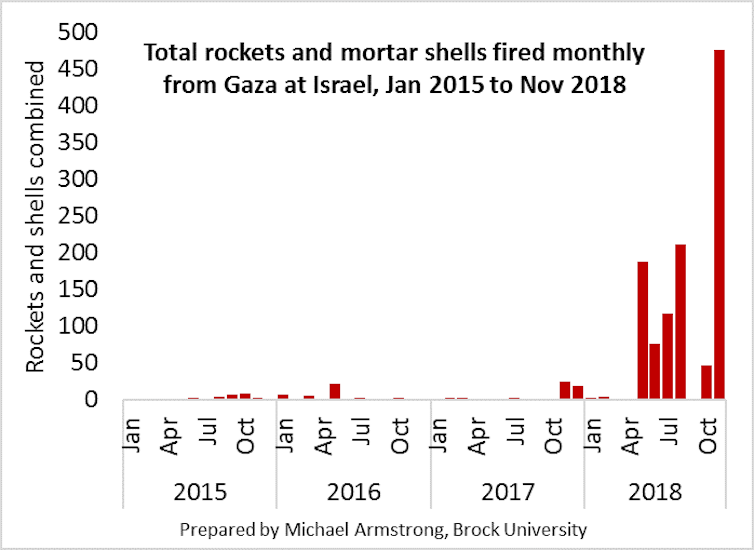

The barrage was the largest since 2014. It brought Gaza’s year-to-date total to 1,124 rockets and shells fired.

Israel responded by bombing 172 Hamas and Islamic Jihad targets in Gaza. About 15 Palestinians died and several buildings were flattened.

The exchange of blows was surprising in one sense: thanks to Egyptian mediators, the two sides had seemed close to negotiating a truce. That’s despite their seemingly incompatible demands regarding military security, economic activity, and prisoner exchanges.

But in another sense, the abrupt switch from ceasefire to gunfire was predictable. Both Israel and Gaza have been relying on brinkmanship in dealing with each other. And that bargaining strategy always poses risks that the situation can slip out of control.

Brinkmanship hits and misses

Fortress Morro-Cabana in Cuba. The exhibition of the Soviet weapon devoted to the memory of the Cuban Missile Crisis. KKulikov/Shutterstock

Brinkmanship is a powerful but risky strategy for resolving disputes. The United States used it successfully during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. It forced the U.S.S.R. to back down and avoided a nuclear war. But not before the Soviets shot down an American spy plane and nearly torpedoed a warship.

The strategy was less successful during America’s 1981 air traffic controller strike. During that labour dispute, neither the controllers’ union nor President Ronald Reagan would give in. When Reagan ultimately fired the strikers, 11,000 lost their jobs and airline flights were disrupted for months.

Mutual threats

The Israel-Gaza situation similarly involves each side using brinkmanship to pressure the other. Like the historical examples above, this one displays several key features.

First, if the two sides don’t eventually reach agreement, they’ll suffer a disaster both wish to avoid.

Regarding Israel and Gaza, both want to avoid a full-blown war like 2014’s Operation Protective Edge. If one erupted, Israel’s interceptors and civil defences would limit its casualties from Gaza’s estimated 20,000 rockets and shells. But such a conflict would still cost its economy several billion dollars, like Protective Edge did.

Israeli airstrikes and artillery would meanwhile devastate Gaza’s already-weak infrastructure. A ground invasion might even topple the Hamas government.

Inching toward disaster

A second feature of brinkmanship is both sides deliberately inch toward that mutual disaster. Each proclaims its determination and willingness to approach the brink. Each hopes the other will concede first.

Gaza firepower escalations demonstrate this progression. Militants there began using to burn Israeli crops in April. In May, they fired 188 rockets and shells, the first significant barrage since 2014.

Explosives-laden balloons joined the fire-carrying ones in June. In July, sniper fire killed the first Israeli soldier near the border in four years. More rockets have since followed.

Diagram prepared by author, based on Israeli Security Agency reports. The November 2018 count is based on news reports up of Nov. 20. Michael Armstrong

Israel’s responses intensified correspondingly. It initially dealt with flaming kites by intercepting them. In June it began firing warning shots near the kite-launching teams. It started targeting them directly in July, resulting first in injuries and then a death.

Airstrikes, such as the 50 tons of bombs dropped July 14, were initially used only after rocket attacks. But they became common retaliation for kites too.

Losing control

Brinkmanship’s third feature is a growing risk of losing control. Both sides may fully intend to stop short of disaster. But they know it’s increasingly likely they’ll accidentally slip over the brink.

This has happened several times in Gaza. While Hamas rules Gaza, it has limited control over Islamic Jihad and other militant groups. Islamic Jihad reportedly started the May rocket barrage, with Hamas only belatedly joining in. A sniper reportedly affiliated with “rogue” militants wounded an Israeli soldier near the border in July. And in October, an accidentally launched rocket destroyed an Israeli home.

Such risks are amplified by hair-trigger retaliations that allow little room for error. After July’s rogue sniper attack, Israeli forces promptly attacked Hamas installations and killed three Palestinians. Gaza militants responded by firing nine rockets. That triggered seven more Israeli airstrikes. The entire escalation cycle took only a day.

Israeli spies discovered

Israel’s control has slipped too. In August an army patrol mistook a Hamas military exercise for a sniper attack. The patrol’s gunfire killed two militants. And last week’s violence began when Israeli spies were discovered during a mission in Gaza; one was shot dead.

Israeli politicians have also stumbled. Facing public frustration with the conflict, Israeli politicians have competed to sound the most belligerent. Even the minister of education has called for war.

Such tough-talk may have seemed like mere posturing. But when the Israeli government agreed to resume the ceasefire last week, the defence minister resigned in protest. (That gave Hamas cause to celebrate.) The country’s coalition government consequently may collapse and trigger early elections.

For the time being, Israel and Gaza have resumed their shaky ceasefire. But absent some miracle, the violent instability seems likely to continue, leaving the two sides only one incident away from war.

Michael J. Armstrong, Associate professor of operations research, Goodman School of Business, Brock University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.