to move to the high court and directly the Supreme Court when these guaranteed rights are in threat.

Crucial to the independence of the judiciary are appointments to the higher judiciary. In Nehru’s time, the executive consulted the judiciary and this worked reasonably satisfactorily even if Nehru bitterly complained that lawyers (surely including judges) had, in his phrase, “purloined the constitution”. The record of this cooperation is recorded in the second collegium case.

But although his parliament reversed some important judicial decisions, checks and balances were in play over judicial appointments. It was Mrs Gandhi who saw threatening clouds to her power that she wanted a “committed” judiciary. Committed to what? Her regime or the constitution? Principled constitutional governance? She fiddled with these appointments when she lost important judicial decisions, more so after her election to parliament was declared invalid by an Allahabad high court judge.

This led to the Emergency, where otherwise brilliant judges in the Supreme Court gave her unbridled powers over political and other preventive administrative detentions against the decisions of nine high courts.

The judiciary came out of the Emergency badly wounded. The judges responsible for the disaster apologised in different measures –some were defiant. I do not believe that the judiciary would have survived this debacle but for Justice Krishna Iyer inspiring Justices P.N. Bhagwati, Y.V. Chandrachud (those two being party to the Emergency decision), Chinnappa Reddy, D.A. Desai and others to rely on a new approach and jurisprudence.

But as far as judicial appointments were concerned, the end result was that the Supreme Court in three important decisions of 1982, 1993 and 1998 struck back to eventually give itself dominant control over appointment through high court Collegiums and finally, as the decider in the Supreme Court collegium.

But this dominant power has been thwarted by covert and overt government interference. In 2014 the constitution was amended to create an independent National Judicial Appointment Commission (NJAC). This was struck down by the Supreme Court as politically dominated in the Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Assn. case (2016).

Although I participated in the case that led to the NJAC’s downfall, I am not sure if I was right. Maybe the NJAC would have been more transparent, as my personal faith in the collegiums has declined. But I remain unsure. What we need is a wide–based commission whose decisions are ratified by parliament.

The entire controversy over Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud’s tenure was really over his failure to protect the checks and balances of the constitution. Photo: PTI.

I also believe that in Modi’s time, the judiciary has sought to be saffronised with independent judges like S. Muralidhar taken out and regime judges like Victoria Gowri and Shekhar Yadav brought in. How much saffronisation? I cannot say, as this requires more research.

The entire controversy over Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud’s tenure was really over his failure to protect the checks and balances of the constitution, in his decisions as master of the roster to allocate cases, in judicial appointments with perceived religious biases, and his almost psychotic love for publicity.

So how have the justice texts fared? In response, the Supreme Court has spread itself into too many areas. The judiciary is overburdened. But the courts, especially the Supreme Court, still have the respect of the people. If the courts act independently and remain independent, there is more than hope for the future. However, we must remind ourselves again that the justice texts are not just to the judiciary but also to the other organs of government; and, of course, all of us.

The federal texts reflect India’s diversity. India now has 28 full fledged states and nine Union territories administered by the Union with some democratic governance in Delhi and Puducherry. After the dismemberment of the state of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), there is one less state and two more Union territories, J&K and Ladakh.

These constitutional divisions are based on linguistic and cultural differences and strengthen diversity, secularism, democracy and governance itself. However, the working of Indian federalism has led to critical attention through public discourse, the Governors’ Report (1971), the Tamil Nadu Report (1969), the Sarkaria Commission Report (1988), the Constitution Commission Report (2002) and the Punchi Commission Report (2010). Of all these, the Sarkaria Report is the deepest.

One cannot ignore the vast research done by academics, of which my friend Balveer Arora who is on the stage, and Zoya Hasan are examples, amidst so many others including state governments and a vigilant media.

