Our work is more about an attempt at playing around with the popular imagination, rather than an ode to an original. It’s not so much about nostalgia for great art as much as working with ideas of iconicity, recreating through digital technology and performing our fantasies.

‘The Girlfriends’ by Gustav Klimt re-created by Samira Bose and PakhiSen featuring Sawani Kumar and LumriJajo

In 1925, Mexican painter Frida Kahlo lay in bed,immobilised and in terrible pain. Kahlo was convalescing from a tramcar accidentthat had left her in a full-body cast. Adding as it did to a long history of illness and disability, the accident would deeply alter her sense of self. It would also prompt thecreation of ‘Self-portrait in a Velvet Dress’, the first in a series of works through which she would turn her gaze inwards. The self-portrait was significant to Kahlo because, in her words, “I am the person I know best. I paint my own reality. The only thing I know is that I paint because I need to…”She chose the self as muse because it was a subject both familiar and deeply significant.

Several oceans away, a contemporary of Kahlo’s – Amrita Sher-Gil – was conducting a similar exploration of the doubleness of identity for the artist-muse. For Sher-Gil, her self-portraits allowed an examination of heritage and sexuality–her work moving between depictions of self as Western and Indian, child and woman. Both artists sought to present themselves on their own terms, creating paintings that were frank, compelling, and sometimes unsettling. What does it mean, they seemed to ask, to turn our gaze upon ourselves?

This question of female representation is one that artists PakhiSen and Samira Bose attempt to answer. In doing so, they seek not only to create portraits of their own but also to respond to the tradition of portraiture that they have inherited. Sen and Bose (charmingly contracted to BOSEN) blend contemporary muses with images from across history – casting friends and collaborators in recreations of great art. So far, the duo has tackled Mughal miniatures, and the work of Gustav Klimt and Amrita Sher-Gil. Their images are painstakingly constructed, deploying a technique that marries a rich vocabulary of textile and print with a striking attention to detail.To better understand how they speak to and alongside the women they re-imagine, I interview Samira Bose and Pakhi Sen.

BaniThani as Radha, ca. 1750, painted by an artist by the name of Nihâl Chand, Marwar School of Kishangarhfeaturing Asmi Sharma, re-created by Samira Bose and PakhiSen

I know that the two of you have been friends for the longest time. The relationship between collaborators can have commonalities with as well as distance from the relationship between artists who happen to be friends. Can you tell me about what prompted your collaborative journey?

If we think about it, we could trace our journey to discussions we started having very early on (at 16), when we started engaging with politics, feminism, particularly while trying to navigate and cultivate our “personal style” choices that drew on popular culture. A lot of these conversations are embarrassing to think about in retrospect, but they laid a kind of collaborative foundation. In that sense, staying friends through different “aesthetic phases”, traveling together, constantly sharing our discoveries and inspirations with each other really forms the base of why we can collaborate as artists. Over the last few years, we developed our interests in art from slightly different angles, depending on where we studied or where we traveled. I think an interesting time for us was also when we traveled across Ladakh together for a project in 2015. After that the desire to collaborate together was actually impulsive and instinctive, just the fact that we can sit for hours and hours after all these years and talk about everything under the sun means there’s a lot of collective energy that we can channel creatively. Our standpoints are slightly different, but in that sense complimentary, while I (Samira) tend to approach things from a more theoretical point of view, Pakhi’s is more design oriented. But we are both very impulsive. We open to each other’s strengths and try to work with them. There’s basically a lot of energy and enthusiasm and synchronicity because we’ve been friends through incredibly strange young adult years.

On the topic of collaborations, I feel as though your pieces are not just based on the dynamic between the two of you but also emerge from a joint act of creation between a larger group of women – your muses, your models. Do you see your work like this?

Yes, most definitely. Our work is actually entirely a collective process. It’s interesting to see how this plays out in terms of group dynamics, but we have been lucky that our friends/associates are so understanding and help out in a very tangible way outside of performing for the photographs. Our workspace is Pakhi’s living room, and we create these photographs in a pretty casual setting, we try to put on music and laugh around and costume together. It’s funny, because we always enjoyed the homosocial space of getting dressed together for parties. In some ways, this is an extension of that.

We are all involved, Pakhi and I just give the creative direction, as it were, but the entire space is charged by all the women that participate.

‘Self Portrait (1930)’ by Amrita Ahergill,re-created by Samira Bose and PakhiSen featuring Samira Bose

Having grown up chiefly in Delhi, do you think your work has a certain sense of place? Has the city informed your aesthetic in any way?

That’s a really interesting question, and we haven’t thought about it exactly. Growing up in a city that’s inherently diverse and cosmopolitan definitely affects the way in which we open ourselves out to artists that span the globe as much as they span history. Both of our parents actually come from entirely different parts of the country, and in that sense we do feel like we are “Delhi-ites” because we don’t feel regionally committed to any state or cultural background, we are actually a mish-mash. And rather than an aversion to this lack of belonging, we actually find a kind of anarchic potential in being able to posit ourselves in varying aesthetic structures. Perhaps another thing that being from Delhi gives us is a sense of confidence and privilege to be really loud about what we do, and put ourselves out there. That’s definitely a Delhi characteristic.

