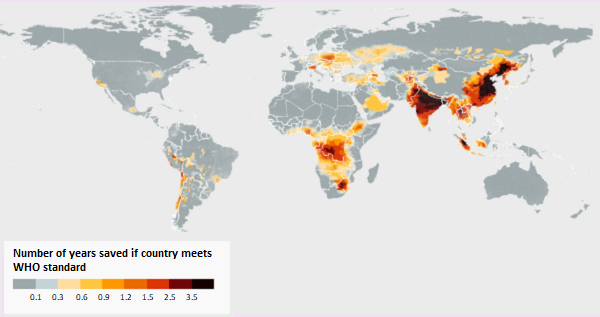

If India reduced its air pollution to comply with the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) air quality standards, its people could live about four years longer on average, the Air Quality-Life Index (AQLI) released today by the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago, shows.

Among India’s most populous cities, the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi would make the most impressive gains in average life expectancy (9 years), followed by Agra (8.1 years) and Bareilly (7.8 years).

The index estimates the number of years a country could add to its people’s lives by meeting national or WHO standards for PM2.5–particulate matter less than 2.5 microns in size, or 30 times finer than a human hair, which, when inhaled, can enter deep into the lungs and sometimes the bloodstream to cause serious harm.

By providing the actual impact on lifespans, AQLI goes a step beyond India’s National Air Quality Index (AQI), which measures the presence of eight pollutants in the air and ranks their levels into six categories of severity.

AQLI shows that by reducing PM2.5 pollution to below the Indian standard–as set by the Central Pollution Control Board, and less stringent than the WHO standard–Indians could live 1.35 years longer on average.

PM2.5

The WHO standard for permissible levels of PM2.5 in the air (annual) is 10 micrograms per cubic metre (μg/m3), but India’s National Ambient Air Quality standard for PM2.5 is three times higher at 40 μg/m3. “The WHO assigns such a low standard precisely because small particulate pollution have been shown to have negative impacts on health even at very low levels,” Michael Greenstone, director of the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago, told IndiaSpend in an email.

The NCT of Delhi, with an estimated 15.5 million people, recorded an annual mean of 98 μg/m3, more than twice the limit considered safe under the National Ambient Air Quality standard and almost 10 times the WHO standard. Delhi stands the most to gain from controlling PM2.5 pollution, with citizens adding nearly six years (5.9) to their lives if national standards are met, and nine years if WHO norms are met.

The index

The AQLI is based on data from studies published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a peer-reviewed scientific journal, which found that a 10 μg/m3 increase in airborne particulate matter of 10 microns in size (PM10) reduces life expectancy by 0.64 years. This PM10 estimate was then applied to global PM2.5 concentrations.

Estimates of ambient PM2.5 concentrations around the world during the year 2015 were taken from the Atmospheric Composition Analysis Group at the Dalhousie University, Canada, which had used a combination of satellite, physical monitoring and simulation-based sources to collect this data.

These measurements exclude dust and sea-salt, considered natural sources of PM2.5, so that the concentrations shown in the map depict pollution resulting principally from human activity.

The AQLI uses concentrations of PM2.5 to estimate how many years a country would add to the life expectancy of its people by adhering to the WHO’s air quality standard of 10 μg/m3.

Source: University of Chicago

Source: Air Quality-Life Index

Note: *Major metropolitan areas that include parts of or all of these districts are included in parentheses.

** Ambient population estimates are from LandScan Global Population Database 2011; administrative boundaries are from GADM database.

The way forward

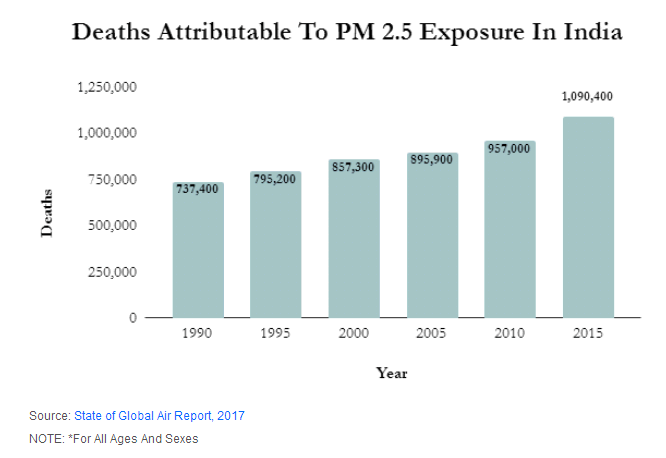

In 2015, 92% of the world’s population lived in areas that exceeded the annual PM2.5 safe limit of 10 µg/m3 prescribed by the WHO, according to the first State of Global Air report prepared in 2017 by the US-based Global Burden of Disease Project and Health Effects Institute. Nearly all (86%) of the most extreme concentrations (above 75 µg/m3) were recorded in China, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

The same year, exposure to PM2.5 was the fifth-highest risk factor for death, responsible for 4.2 million deaths from heart disease and stroke, lung cancer, chronic lung disease and respiratory infections, according to data from the Global Burden of Disease project.

More than 50% of these deaths occurred in China and India, and India is now close to China in terms of deaths attributable to PM2.5. At 1.1 million, China recorded the most mortality attributable to PM2.5, as IndiaSpend reported on July 29, 2017.

Despite evidence to the contrary, the Indian government has denied links between air pollution and premature deaths.

“There are no conclusive data available in the country to establish direct correlationship of death exclusively with air pollution,” the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change told the Rajya Sabha, the upper house of Parliament, on February 6, 2017. “Air Pollution could be one of the triggering factors for respiratory associated ailments and diseases,” it said, enumerating among other factors people’s food habits, occupational habits, socio-economic status, medical history, immunity and heredity.

The scientists behind AQLI, however, believe there is new evidence that proves a direct link. “It is telling that the reductions in life expectancy are entirely due to cardiorespiratory causes of death as this strengthens the case that air pollution is the cause,” Greenstone told IndiaSpend, explaining the results of research his team undertook in parts of China that led them to build the index. “In contrast to most previous work, the study’s context (China) is particularly well suited for extrapolation to India because of the similarities in the countries’ pollution levels and economic conditions.”

Greenstone said there are “tremendous opportunities available” for India to reduce concentrations of PM2.5 and other pollutants, including market-based approaches to regulation such as cap-and-trade programmes that could “greatly reduce the costs of regulation to industry and, at the same time, reduce air pollution”.

India’s Bureau of Energy Efficiency already runs one such market-based programme called Perform, Achieve and Trade (PAT) that enables businesses to trade energy efficiency certificates. Those that exceed their targeted energy savings sell certificates to those who fail to achieve their targets, as FactChecker reported on May 3, 2017.

(Patil is an analyst with IndiaSpend.)

Courtesy: India Spend