India has been called a quasi-federal state. The term has gathered currency because of the dominance of the Union and its huge powers. This argument of central domination is partly unsatisfactory, because all large federations are centralised in their power distribution but should be more sensitive in their working. Elsewhere I have argued in 1966 that India is quasi–federal because territorial integrity is denied to the states.

Gautam Bhatia, a distinguished jurist, in his latest book Constitution of India (2025) shows that the Supreme Court has contributed to this centralisation. This is only partly true, but the court has also tried to arrest the abuse of political federalism and has recently given greater mining rights to the states and chastised the outrageous behaviour of governors appointed by the BJP to behave responsibly in the discharge of their constitutional functions.

Governors have become political ‘hitmen’ for the government in power at the Centre. More recently, their conduct has become embarrassingly perverse.

The federal texts demand “cooperative” federalism. We can see this in Canada and perhaps Australia, but less so in America after the election of President Trump. Cooperative federalism is partly through institutions like the Inter-State Council (Article 263) or where there is meaningful exchange at formal and informal levels in respect of the distribution of power, the allocation of finances, interaction and mutual respect for each other’s governance. But this requires political will, often lacking in Indian federalism.

The Inter-State Council, which was resurrected after four decades, has fallen into disuse. Political interference is manifest in many ways. It began aggressively during the first reign of Mrs Gandhi when she used the President’s Rule provisions in Article 356 to oust and demolish opposition parties that had succeeded at the polls to establish their governments in many states.

Other political parties have also used these provisions mercilessly. The Janata government dismissed nine opposition governments in 1977 claiming a massive electoral mandate and the Congress returned to do the same in 1980.

These travesties continue. President’s Rule has been imposed 134 times, including 11 during the BJP’s tenure since 2014.

I believe that Article 356, which houses the power to impose President’s Rule, should be abolished, because as a result of these impositions, democratically elected governments simply disappear and consequently the state is run by parliament and the executive at the Centre.

External threats and public order problems can be dealt with by cooperative means. The general Emergency provisions (Article 352) or financial emergency provisions (Article 360) can be invoked with caution, because under this use of Emergency powers, democratically elected state governments survive as they should. This is also a part of the sustained duty of the Union under Article 355, which states that “it shall be the duty of the Union to protect every state against external aggression and internal disturbance and to ensure that the government of every state is carried on in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution”.

Although this has been emphasised because of the need to deal with war and revolts and also justify the imposition of President’s Rule in erring states, it gives the Union ample power to protect the nation; and properly interpreted, imposes a duty not to take over the democratic governance of the state but enhance it without imposing President’s Rule and abolishing legislative democracy in the states.

At the core of the abuse of political federalism are the governors appointed by the Union government. I believe that earlier some governors acted with constitutional honesty even though it was often with disastrous results. When I interviewed governor Dharma Vira for a book, he told me that he may not have been wholly correct in not giving the Mukherjee ministry the 18 extra days it wanted to face the assembly. I also believe that my father, governor Shanti Swaroop Dhavan, should have allowed Jyoti Basu to have formed a minority government in West Bengal.

Some but not all governors acted with honesty. But the BJP’s governors like Jagdeep Dhankhar (West Bengal), R. N. Ravi (Tamil Nadu) and Arif Mohammad Khan (Kerala) are a disgrace to the office. Dhankhar as vice president continues to espouse the BJP’s politics, refusing to maintain the neutrality of his office.

I believe governor selection needs approval by an evenly politically distributed parliamentary committee after extended consultation with the state in question to result in the appointment of non-partisan governors who should not be transferred until they complete their five–year term unless impeached earlier. After their term, they should be ineligible for further gubernatorial office more than twice after going through impartial selection again for a possible second term.

Who should form a ministry after election or otherwise cannot be decided in Raj Bhawans. Even a minority ministry of the largest party or coalition should not be enjoined to face a ‘confidence’ motion. Once sworn in, they should only be toppled by a ‘non-confidence’ motion. This should be true of parliament and state assemblies. An instrument of instructions needs to be devised.

