Nandita Das is an internationally acclaimed Indian filmmaker and actor. Ms. Das, a recipient of ‘Ordre des Arts et des Lettres’, has served on the jury of Cannes Film Festival. She is the first Indian to be inducted into the International Hall of Fame of the International Women’s Forum in Washington. She also happens to be one of first few people in Bollywood to speak against the obsession with lighter skin, her campaign ‘Dark is Beautiful’ garnered international attention to a widespread issue.

In an exclusive interview, Nandita Das talks to Ujjawal Krishnam about her film ‘Manto’ and beyond.

When did you first think about making a film on Saadat Hasan ‘Manto’?

For years I thought of making a film based on Manto’s short stories, even before I made my directorial debut, Firaaq. But it was only in 2012, during Manto’s centenary celebrations when a wide variety of his works were translated, and much was written about him, that I delved deeper into his essays which helped expand the idea beyond his stories. The more I read and researched, the surer I became of the relevance of Manto in our times. Almost 70 years later, our identities lie inextricably linked to caste, class, race and religion, as opposed to seeing the universality of human experience.

Manto shows us a mirror to our fears and prejudices. I don’t think I ‘chose’ to make the film. I felt compelled to tell the story. It took me 5 years to feel equipped, both emotionally and creatively, to tell this story that so needed to be told. The emotional, spiritual, creative and socio-political journeys of making this film have impacted me indelibly and profoundly and made me a different person.

‘Manto’ has received much critical acclaim, however people aren’t exactly thronging theaters to watch Manto the way they would respond to an average mainstream movie. Do you feel that such movies are not meant for commercial gain?

Films like Manto are constrained by the presumptions of those who are responsible for marketing and distributing films. There is a clear dissonance between what is seen as ‘creative’ vs. ‘business’ in terms of the spending on publicity and advertising and on the number of screens and the show times. While this tussle between a director’s passion for a film and the reality of business is eternal, it is perhaps worth a debate in today’s world.

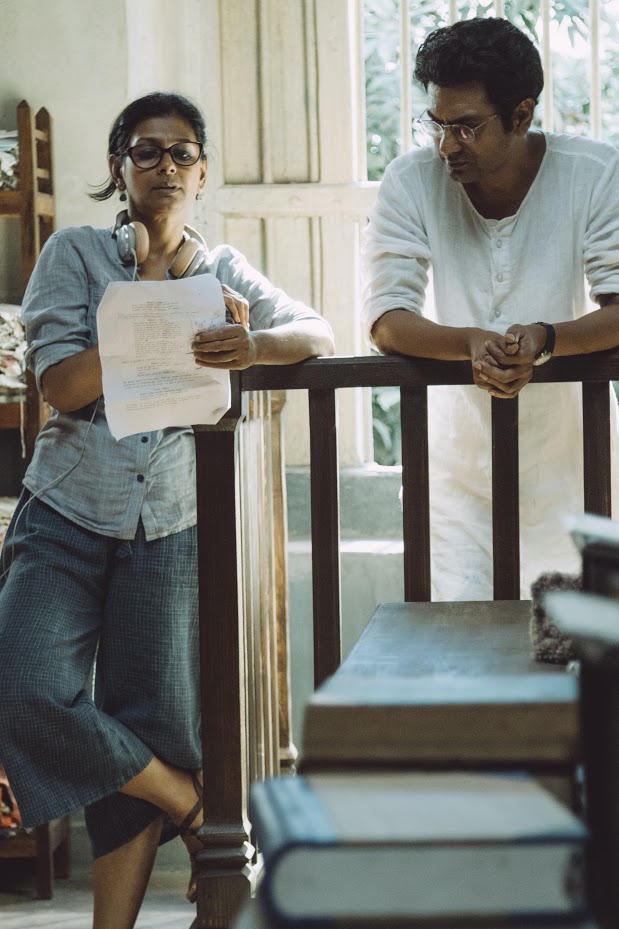

Nandita and Nawaz, Courtroom

Manto, is perhaps a good example of how in-built biases affect the potential of a film that is not classified as a “Bollywood” film. These are the ones that get labelled as niche films. This has big consequences. This impacts the number of screens – a mid-sized release for ‘Bollywood’ is about 2000 screens while Manto released in less than 500. Cinema is the primary form of entertainment in India and will continue to be so because of many theatres, growing reach of TV channels and new digital platforms. However, from my perspective as an independent storyteller, it is still difficult to make films that do not follow the commercial template. The diversity in stories that independent cinema could bring is still not prevalent due to economics interfering with art.

How do you look at gender when you write?

I have always believed that gender sensitive films do not automatically have to be women-centric, more importantly, the representation of women needs to reflect the diverse reality. I have often been asked that given all my engagement with issues of gender, why are neither of my films women-centric? For one, women are impacted by all things in the world just as men are. And therefore, I have chosen to respond to issues that concern me. Secondly, in both films, the characters of women need to be judged not by their screen time but by their layered portrayals. In fact, the same goes for all characters – to make them believable, they need to be “whole” and have some kind of a journey or a graph.

In Manto’s times, women didn’t occupy as much of the public space but he was surrounded by them in his personal life. Whether it was his wife Safia, his daughters, his sister – Nasira Iqbal, or his friend and fellow writer, Ismat Chughtai, they all are important to the story and have multiple facets in their representation.

Indian Cinema is infamous for its misogyny, what is your take on it?

While I have not been a part of mainstream Bollywood, I have done over 40 films in 10 different languages. And I know first-hand that misogyny and sexism are rampant in the film industry, in India and beyond. I think we are all very happy that what was being said behind closed doors and in whispers is being heard because of movements like #MeToo and Equal Means Equal. Many powerful women are using various platforms to speak out and keep up the momentum. However, in India, there is still a deafening silence primarily because women feel more vulnerable in a patriarchal society and a male dominated industry, and fear being ostracized and further attacked. When a project is submitted, the question is still asked – who is the hero? An A-list actress will never have an A-list actor playing opposite her if she’s playing the lead. While the opposite happens all the time. These things take time to change.

