Varanasi and Bhadohi (Uttar Pradesh): “I don’t fake things. Sometimes, if I don’t want to speak the truth, I can tell you the extended truth. But I don’t lie.”

As the last phase of Lok Sabha elections unfolds tomorrow, the Bharatiya Janata Party says there is no contest to Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Varanasi. But in the bylanes leading to the holy ghats, there is growing dissent.

At a primary school in Varanasi, Vaibhav Kapoor, Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) leader and head of the party’s social media campaign, made this remark as he explained how the campaign to re-elect Prime Minister Narendra Modi–from a constituency that he won by 581,023 votes in 2014–was going. It was in the bag, Kapoor claimed, as India prepared to vote in the last phase of general elections on May 19, 2019.

As Kapoor, a bunch of party managers and national spokesperson Nalin Kohli told school children about the Swachh Bharat or clean-India campaign, the “truth” they said was that there was no contest here in Modi’s constituency, where he won 56% of the vote in 2014, where people could not–in the telling of party managers–conceive of an alternative. They spoke of the “next step”, what would be after Modi won, new partnerships and trust in the next generation.

Vaibhav Kapoor (left), Bharatiya Janata Party leader and head of the party’s social media campaign, speaks to your reporter at a primary school in Varanasi. “I don’t fake things,” Kapoor says. “Sometimes, if I don’t want to speak the truth, I can tell you the extended truth. But I don’t lie.”

The “extended truth” that Kapoor referred to–hidden from party propaganda–appeared to unfold away from the school premises and its Swachh Bharat pin-up charts.

Among the ranks of the boatmen at the Dasashvamedha ghat–the oldest set of steps going down to the river, where Brahma the creator is said to have sacrificed 10 horses–and local shopkeepers, a consensus appeared evident: If things are so certain for Modi, why is his campaign so shrill? Modi has made personal attacks, for instance, on opposition leader and Congress president Rahul Gandhi, calling his father, assassinated in 1991, “Corrupt No.1”.

This is the story of the quiet voices from the margins of Varanasi, one of 80 constituencies in UP, India’s most important state electorally. Among them were the boatman and his friend–both requested anonymity–who complained how no business was possible each time Modi campaigned because the ghats were closed. Both were Nishads, a group of other backward class (OBC) Hindu communities in UP and Bihar, who traditionally depend on riverine occupations. In 2014, they voted for achhe din, or good days, the promise Modi made. They intended to vote this time for the Congress, which won two seats in the state in 2014 and is contesting 80 in 2019.

| General Elections In Varanasi, 1991-2014 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Candidate | Party |

| 1991 | Shrish Chandra Dikshit | Bharatiya Janata Party |

| 1996 | Shankar Prasad Jaiswal | Bharatiya Janata Party |

| 1998 | Shankar Prasad Jaiswal | Bharatiya Janata Party |

| 1999 | Shankar Prasad Jaiswal | Bharatiya Janata Party |

| 2004 | Rajesh Kumar Mishra | Indian National Congress |

| 2009 | Murli Manohar Joshi | Bharatiya Janata Party |

| 2014 | Narendra Modi | Bharatiya Janata Party |

Source: Election Commission of India

The BJP is also being questioned in its upper-caste Hindu bastions.

Vocal, visible: Modi’s base

Modi’s upper-caste base is vocal and visible.

To the south-west of the ghats, in the largely upper-caste neighbourhood of Chandrika Nagar, first-time BJP legislator Saurabh Srivastava worked up a sweat as he campaigned door to door for the prime minister. Srivastava, 42, won the Varanasi Cantonment seat in the state elections of 2017, and he felt it was his duty to assure Modi a margin greater than the 371,885-vote lead in 2014 over Arvind Kejriwal, chief minister of Delhi.

“Pehle matdaan, phir khan-paan,” First vote, then food.

That was Srivastava’s plea to everyone he met. Most people said exactly what Srivastava expected to hear: “We are all pucca (firm) Modi voters.” One of them had a complaint, or, as he put it: “I’ve made 100 complaints.” As Srivastava jumped over a stinky, dark green stream of sewage spilling across the front porch of the man’s house, he confirmed he was still “an out and out” BJP supporter.

