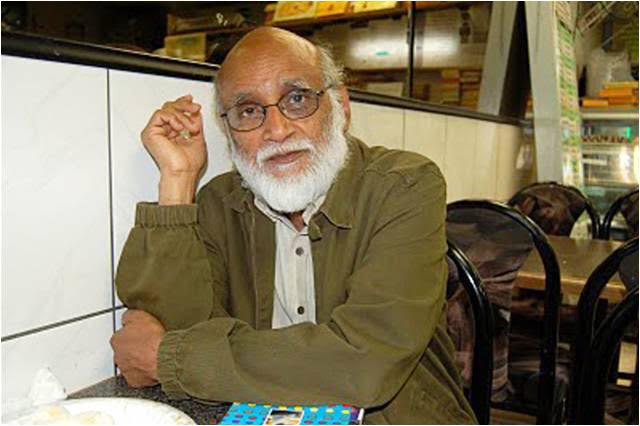

Chaudhry Mohammad Naim (1936-2025)

Born in Barabanki, and having earned various degrees from, and having served in several American Universities (California, Chicago, Minnesota, etc.), C.M. Naim had a rich academic life.

For decades, I have been reading C M Naim, his essays, books, columns, translations…. And just a few months back (on January 4, 2025, to be precise), he wrote to me, on email, to encourage me to keep writing on Aligarh Muslim University (AMU).

His email, verbatim, can be read here:

“Dear Prof. Sajjad,

I’m a retired academic, living now in Chicago.

I have been reading your ‘against the grain’ essays and notes in Urdu and was delighted to read your thoughts on Hameed Dalwai.

Muslim elite of all hues have been suffering this victimhood syndrome. They in fact revel in it. The poor, the helpless, those who had no choice in 1947 and their children and grandchildren have suffered. With no end in sight. While the so-called maulanas have flourished, safe in their sanctuaries. English-speaking Muslim public intellectuals have done the same, secure of acceptance and praise from the liberal non-muslim writers, who do a brave job countering their co-religionists opponents but never challenge Salman Khurshid, Talmiz Ahmad, and so many others who never challenged Nadvis and Tablighis.

Keep up the good work. AMU is a hard place to carry such opinions but someone has to be there to help the young think clearly about their lives in India. Our only bosses/clients in academe are our students. We must be honest with them.

Warm regards,

Naim”

Last year, few of us had thought of suggesting that the AMU requests his consent to accept the AMU-established, Sir Syed Excellence Award. He, however refused, rather bluntly, as he did not have very good memories of AMU! He had quit AMU having taught Linguistics briefly.

My 2014 book on Muzaffarpur begins with a quote from his 1999 book, Ambiguities of Heritage: Fictions and Polemics.

In 2014, there was a controversy around access to the central Library of AMU for the undergraduate girls of the Women’s College. I had written a column, disliked by many, particularly those pretending to be feminists or gender activists. They are those who never speak out against the tormentors of the likes of Shaha Bano (1916-1992) and Shayera Bano.

Naim’s letter to the editor in The Indian Express (13 November 2014) was a source of affirmation for what I had written, concurrently. My Rediff column, “AMU gender row: Reinforcing Muslim stereotypes”, was published (Nov 14, 2014). We were on the same page, on the issue.

Naim wrote:

“I am not an admirer of the Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) administration and am strongly opposed to having retired non-academic institutions simply on the basis of religion. But The Indian Express report (‘Row in AMU Over No Library Access to women undergrads’, IE, November 12) on the alleged discrimination at AMU was merely shrill and did not mention much that was highly relevant. First, the matter concerns only undergraduate students, not all women students. Second, undergraduate students are not denied use of the main library during daylight hours. Third, undergraduate girls live in the hostels of the Women’s College, a long distance away from the main library. For their safety after dark—a responsibility of AMU and a commitment to their parents- they will have to be bussed both ways. Fourth, the College has its own library and reading rooms. Have they been found to be inadequate for the undergraduate students? If so, what are the inadequacies for the undergraduate students and can they be easily removed? As far as I understand, the college library is sufficient for the needs of undergraduate students and also has the ability to obtain books for them from the main library if needed. Fifth, again, at issue are the needs of undergraduate girls living in hostels, many of whom would be considered, “minors” in other circumstances. Should we not seek the opinion of their parents, who have entrusted their daughters to AMU? The tweets and the report both displayed only politically correct reactions, not careful thought”.

- M. Naim, Professor Emeritus, University of Chicago

Soon after, he made an intervention into the EPW (Vol. 50, Issue No. 30, 25 Jul, 2015), through a letter to editor. Caption was “Muslim Communalism”. He wrote:

“While I fully agree with the editorial (“Resisting ‘Sustainable’ Communalism,” EPW, June 27, 2015) and appreciate its urgency and concern, I must point out that there is another similarly corrosive “sustainable” communalism, and that is of a large portion of the Muslim community. It is most obviously expressed in what is easily termed as “sectarian” bias and antagonism. This sectarianism has become more and more blatant in recent years. Then there is also that reflexive communalism that is directed against all Muslims who do not contribute to the sectarianism of these people nor to their exclusivism that is directed against all those Muslims whom they derisively call “secular.” It has been quietly accepted by many liberals in the media. Ordinary Muslim citizens of India need to be protected as much from the communalism of their co-religionists as from what is labelled majoritarian communalism.