Manto with daughter in Apartment

Female actors are still stereotyped in their portrayals – to be perpetually good-looking (read sexy, if they are young, which they invariably need be) and their careers are still much shorter than their male co-stars, who at 50 can play college boys. Having said that, definitely more and more women are now behind the camera so there is a little more representation and diversity in filmmaking. It is still far from enough, though. Stories exploring issues more central to women and that depict women and their diverse realities are increasing. But every other film still focuses on ‘sexual freedom’ by showing female characters in sexy clothing – a continued pandering to the male gaze. Quoting a journalist reviewing one such film, “(the women) remain slaves to their vanity kits and costume designers.”

‘Manto’ appears more a charity project in good faith than a commercial movie. Do you look forward to make a commercial blockbuster film coupled with the null coefficient of societal relevance?

I don’t even watch those films, so acting or directing them doesn’t appeal to me. I am not judging those who watch hardcore commercial films or act in or direct them. I am all for freedom to choose. I feel there should be enough space for diverse stories, which is not the case, as often commerce interferes with art. Somehow, I feel it’s more in our country than others. Considering we make a 1000 films a year, they don’t reflect the diversity that exists in our country. I will continue to pursue projects that interest me and allow me to share my concerns and connect with the world around me.

How do you manage to provide comprehensive detailing of the issues without inviting any trouble from self-proclaimed guardians of culture?

Whether it was for films I acted in like Fire or Bawandar, or my directorial debut, Firaaq, I have certainly offended the self-appointed custodians of culture and been criticized for my choices of subject matter and the way I chose to portray them. Films that do not follow the conventional big-budget template are challenging everywhere in the world, but we in India face the additional challenges of arbitrary censorship and these aforementioned elements who exercise their veto against anything that challenges their cultural and social norms.

However, whilst Manto’s writings may have been controversial in his time, and may remain so in some spaces even now, there is nothing controversial about his own life. At least 71 years later, we should be able to celebrate him and his humane ideas, without hesitation.

Both your films tackle social issues and are set during periods of great upheaval and turmoil, why is that?

I am not a professional filmmaker and for me films are a means to an end. Making a film requires so much time, energy and money that I would want to use this powerful medium to share my pressing concerns. Firaaq and Manto were born out of my need to respond to the growing violence and prejudice in India, but were manifested through very personal stories. In the end, it is only human stories that move us.

Manto and Safia, reading letters in Lahore Apartment

Being in the public space, I believe my work has some influence, even if it is only to an extent. But with this influence comes the responsibility to be a voice for the voiceless. Not in a patronizing way. I see myself simply as a catalyst. The way we view our society, relationships and people in films will somehow find its way into how we see them in our daily lives. This is what makes films powerful. I don’t like being didactic or preachy. No one wants to be told; but sharing stories can impact how we respond to people and events.

I feel that Manto’s story is more about a writer’s conviction and courage, and angst and loneliness. I feel there is a Mantoiyat, in all of us – the part that wants to be free-spirited and outspoken. And it is with this intent that I have made Manto.

In Firaaq, you looked at the Gujarat riots which saw some of the worst communal violence of contemporary India. In Manto, are you again looking at a period of profound and deep violence, what draws you to this?

What intrigues me is how violence impacts us all, however far we may think we are from it. I prefer to show individual and intimate personal stories, like Manto did, to reflect reality instead of pointing fingers at what we might think are the “villains” of the story. That would, in fact, further polarize us instead of triggering conversations and helping us introspect. I personally don’t like to see violence in films and therefore while both the films are set in times of great violence, there is none in the films. What is interesting, for me, is to see what violence leaves behind and how fear manifests because of it. Manto added another layer to this exploration – the best of us have shadows and the worst of us can be redeemed.

The film comes at a time when the relationship between Pakistan and India is tense. Do you think that increases its relevance?

I think the role of art and cinema is to build bridges. When there is political tension, they can become the means to bring people closer, lessen prejudice and trigger conversations. Whenever I have been to Pakistan, I find people in admiration of our democracy, diversity, art, culture and in particular, cinema. Of course, we need to fight terrorism, governments that encourage it instead of stopping it, but we also need to have the wisdom to separate the people from those governments. Art can in fact become the balm to our common wounds.

Irani Cafe

Do you entertain criticism of your work?

For more than 18 years, I have chosen not to read what has been written about me or my work. My first brush with public reaction was after I acted in my debut film, Fire. I remember getting a wide range of reactions – from people who praised my bold performance, to those who accused me of trying to convert all women into lesbians! One morning, reading the most ridiculous interpretation of the film, I decided I will read no praise, no criticism. It has kept my sanity and helped me take myself less seriously.

With all the challenges that came with this film, I am far more “zen-like” today than I have ever been. And now I feel, for the first time in those 18 years, I am able to read a little of the various responses the film is garnering. I am overwhelmed by the way people have connected with the story, its characters, and the journey that I have lived with for so long.

What message do you have for young film-makers? Please tell us about your future plans?![]()

As of now, I am still on the Manto journey. The film has been invited to the Singapore South Asian International Film Festival, Busan International Film Festival and BFI London in the coming month, among others thereafter. I am also working on a book about my journey through this film, so I am not working on anything new as of now. But I have already begun to get projects, which is very encouraging. I have found three scripts that I am quite interested in, to direct. In fact, I have received several projects for acting as well. But I do look forward to taking a break, spending some time with my son before I move on to my next project.

Photos: Team Manto