Bharatiya Janata Party legislator from Varanasi Cantonment Saurabh Srivastava campaigns door to door for the Prime Minister in the largely upper-caste neighbourhood of Chandrika Nagar. Most people said exactly what Srivastava expected to hear: “We are all pucca (firm) Modi voters.”

Varanasi city is home to 1.2 million people. It is about 3,000 years old and Hinduism’s holiest city. “Benares (as it was once called) is older than history, older than tradition, older even than legend and looks twice as old as all of them put together,” wrote Mark Twain.

The decrepit city–in UP’s most backward region, the east–has experienced an explosion of attention since Modi made it his constituency in 2014.

The BJP’s hopes are concentrated on winning Varanasi–and the sewage lines cannot keep up.

Sewage flows along the ghats of Varanasi. The city has only half the sewage lines it needs, government data show.

When IndiaSpend asked Srivastava to explain what the Modi government had done to build drains in the city, he began by speaking of his mother’s efforts.

In 2012, when Srivastava’s mother was a legislator from the region, he said, she proposed four new lines to replace the old, narrow and clogged sewers. The first instalment of money for new drains came, but the BJP was not in power either at the Centre or the state. So, work began on only two lines. By 2017, when the BJP did capture UP and also ruled Delhi, only 1.5 of four sewer lines had been built.

But what, Srivastava was asked, of progress since then?

There hasn’t been much more work since then, said Srivastava, because the previous government “ate up” the remaining funds and a new plan for fresh funding money is “still being drawn up”. Varanasi has only half the sewage lines it needs–805 km of 1,596 km required–according to state government officials.

A massive clean-up is evident along the front of the ghats. New roads and flyovers have been built. But behind the malls and hotels, in the back alleys, Varanasi’s extended truth is evident and enduring.

The distrust of minorities

In the gullies behind the Tulsi ghat, there are no drains and no garbage disposal. A few streets away from Chandrika Nagar is the Muslim neighbourhood of Lallapura, where sari weaver Abul Hassan, 58, spoke of a financial crisis affecting Varanasi’s handloom-sarees sector.

Come look at “vikaas” (progress), at the cleanliness in our streets, said Hassan, angrily. This area is right next to the BJP party office, he pointed out. On their side of the road, the street lights were bright and garbage was collected, more or less efficiently. Down the same road, as Lallapura begins, the drains and garbage collection were all but absent.

The Muslim neighbourhood of Lallapura in Varanasi has open drains and garbage strewn across the streets. Further down the same road is the Bharatiya Janata Party’s Kashi region office, where the streets are clean and garbage is collected, more or less efficiently.

“Humney acchey din waley ko na kabhi vote diya tha na kabhi denge,” said Hassan. I have never voted for the harbinger of good days, and I never will.

As Srivastava continued his campaign, some of his supporters spoke of “unsavoury elements”–a reference to Muslims, who make up a third of the city–from neighbourhoods like Lallapura. It was hot. Srivastava was taking a break, chatting with a group of BJP supporters in Chandrika Nagar’s Vinay Kunj apartments.

“Roz yeh thele waley aatey hain jo Kashi ko Kerala bana rahey hain, ek din yaha kattey challenge,” said a man dressed in track pants and tee shirt. Every evening, the men with the carts come here, converting Kashi into Kerala (a state that in the Hindu majoritarian view coddles minorities). One day, country-made pistols will be used here.

The man said he was a long-standing BJP voter and a member of its “intellectual arm”, the RSS or the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh. Srivastava explained what the man meant: that he would like the BJP to “look into this” when it was voted back in the city of holy Kashi Vishwanath temple.

“He is expecting the party to prevent anti-social elements from ruining the area and making it unsafe,” said Srivastava. “Which we will do by telling the police to look into the matter.”

“Dekhiye, kuch logon ko chod ke, baaki Muslim ke chaar biwi, 40 bachchey hotey hain,” said Srivastava. “Look, apart from a few, most Muslims have four wives and 40 children.”

At the ghats, this double-speak of development laced with divisiveness criss-crosses every shop. Himanshu Khanchandani, 31, is a third-generation shopkeeper who represents the new Varanasi. At Jeewan Stores, he sold nighties for women, from the sexy lacy nightgowns to more flouncy, floral ones.