Abuse of political federalism was addressed by the Supreme Court in the Bommai case (1992) and the Rameshwar case (2005) to provide for judicial review of the decisions to impose President’s Rule. When the Uttarakhand President’s Rule was struck down by the high court, the BJP government was indignant and discriminated against the judge’s elevation to the Supreme Court.

We should remember that judicial review is a backstop. It would be better for the Presidents Rule provisions to be abolished.

A distinguishable feature of Indian federalism is its asymmetry. Not all states are alike and cannot be treated as such. This asymmetry is manifest in special provisions in the constitution for the states of Gujarat, Maharashtra, Nagaland, Assam, Manipur, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Sikkim, Mizoram, Arunachal Pradesh, Goa and Karnataka.

For Nagaland and Mizoram, even the parliament cannot interfere with cultural religious practices (Article 371 and 371 A to J). Areas of states with tribal populations are protected (Fifth Schedule) even if Supreme Court decisions in the Andhra and Chhattisgarh cases have been conservative in not providing for a protective shield in this Schedule.

Significantly for Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura and Mizoram, there are constitutions within the constitution in these states (Sixth Schedule), with other significant autonomies (Article 244A).

Given this, it should not surprise us that the state of J&K was governed by two interacting constitutions at the Union and state levels. The provisions for these two constitutions was called ‘temporary’ because the J&K state constitution was yet to be finalised not as the Supreme Court used this term to destroy the J&K state constitution through executive decisions and legislation passed hurriedly through parliamentary majorities.

Succumbing to the government, the Supreme Court upheld these decisions of a BJP majority parliament with no discussion. This merits an explanation.

In 1957, parliament enacted the Constitution (Seventh Amendment) Act, whereby two provisions (Articles 152 and 308) ordained that parts of the Indian constitution relating to the constitutional governance of state governments (some 100 Articles) and administrative services (some 50 Articles) would not apply to J&K because they were covered by the J&K constitution. These important provisions could only be changed by the rigorous procedure of constitutional amendment (Article 368).

But, subverting this, the Supreme Court decided that they could be changed by executive order without confronting this argument at the bar.

The J&K imbroglio rested on provisions in the constitution to alter state boundaries or change their status (Articles 3-4). These are draconian provisions which could be used to deny the territorial integrity or constitutional status of a state. These provisions may have been necessary because many aspects of the Indian federation were incomplete when the constitution was inaugurated in 1950. These provisions provide for consultation of the state legislature which, the Supreme Court in Babu Ram’s case (1960) diluted.

In the case of J&K, since there was President’s Rule in the state, parliament was unable to consult the state legislature and de-facto consulted itself as a substitute. Those provisions should be reconsidered and amended for more and better consultation.

It is time that India realised that except for large States like Uttar Pradesh or the singular case of Vidarbha, the territorial process that forms the basis of Indian federalism is now complete. When the J&K case reached the Supreme Court, the judges colluded to reduce a mighty and respected state with Muslim dominance but cultural diversity into two Union territories with a vague promise that statehood would be restored in some uncertain future. This was not the Supreme Court’s finest hour.

All governments need adequate finances. Much can and has been written about India’s financial federation, which provides for fiscal levies by the Union and states with greater powers of taxation in the Union and their distribution and grants by the Union government. Reports of the Finance Commissions have been pivotal.

The Planning Commission was a supra-constitutional body now replaced by the truncated NITI Aayog. The 15th Finance Commission, which came into play in November 2017 in the aftermath of the then–recently introduced GST, was reposed with a continuing function to examine grants and review tax devolution to honour the conditions under which it was created and with a caveat on performance–based incentives which may eclipse endemic need–based requirements. This commission favoured the Union government.

GST poses a problem as the GST Council has recommendatory problems and an essential dispute–settlement machinery has not been set up.

