The incredible lightness of seeing: Exploring humour and activism in the art of Adrita Das

Avani Tandon Vieira

Adrita Das

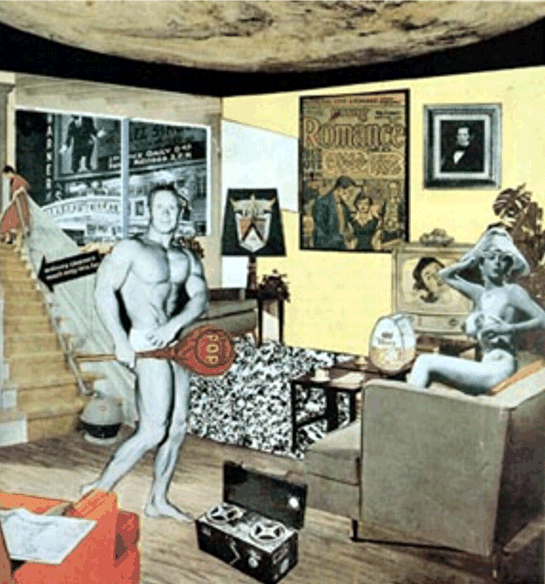

In 1956, the Whitechapel Art Gallery in east London organised an exhibition called This is tomorrow. Coming a decade after the end of World War two, the show soughtto imagine the future of post-war Britain, inviting artists to present their visions for the nation that would be. For British artist Richard Hamilton, this future presented itself as a collage, intriguingly titled Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?

For his contribution to the exhibition, Hamilton combined disparate images from American magazines to create a piece that was jarring in its artistic choices. In a living room from Ladies Home Journal, he placed a body builderand a burlesque dancer undera picture of planet earth. Around them was a strange mixture of objects – tape recorders and televisions, photographs and portraits. The sense of congestion that this generated was deliberate, pointing to the intensely consumerist spaces that were coming to characterize the Britain he experienced. Hamilton’s piece would become iconic for the pop-art movement, not just for what it said, but also how it chose to say it – drawing from distinct visual registers to create what was almost a new language of images.

Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?

Richard Hamilton, 1956

Over fifty years from Thisis tomorrow, the visually saturated environments that we experience continue to offer opportunities for seeing, and building, anew.

This is what Mumbai-based artist Adrita Das, of Das Naiz, accomplishes through her humorous, multi-layered representations of the places and times we live in. Das’s collages present selfie-taking Hindu Gods alongside Mughal queens at Black Lives Matter protests.

Her gifs imagine ‘60s models in the throes of existential angst and dictators in psychedelic rage, flitting between political commentary and humorous musings. Her work merges the old and the new, the sacred and the everyday, suggesting that the newness of unfamiliar visual meetings holds immense potential for querying our todays and tomorrows.

To understand the politics of her medium and process, I speak to Adrita Das about the role of the artist as activist, censor, and observer.

Adrita Das

What I find striking about your work is how central humour is to the whole process. How do you imagine the role of humour in activism?

I have been asked about why I use humour in almost everything that I make. You know, I don’t particularly start out trying to make someone laugh. If you look deeper into a lot of my work, the core of it is not funny at all- it is in fact, quite grim, similar to the reality of our lives. Maybe we find it funny that we are placed in such complex situations that have no answers. Humour is hence most valuable to activism; it takes away the burden of reaching a conclusion while also offering a more nuanced perspective.

Subversive art and humour are quite similar in the way they function. The audience is instantly reminded of institutions thatsubconsciously control him, such as the government, surveillance, religion, ideology but at the same moment of them looking at the subversion, the barrier between them is lifted. We often cite humour as an excuse for these when in fact, no one needs to apologise to appreciate subversion and dissent.

I’ve noticed that gifs seem to be rather central to your artistic practice. What draws you to them as a form?

Since I grew up learning and practising art at the same time that the internet exploded, it became an integral part of my process. At a time when I grew weary of the idea that all art must be made to- beautify the world/ make it a better place/ bring social reform (as taught to us in schools), post-internet art brought along with it a kind of meaningless-ness that I started to grow fond of. Of these, GIFs were easy, small loops of unpredictable imagery that could easily lift someone’s mood, effortlessly making their way into people’s lives and subconscious when even the most elaborate of art forms could not move them. This is what drew me to create and explore GIFs, especially with an Indian subtext.

Contemporary protest culture is very much a culture of visual engagement – whether you’re talking about posters for the Women’s March or more locally, the posters for #notinmyname. Why do you think visual cues have become such a central part of activism?

Visual engagement has always been a core chunk of activism, the examples of which can be seen throughout art history. (For example the ways surrealistic art was born as a tool against fascist powers under Mussolini.) However the internet and digital world has changed the visual landscape of activism. Creating and adding to this landscape is now more accessible than ever, with almost everyone well versed with instant photography and the art of hashtagging. We are probably the first generation that has the ability to effectively document, archive as well as curate this activism and visualising this data has become more important than ever.

Hanuman on Sundays, Adrita Das

A lot of your work integrates images from across periods, cultures, and religions – often almost irreverently. Could you tell us about what this technique helps you achieve?

As is the case with most subversive art, I too, take up imagery that is iconic. It doesn’t bother me to not do enough justice to the original context of the imagery, such as the ones in the Last Cupcake. What comes out of it organically is more important to me. There are however, exceptions where the context of what I’m using to create the collage is at the forefront but in general I have found people to always question the purpose of art, when in fact I don’t see that as enough motivation for creating work. What comes after it has reached an audience and how they react to it, is the purpose.

Adrita Das

Your selfie Gods series was very well received and even though it was so popular, people didn’t seem offended by it. At a time when it seems very easy to upset people through the use of religious or cultural iconography, how do you see the role of artists?

Although most people took to it lightly, there were a significant number who were quite offended by it. To them, it felt like I was only belittling Hindu Gods and Goddesses which was a baseless argument since I used murals, paintings and imagery from Iran, Japan and even Mughal paintings.

I think there is a fine line of humour that one must self-assess and then take a stand- if they are willing to stand up for it, then it should be out there. I do think at artists censor most work themselves as they are often quite critical of what would be well received and what not. At the end of the day, I feel that I do want to make jokes at the expense of others and in a way that is altruistic- and so I didn’t spare anyone, including myself.