Himanshu Khanchandani’s Jeewan Stores sells nighties for women along the ghats in Varanasi. A Modi fan, he has no time for claims that demonetisation and the goods and services tax hit small businesses like his. Outside the frame, other shopkeepers say “Modinomics” hit them hard.

Khanchandani is a Modi fan. He had no time for arguments against the PM or claims that the demonetisation of the economy in November 2016 and the tax reforms or GST (Goods and Services Tax) six months later hit small businesses like his. A few shops away, it was a different story. A trader who did not want to be named said his business took a 50% hit because of “Modinomics”.

Modinomics pushed UP, which is India’s second-poorest state by per capita income–with an annual average per capita income of less than Rs 45,000, or half the national average–into deeper distress. In eastern UP, the average annual income is Rs 16,522, 15% lower than the already abysmal state average.

Poverty, faith and caste

As the sun set on the ghats alongside the Ganga, it was time for the evening aarti or prayers, a display of faith and exuberance. Five-foot-high speakers played bhajans at high volume, as devotees gathered to watch young men leading the prayers, whirling acrobatically with large multi-tier lamps.

Devotees gather to watch the evening aarti or prayers, on the ghats alongside the Ganga.

Away from the noise, in a quiet corner along the Tulsi ghat, stood a quiet dissenter. Mangal Yadav, 49, chanted the Hanuman chalisa or prayer to Lord Hanuman, in front of a tiny statue built into an alcove along the ghats, in the dark. He lit a clay diya or lamp.

“Dharam ko vyapar bana diya,” he said. He blamed right-wing organisations for converting faith into a business.

Yadav said he was “a devout Hindu”, who argued that the sanctity of his prayers lay in going against the current grain of the city and its loudly proclaimed faith. The aesthetics of the evening prayers, according to him, were mixed up with the prime minister’s politics.

But Yadav’s dissent was not a straight link between sanctimony and commerce. Caste was the ever-present all-pervasive factor in those who opposed and praised Modi.

This is important because scheduled castes–traditionally the most discriminated against–form 21.1% of UP’s population, higher than the national average of 16.2%.

The quiet Hanuman bhakt was a Yadav, a group that has traditionally voted for the opposition Samajwadi Party (SP), a party that popularly referred to as the party of, by and for the Yadavs.

In a quiet corner along the Tulsi ghat, Mangal Yadav chanted the Hanuman chalisa or prayer to Lord Hanuman. “Dharam ko vyapar bana diya,” he says, blaming right-wing organisations for converting faith into a business.

With OBCs, Yadavs are part of a significant social grouping in UP. Taken together, a third of the people of UP are below the poverty line and they are overwhelmingly scheduled caste or OBCs.

As Modi campaigned in the rural districts adjoining Varanasi, caste was front and centre. In a large open maidan in Lalanagar in the district of Bhadohi, he told an audience of about 200,000 that Bhadohi was renamed after the sufi Dalit saint Sant Ravidas, by former chief minister Mayawati, leader of the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), which says it represents the interests of scheduled castes or Dalits.

When Mayawati was voted out in 2012 and replaced by the SP, they changed the district’s name back to Bhadohi. Now, the two erstwhile rivals were in alliance against the BJP.

Using pejoratives for both, Modi asked his Bhadohi audience: “Bua ke baad babua ke aaney se unhone apney ahankar se naam hata diya, kya yeh Sant Ravidas ka apmaan nahi hai? When the aunt (Mayawati) was replaced by the Yadav nephew (Akhilesh Yadav of the SP) then he also changed the name to satisfy his ego. Isn’t that an insult to Sant Ravidas and by implication to Dalits?”

Micro-managing candidates, voters

As Modi spoke, a thin, emaciated man from a dalit caste–75-year-old daily wage labourer Mahi Lal–did not listen to much of the speech. As he saw this reporter approach, he folded his hand, pleading: “I am getting my rations and that’s all.”

Daily wage labourer Mahi Lal (75), a Dalit, did not listen to much of the Prime Minister’s speech at a rally in Lalanagar in Bhadohi district. As he saw this reporter approach, he folded his hand, pleading: “I am getting my rations and that’s all.”

A BJP minder in the crowd quickly arrived on the scene. Harikesh Singh, 24, edged Lal out of the conversation. “I am not in the BJP or a bhakt (fan),” he said; “but I am with the sachhe insaan--the honest man–mannaniya Modi ji, respected Modiji.”

Harikesh Singh (right), a Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) minder in the crowd at Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s rally in Bhadohi. “I am not in the BJP or a bhakt (fan),” he says; “but I am with the sachhe insaan--the honest man–mannaniya Modi ji, respected Modiji.”

Unlike Varanasi, caste politics in Bhadohi is in plain sight. The BJP candidate, Ramesh Chand Bind, an OBC, sat in a motel he owned along the highway in a pink room, with the cupboard door displaying shirts and vests open.

Ramesh Chand Bind (right), the Bharatiya Janata Party candidate from Bhadohi, is surrounded by party workers–including legislator Dinanath Bhaskar (left). Following a politically embarrassing speech, he is watched and micro-managed.

He was surrounded by BJP party workers, who listened carefully to him, especially because Bind made a politically embarrassing speech just a few days ago.

He switched to the BJP only in March 2019 after 18 years in the BSP, Mayawati’s party. As he had done all those years in the BSP, Bind boasted in an election speech how he would put upper-caste people–the BJP’s main voters–in their place.

“Aaj agar ek brahmin ek Bind ko agar peetta hai…toh hum brahminon ko pitwatey hain. [Watch video between 0.27 – 1.08] If today a Brahmin has beaten anyone from Bind, we will beat the Brahmins.”

The speech had embarrassed the BJP’s many upper-caste leaders and voters, and in villages near election rallies held by Modi and Bind people said they would vote for Modi, but, as one said, “we do not want to see the face of the local candidate”.

Like the fearful dalit man at Modi’s rally, Bind was watched and micro-managed.

“That video clip of my speech was edited,” said Bind. “It was doctored.” Then, he added: “Jis samaj ke prati yeh aarop lagaye hain yeh samaj hamesha poojaniya raha hai aur yeh poojaniya rahega. The section of society I am accused of having insulted is actually the section that we all worship.”

Unemployment and stray cows

There is a thumb rule for castes and their political preferences, based on patterns that elections in the past have thrown up: scheduled castes and Dalits vote for Mayawati’s BSP, Yadavs and Muslims for the SP and upper castes and non-Yadav OBC groups for the BJP.

However, when economic distress is as great as it is in eastern UP, and Modi is seen by many voters as not having delivered on his promises, the outliers in each group may provide a picture of the PM’s popularity.

At Modi’s rally, a young upper-caste man, a Brahmin, who did not want to be named, called himself a BJP party worker but in fact turned out to be a dissenter. Over plates of hot chappatis and bhindi subzi (ladyfinger), he said most Dalits who came to Modi’s rally in Bhadohi were there just to see the helicopter.

“Woh madam jahaz dekhney aaye they–phar phar phar phar bolat hai. The phar-phar-phar-phar sound of the helicopter is what they came to see madam,” he said, grinning widely.

The condescension aside, Dalit or scheduled-caste groups appear as divided as others on supporting or shunning Modi. In a village called Natwa near Modi’s rally site, Dalit homes were made of mud, so low that residents had to crawl in.

Dalits in Natwa village in Uttar Pradesh’s Bhadohi district are divided over whether or not to vote for Bharatiya Janata Party and, in effect, Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Even so, 50-year-old Dalit Phool Kumari, said she would vote for Modi because she now had a light bulb. Gayatri Saroj from a low caste called Pasi agreed. But 35-year old daily wage worker, Ganga Ram, a Dalit, shook his head. “Kuch nahi kiye hain Modi. Modi has done nothing,” he said. For the last two years, work available under the national rural jobs programme, which the previous government started, had come to a halt, he said, and there was no alternative launched.

Unemployment is particularly evident in eastern UP. The third generation of a family of BJP voters, the Brahmin party worker we referred to earlier spoke how “no one has a job” and “there is nothing to do except migrate to other states to look for work”.