A distorted political federalism has joined hands with economic federalism. There is rank favouritism towards those political parties in power that have joined or allied with the BJP–dominated National Democratic Alliance in power in the Union government. The other opposition states are under–resourced. In federal matters, existing checks and balances are being undermined and old statutory mechanisms are being dismantled. New mechanisms undermine a healthy financial federalism.

The civil service texts are important for the selection of the civil services. These are the backbone of Indian governance. To obviate political interferences, the selection of civil servants was entrusted to Public Service Commissions for the Union and states to ensure the independent selection of civil servants, including the police (Part XIV, Articles 308-323).

To ensure that civil servants act independently, there are provisions to ensure that they are not dismissed, removed or reduced in rank without due process (Articles 311-312). The idea was that they should be able to stand up to the political executive without fear or favour.

Unfortunately, successive political executives have violated these provisions, with the result that there is mighty litigation by civil servants in tribunals, high courts and up to the Supreme Court. What a colossal mess. The very size of this litigation shows that members of the civil services are disgruntled by constantly arbitrary and discriminatory treatment by executive governments. This does not augur well for the performance and independence of civil servants.

Remedial litigation also shows how civil servants are transferred if not liked by the political party in power – an issue where the courts have protected the powers of the executive.

Now, the Union government seeks to make outside special appointments in a relatively arbitrary and unregulated way. Checks and balances have gone and need to be restored and innovated.

I now turn to the military texts. Army recruitment is by the Union government, which has generally respected the autonomy of the army, which unlike Pakistan has not converted India’s democratic polity to hand over total powers to the military. But there are provisions in the constitution to modify the fundamental rights chapter in relation to the armed forces and when martial law is in force (Articles 33-34).

Why is this important? The army has a huge presence in the seven northeast states and J&K. They have enormous powers. We challenged the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act of 1958 with shoot-to–kill powers in the Supreme Court which demurred, refusing to interfere or even lay down guidelines.

At one stage, Justice M.N. Venkatachaliah, when chairman of the National Human Rights Commission, called a meeting of all the concerned top generals to meet with activists. This afforded a frank exchange, but the army did not yield to greater accountability even in respect of allowing independent observers in court martials.

Military operations also precipitate a ‘deep’ state where people are killed or illegally detained or imprisoned. This is hidden from view but surfaces. We need to know more about this deep state and have more accountability from the army and military without interfering in operations.

Since the topic for the day is federal democracy, I have addressed the issue more elaborately and mirrored my concern about checks and balances in the working of the constitution. The inauguration of more direct democracy at the village and city level is discussed in the next part although germane to India’s three–tier federalism.

IV. Separation of government from state

The state is created by the constitution which is permanent. Governments formed under te constitution come and go. The latter may make policies but must operate within the framework of constitutional limitations.

I was reminded of this by Balveer Arora’s recent and much publicised television speech. Today’s government and state are being unified as if the constitutionally created state is a play thing. I think Rahul Gandhi was prompted by his advisers to declared that the Congress will take its fight to the state itself. This was an ill-advised comment, which received much flak and reflects ignorance.

Our object is to save the state which is being taken over by the government to rewrite India’s history, diminish diverse cultures and claim absolute powers so that attention is diverted from the constitutional framework and its imperatives to the ambitions of the government in power and the iconisation of leaders to dwarf anything that stands in their way being undermined.

India is not Indira nor is Indira is India. Nor Modi is India and India is Modi.

V. Constitutional morality

When Ambedkar reviewed the constitution making of the Constituent Assembly, he expressed two caveats of considerable significance.

The first was that this ‘magnificent’ constitution would fail if good men failed to implement it.

The second connected concern was expressed by referring to George Grote’s view of constitutional morality in ancient Greece. This was generally ignored because the members of that august body believed that there were enough men and women of character amongst them and their successors who would take over constitutional governance even though they were wary that many constitutional provisions had flaws and could be politically subverted.

Even so, they believed that in the constitution’s processes and institutions with its checks and balances would work even after partition and Gandhi’s demise.