You’ve said that you feel a personal affinity for Sher-Gil’s work. What relevance do you think her art and politics have in contemporary Indian gender-politics?

For us, personally, our attraction at one level was entirely to her masquerading style and confidence. Politically, it’s because she stares back, she’s incredibly daring. Of course, coming from a privileged background and being a third-culture woman, she was able to push boundaries and buttons but that does not deny her experimental defiance. To put it quite simply, there’s clearly a very strong charge in contemporary Indian gender-politics, with protestors taking to the streets against institutional restrictions or using social media to start movements against conservative comments by politicians. Even in popular Indian cinema, there’s a sense of anger as well as bold brazenness that’s starting to make its way despite the numerous obstacles (From Queen to Lipstick Under My Burkha). Sher-gil and her work embodied a lot of these elements.

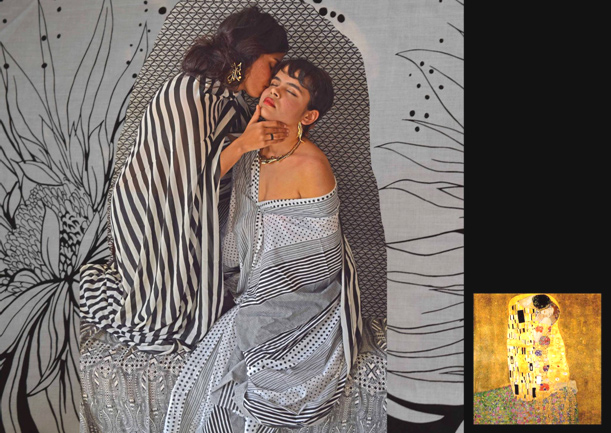

‘The Kiss’ by Gustav Klimt, re-created by Samira Bose and PakhiSenfeaturing Shrishti Jain and GulshanBanas

Your work makes heavy use of Indian textiles and prints. Could you tell me about the importance of this dimension of your work? At a time when the handloom industry is in financial threat, what does your project hope to do?

This is one of the central dimensions of our work. It’s as much about making prints clash and mix as much as it is about using a wide variety to make a statement. The background varies though. While in the Sher-Gil project we attempted to use more handlooms and vegetable dyes, and in this context we hoped to encourage the handloom industry and handicrafts. However, in the Klimt project we used a lot of digital prints and mass produced fabric from the markets. Our statements about prints and textures aren’t uni-dimensional in that sense, we are interested as much in the way that prints work together in mass produced, synthetic material. In the Miniature project, we attempted to archive our heirlooms (one lehenga is a 100 year’s old and Pakhi’s great-grandmother’s) and it’s a kind of living-archive narrative that we are trying to weave to document these garments that are literally disintegrating.

‘Originality’ is often emphasised in art and literature. How do you think your work interacts with this narrative?

This authorship and originality/authenticity discourse has really been a raging debate for a while. Contemporary art has kind of even moved on beyond it, at a time when we can access images and prints at the click of a button, it’s difficult to find points of origins in any case. Our work is more about an attempt at playing around with the popular imagination, rather than an ode to an original. It’s not so much about nostalgia for great art as much as working with ideas of iconicity, recreating through digital technology and performing our fantasies.

Your work moved from Sher-Gil to Austrian Gustav Klimt, which is a significant geographical and temporal shift. What informs your choice of muse?

Well, the immediate decision comes from an impulse, it’s actually plays out in a very visual way in our mind. We actually like such a wide variety of artists, that it’s hard to even say how we narrow down. It just feels right. And then we deconstruct the elements. Like I said before, we are privileged to be able to access a lot of art across time and space (particularly thanks to the internet), and we rely a lot on our aesthetic instincts in what we get attracted to, particularly in context of our photo-performances. This might not hold true when we think about the work we do in university.

To explore this question of muse further – all three of your series seem to bring together more distant artistic moments and contemporary models and treatments. What do you believe is uniquely valuable about this choice?

We actually worked with Indian miniatures that span Mughal, Rajput and Deccan styles. I don’t know if we want to use the word valuable, but let’s go with unique. We are interested in this context with the intricacies and details involved in miniature painting. Sher-Gil was about performing a personality, Klimt about form and the Miniature project is about detail and a mythic imagination. We used the more iconic paintings of women and also investigated stories and anecdotes about the different characters. It’s difficult to articulate this in its exactness but we also want to play around with the idea of the “grand” and the “royal” in history by making the performance contemporary, using our current aesthetic and digital tools. This is also an archival project, so we are using paintings that are used for historical archiving in a personal context – to archive and document our own heirlooms and objects from around our home.

Given that Mughal miniatures often display a certain synthesis between Islamic forms and Hindu iconography, do you think they have a particular significance today?

They most definitely have a significance – particularly since names of roads are being changed, our school textbooks are being re-written, we are designating the “foreign” and the “other” in the most ahistorical fashion. We are trying to say that we are a synthesis of all these different cultural backgrounds and aesthetic sensibilities – just like the miniature paintings are quite literally a synthesis. We want to embrace this diversity, albeit being critical, but we most definitely don’t want to celebrate one over the other to propagate a homogenous idea of this so-called nation.