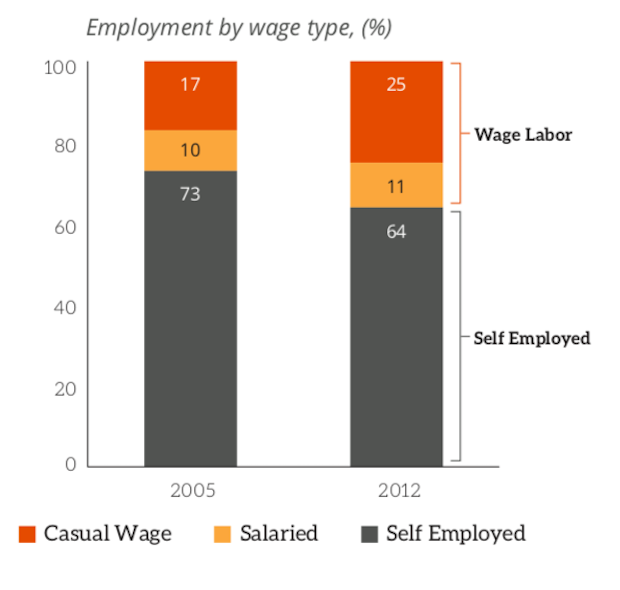

In fact, not only is the unemployment rate in UP high, in the last decade, many more people have become casual labourers, earning uncertain incomes.

Rise Of Casual-Wage Jobs And Self Employment in UP

Source: World Bank, May 2016

Unemployment has worsened in Bhadohi, once a bustling carpet-weaving area. The Brahmin BJP man said that despite being a party worker, “mujhe khud kaam ki talaash hai. Mai khud pareyshaan hoon lekin kisko bataney jaaoon. I am myself in search of work, but who can I tell?”.

Could he not go to the MP? He laughed: “Kya madam aap bhi! Really madam, how could you even suggest that?”

In Natwa, dominated by upper caste Shuklas, about a kilometre from Modi’s rally, farmers–all Shuklas–were divided for and against Modi and out-shouted each other at a grocer’s shop when this reporter visited.

Rajesh Shukla, 35, was passing by when he stopped his cycle. “Modi hasn’t done anything about the unemployment in this region,” he said. Yet, he said, he would continue his loyalty to Modi because Natwa now had electricity for up to 18 hours every day, compared to the five or six hours under the previous government.

In Natwa village in Uttar Pradesh’s Bhadohi district, dominated by upper-caste Shuklas, farmers–all Shuklas–were divided for and against Prime Minister Narendra Modi and out-shouted each other at a grocer’s shop.

He was interrupted by an older, scruffier man, also a Shukla. Harinder Shukla, 55, said: “Rajneetik parivartan kuch 10-15 saalon me aisa hua ki Hindu-Musalmaanon ke beech me rajnaitik roop se khaiyan bana di gai hain. The main political change in the last 10-15 years has been the creation of a deep cleavage between Hindus and Muslims.”

Harinder Shukla said the BJP’s “divisive politics” had led to even greater economic distress in the region on account of cow vigilantes, who had spread hate and fear by threatening and even killing people who sold cows. Now, hundreds of stray cows ate up farm produce, and there were not enough cow shelters, he said.

One such shelter with 400 stray cows rounded up was not too far from the Shukla village. In the centre lay a dead calf, with birds picking on carcass.

A dead calf at a cowshed in Bhadohi district’s Aurai block. Over 400 stray cows have been rounded up here, and the caretaker says 14 died in the last three months.

Modi supporters in the region were torn between admitting that there was a downside to the cow politics or denying that there was a problem at all.

When BJP candidate Bind was shown a photo of the dead calf, before he could answer, Rajendra Dubey, the BJP district president for the Bhadohi region interrupted: “Unse kya pooch rahey hain, woh abhi toh bicharey pratyashi huey hain…abhi interview mat kijiye. What are you asking our candidate, he’s just been made a candidate, the poor man. Don’t interview him just now.”

(Laul is an independent journalist and film-maker and the author of `The Anatomy of Hate,’ published by Westland/Context in December 2018. )

Courtesy: India Spend