It is said that in one memoir written by someone other than Gandhi, it was projected that the latter believed in direct democracy at village levels which though inserted in the unenforceable Directive Principles emphasised the importance of panchayats at the grassroots level.

Perhaps this dream was fulfilled in part by the panchayats amendments in rural area and urban settings (Part IX – Article 243(H) to 243(T)). Added to this dream was the Panchayat Extension to Schedule Areas Act, 1996, which gives a dominant role to gram sabhas consisting of the entire village population to control predatory mining entrepreneurs and others.

My dear friend B.D. Sharma, in his weekly meetings with me, felt that the Act has lost its efficiency because the decisions of the direct democracy sabhas were not mandatory.

What our constitution needs are structural changes to promote democracy at all levels and also address the issue of an ‘operational’ morality to address not just the silences of the constitution but its operation across the board. This does not require a new constitution, but a partial re-examination based on consensus.

A new breakthrough came when the Fundamental Rights case (1973) decided that the basic structure of the constitution could not be altered by constitutional amendments. This could have been a doctrine of limited significance if it applied only to arrest constitutional amendments. But Bommai (1992) also used this doctrine to examine the executive action of imposing President’s Rule on various states and declaring that ‘secularism’ was part of the basic structure which was violated by these impositions.

Needless to say, democracy, judicial review and the independence of the judiciary are also part of the basic structure as well as aspects of fundamental rights as explained by Chief Justice Chandrachud (senior) in the Minerva Mills case (1978), which linked the equality, freedom and liberty provisions as part of a celebrated ‘golden triangle’.

It was not entirely clear whether the basic structure provisions could invalidate statutes and were only a means of interpretation. The better view is that it has more general application.

Perhaps born out of the basic structure doctrine, but standing tall as a self standing imperative for constitutional understanding and interpretation, it has bred more radical versions, described and articulated as ‘transformational’ morality on ‘constitutional novelty’. These are innovative doctrines not just, as Madan Lokur pointed out, to deal with the silences of the constitution, but of greater significance. It grew from Supreme Court decisions of Justices Dipak Misra and Chandrachud with some support from others.

My basic concern about constitutional morality is its relativism. Whose constitutional morality? The court’s? Or some judges’? Do Modi and the Sangh parivar have a different “Hindu” view of constitutional morality to rewrite history or legislate for change or even press for a new Hindu constitution which is being explored? Was a Uniform Civil code an issue of constitutional morality?

Judges have differed on its content and application. In the Sabarimala case (2019), Justice Chandrachud emphasised the egalitarian and libertarian provisions of the constitutional text as constitutional morality. Justice Indu Malhotra emphasised plural secularism. Both views led to different results.

At the end of my now dated book on President’s Rule in the States (1979), I talked all too briefly of institutional morality. By this I meant that every institutional authority, every constitutional or statutory functionary and every process of governance has a best practice.

Without elaborating, I wanted all those in power to yearn towards the best practice constituting institutional morality; and to advance the dharma of constitutional governance. Subjectively, this draws sustenance from the Mahabharata to ask each one to find their dharma and move towards its fulfillment of best practice. Many fall short of this requirement – as they do in our time. But I believe institutional morality to be a more workable solution.

VI. Conclusion

I will not attempt a summary of what I have said on elected dictatorship, the checks and balances of the constitution, its manifestation in the five texts of the constitution (the political or democratic texts, the justice texts, the federal texts, the civil service text and the military texts), the need to separate government from the state and exploring the morality of the constitution.

My concern reflects on our challenges in 2025 as they have now emerged after 75 years of governance with all their ups and downs. These challenges have to be addressed by civil and political society and all of us whose future destinies are invested in this great nation for now and generations to come.

To borrow from an American poet: India is large and contains multitudes.

This article is based on the author’s lecture delivered at the India International Centre on January 25, 2025.

Rajeev Dhavan is a senior advocate.

Courtesy: The Wire