C M Naim Chicago”

My friend, Syed Ekram Rizwi had reminded me of his 2010 essay, THE MUSLIM LEAGUE IN BARABANKI: A Suite of Five Sentimental Scenes. This was a wonderful read, full of insights, particularly with regard to the way things unfolded during august 1947 to January 1948 and after.

The same year Naim published a wonderful essay, “Syed Ahmad and His Two Books Called ‘Asar-al-Sanadid’”. This was in the formidable academic journal from the Cambridge University Press, Modern Asian Studies (2011). The chief questions that the paper explored, were, “How do the two books differ from some of the earlier books of relatively similar nature in Persian and Urdu? How radically different are the two books from each other, and why? How and why were they written, and what particular audiences could the author have had in mind in each instance? How were the two books actually received by the public? And, finally, what changes do the two books reflect in the author’s thinking?”

Naim’s EPW (April 27, 2013) essay, “The Maulana Who Loved Krishna”, on F H Hasrat Mohani, was a wonderful read, also carried by the Outlook weekly, in its slightly abridged version. This article reproduces, with English translations, the devotional poems written to the god Krishna by a maulana who was an active participant in the cultural, political and theological life of late colonial north India. Through this, the article gives a glimpse of an Islamicate literary and spiritual world which revelled in syncretism with its surrounding Hindu worlds; and which is under threat of obliteration, even as a memory, in the singular world of globalised Islam of the 21st century.

Another essay by him, “The ‘Shahi Imams’ of India”, Outlook, Nov 27, 2014, offered a historically informed critique of the authority handed over to these anti-historical, superficial characters (clergy), by the unsuspecting, gullible masses of Muslims, not without the support of the state actors of the Indian Republic.

C M Naim’s essays on the portal, New Age Islam, are:

(1) Seminar On Iran Held At Raza Library: Should Such Things Happen At A National Institution In India? (30 June 2012)

(2) “Muslim Press in India and the Bangladesh Crisis” (2 Sept 2013): In this he examined how Muslim public opinion responded to the Bangladesh struggle in 1971, how those responses compare with the reactions in Pakistan, and whether that crisis left any lasting effect on the thinking of Indian Muslims.

Going by what Shyam Benegal (1934-20124) argued in his essay, “Secualrism and Indian Cinema” that the film like “Garm Hawa” could have been made only after the Bangladesh (1971) issue which convinced the hitherto un-convinced Muslims of India that religion could not serve as a binding force of nationalism.

(3) “Another Lesson in History” (19 Sept 2013);

(4) “English/Urdu Bipolarity Syndrome in Pakistan” (19 Dec 2014)

(5) “Listen To Sonu Nigam, Please” (20 April 2017)

His essays are available on his website: https://cmnaim.com/; This includes his essays published in the Annual of Urdu Studies (Wisconsin, USA), which he edited too, and his EPW (June 17, 1995) essay, “Popular Jokes and Political History: The Case of Akbar, Birbal and Mulla Do-Piyaza“.

In 2004, he brought out a collection of his essays, Urdu Texts and Contexts. The book primarily focuses on Urdu poetry, offering fresh perspectives on diverse Urdu texts and their significance in India’s cultural history. It explores literary, social, and performative contexts associated with Urdu in South Asia and beyond, addressing themes such as Urdu poetry (including ghazal and marsiya), the sociology of literature, and the social history of Muslims in North India. The essays cover topics like the works of poets such as Ghalib and Mir Taqi Mir, the musha’irah tradition, and the role of Urdu in education and popular fiction. Naim’s accessible yet scholarly approach makes the book valuable for those interested in Urdu literature and South Asian cultural studies.

Naim’s latest (2023) book, Urdu Crime Fiction, 1890–1950: An Informal History, is a meticulously researched exploration of the origins and evolution of Urdu crime fiction, or jāsūsī adab, during its formative years in colonial India. The genre, initially inspired by 19th-century European and North American crime fiction, was adapted into Urdu through translations, transcreations, and original works. The book highlights key figures like Tirath Ram Ferozepuri (1857-1924), who translated over 114 titles (spanning 60,000 pages), and Zafar Omar, whose 1916 transcreation of Maurice Leblanc’s Arsène Lupin as Bahram in Nili Chhatri (The Blue Parasol) became a cultural phenomenon. Other notable contributors include Nadeem Sahba’i, known for imaginative Urdu pulp fiction.

Naim details how Urdu thrillers, with evocative titles like Khūnī Chhatrī (The Murderous Umbrella) and Mistrīz af Dihlī (The Mysteries of Delhi), captivated readers with their “wonder-inducing” and “sleep-depriving” narratives, selling thousands of copies.

These works reflected urban India’s modernity, incorporating elements like mannequins, cameras, and truth serums, while depicting secular spaces—railway stations, public parks, and cinemas—where diverse identities mingled. The book also notes the influence of Western authors like G.W.M. Reynolds and the absence of female Urdu crime fiction writers during this period.

Naim’s primary focus is on the genre’s development before 1950, slightly predating Ibn-e-Safi’s most prolific period. Naim acknowledges Ibn-e-Safi (pen name of Asrar Ahmad, 1928–1980) as a transformative figure who elevated Urdu detective fiction to new heights in the post-independence era.

While earlier writers like Tirath Ram Ferozepuri focused on translations or transcreations of Western works, Ibn-e-Safi’s original stories, blending suspense, humour, and social commentary, popularized the genre further, making it a cultural staple in South Asia.

We will miss the “against the grain” essays of C M Naim which were incredibly historically informed.

Rest in Peace Naim sahib!

Related: