New Delhi: Despite a four-fold increase in the number of women and children receiving supplementary nutrition under the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) programme in the 10 years to 2016, a large proportion of the poorest have not benefited, a new study has found.

Anganwadi worker Madhubala, 47, at a pre-school education class at an anganwadi held in a primary school in Kuiya village, Farrukhabad, Uttar Pradesh.

Women who were uneducated or from the poorest households had lower access to the flagship programme the study found. While the poorest households had the highest utilisation of ICDS services in 2006, their share became the second lowest in 2016, the study says, suggesting that the reasons could include poor delivery, difficulty of accessing remote regions, and social divisions such as caste.

Started in 1975, ICDS, the world’s largest scheme of this kind, provides nutrition and health services to all pregnant and lactating mothers and children under six years of age. In addition to take-home food supplements and hot, cooked meals, the programme provides health and nutrition education; health check-ups; immunisation; and pre-school care services at either government-run anganwadi (childcare) centres or at home.

The study, “India’s Integrated Child Development Services programme; equity and extent of coverage in 2006 and 2016”, co-authored by researchers the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), a research advocacy based in Washington D.C., and the University of Washington, US, will be published in the World Health Organization’s April 2019 bulletin.

Using data from two rounds of the National Family Health Survey conducted in 2005-06 and 2015-16, the researchers examined equity in ICDS’ expansion and the factors that determine the utilisation of its services.

Low to middle socio-economic brackets were more likely to receive food supplements, nutrition counselling, health check-up and child-specific services than both the poorest and the richest groups, the researchers found. Women with no schooling were also less likely to receive ICDS services than those with primary and secondary education.

“Even though overall utilization has improved and reached many marginalised groups such as historically disadvantaged castes and tribes, the poor are still left behind, with lower utilisation and lower expansion throughout the continuum of care,” said IFPRI research fellow and study co-author, Kalyani Raghunathan, in a statement.

Researchers found these gaps especially pronounced in the largest states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, which also carry the highest burden of undernutrition. While both states have shown improvements in 2016, they still fall behind national averages, suggesting that overall poor performance in high-poverty states could lead to major exclusions, the authors said.

Even in better-performing states, exclusion of the poor could be due to the challenges of reaching remote areas despite attempts to close district-wise and caste-based equity gaps, Raghunathan said.

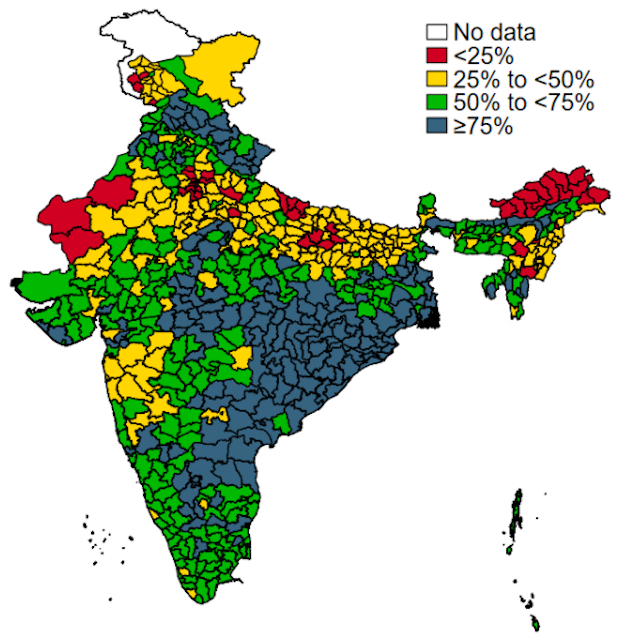

Proportion Of Children (6-35 Months) Who Received Food Supplements In 2016

Source: IFPRI

Coverage improves but the poorest still have less access

The study shows an increase in the number of beneficiaries of ICDS services from 2006 to 2016 in four key areas, along with an eight-percentage-point rise in the frequency of monthly supplementary foods provided to children:

- Supplementary food — 9.6% to 37.9%

- Health and nutrition education — 3.2% to 21%

- Health check-up — 4.5% to 28%

- Child-specific services — 10.4% to 22%

With the exception of Tamil Nadu, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand, the coverage of food supplementation during pregnancy and lactation was less than 25% in most states in 2006 but increased in almost all states by 2016. The greatest expansion was seen in food supplementation during childhood, which reached more than 50% coverage in Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Uttaranchal, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh.

The coverage of services has improved for the poorest group–from 11.7% to 34.8% for food supplement; 3.4% to 14.8% for nutrition counselling; 5.1% to 21.5% for health check-up; and 11.3 to 20.4% for child-specific services between 2006 to 2016.

However, barring the richest quintile–the top 20% wealth group–the poorest quintile had the lowest share in coverage of the four services in 2016. In 2006, poorest group had reported the highest share.

“Those belonging in the highest quintile may perceive ICDS as a scheme for the poor which is why they may opt out of the service,” said Purnima Menon, senior research fellow at IFPRI and co-author of the study, “It also could point out to the fact that the quality of the services would not be what they expect.”

Exclusion of the poorest could be due to difficulties with complying with programmatic conditions, the authors noted. But the most plausible explanation is poor service delivery in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

The two states are home to almost half of the poorest quintile (20%) of the Indian population and also have the lowest coverage of services, which adds up to the overall exclusion of the poorest quintile, said Menon. “Uttar Pradesh and Bihar have high fertility and high population so it’s likely they need more ICDS centres, and more financing to ensure full-scale delivery of all services,” she said.

When the researchers analysed the differences between different caste groups in accessing services, they found that in 2006, scheduled castes and scheduled tribes were twice as likely to receive supplementary nutrition as other groups, but in 2016 the differences were smaller.

Of all castes, Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes utilised ICDS services the most, the study said. In Odisha and Chhattisgarh, with large tribal populations, efforts to strengthen the system seem to have worked, as have efforts to focus on tribal areas as part of the state health mission in Maharashtra, the authors said.

Scheduled Tribes are among India’s poorest with 45.9% falling in the lowest wealth bracket, IndiaSpend had reported in February 2018.

Mothers with no schooling received fewer ICDS services

While only 34.7% of uneducated mothers received food supplements, 43.7% of those with primary education and and 43.8% of those with secondary education did. This trend was visible across services, although those with the highest category of education also had lower access.

“The women with no education may intersect with the poorest quintile which is predominantly in UP and Bihar, which could explain their poor utilisation but we are yet to analyse this,” Menon said, adding that there is much to be explored in further analyses.

ICDS: From patchy start to universal coverage

ICDS services were patchy throughout the early 2000s. A 2005 World Bank report said that since children in the crucial development age-group of 0-3 years were not getting enough attention, maring the programme’s effectiveness. Also, ground-level staff lacked adequate training, political commitment was missing, and the programme failed to reach out to the poorest households and the lower castes.

Another 2006 study found only 6% girls aged 0-2 years and 14% aged 3-5 years received supplementary nutrition despite 90% of their villages having an ICDS centre. These led to reforms from 2006 to 2009–more funds and provision of supplementary nutrition in a rights-based framework.

In 2006, India’s Supreme Court ruled that the programme was to be offered universally. Soon after, the government expanded its services across India, with a goal of ensuring about 1.4 million centres across the country. Today, ICDS serves about 82 million children younger than 6 years and more than 19 million pregnant women and lactating mothers.

Why ICDS scheme needs more attention and support

Previous studies have shown that greater coverage and utilisation of services leads to improvement in health–for example, this 2015 study showed that girls who received supplementary nutrition grew taller than their peers.

However, there has been a decrease in funding for ICDS in recent years and since it is a demand-based scheme, much of it is blamed on low demand from beneficiaries.

Although the present study shows an overall improvement in access, another story with a shorter time-frame shows the number of children from 6 months to 6 years who received supplementary nutrition fell by 17% from 2014 to 2019 from 84.9 million to 70.5 million, and of pregnant and lactating mothers reduced by 13% from 19.5 million to 16.9 million, according to a 2019 budget brief by the Accountability Initiative of the Centre for Policy Research, a think-tank.

The number of beneficiaries fell across the country but was noticeably more in poorer states such as Bihar (53%) and Uttar Pradesh (25%). The share of anganwadi services in the overall budget for the ministry of women and child development fell from 89% in 2014-15 to 68% in 2019-20.

“While adequate funding is definitely an issue, the IFPRI study points out the fact that ICDS services are not reaching the poorest quintile and that means poor don’t know about the services or don’t find them convenient to avail [of] due either to access gaps or social norms,” said Avani Kapur, director, Accountability Initiative. “This means there is need for more home visits, behaviour-change communication, filling up [of] vacancies of CDPOs [child development project officers], lady supervisors and training of anganwadi workers,” she added.

The wages of frontline anganwadi workers were increased from Rs 3,000 to Rs 4,500 per month from October 2018, which Kapur said is a good move, adding that providing transport facilities to women supervisors to reach remotes tolas (hamlets) could also help.

(Yadavar is a principal correspondent at IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.

Courtesy: India Spend