The US-Israel war on Iran has triggered a sharp surge in anti-Muslim hate online. This data analysis by the Centre for the Study of Organised Hate (CSOH) examines Islamophobic discourse, documenting patterns of dehumanisation and incitement post the war attack on Iran launched by the US-Israel combine on February 28.

Since the start of 2026, harmful content targeting Muslims across social media platforms has escalated at an alarming pace. For much of January and February, Islamophobic posts maintained a steady and persistent presence, continuing the deeply hostile climate that has built since the start of the Israeli war on Gaza in October 2023.

The onset of the US-Israel war on Iran on February 28, says the study, has accelerated this trend sharply, sending Islamophobic content targeting Muslim Americans to new extremes.

Political rhetoric has compounded the crisis. Senior Trump administration officials and some members of Congress have framed the war in overtly religious terms, drawing on Christian nationalist narratives, and inflaming anti-Muslim hatred. Secretary of War (a term coined to replace the more accepted, Secretary of Defence) Pete Hegseth even described Iran as driven by “prophetic Islamic delusions.”

The Military Religious Freedom Foundation (MRFF), a US watchdog group, has reported receiving complaints that military commanders told service members the war with Iran was “all part of God’s divine plan” and suggested it would “cause Armageddon.”

House Speaker Mike Johnson, while referring to Iran, stated that “we’re the Great Satan in their analogy and their misguided religion.” Muslim civil rights groups have condemned such language as dangerous and inflammatory. Political leaders at the highest levels framing a military campaign in language that indicts an entire faith and draws on Christian nationalist rhetoric contributes to an environment in which Muslims and those perceived to be Muslim become targets of suspicion, hostility, and violence.

On March 1, a mass shooting in Austin, Texas, further intensified the online discourse. A gunman with a reported history of mental health issues opened fire at a bar, killing three and wounding fifteen. The shooter was reportedly wearing clothing referencing Iran and Islam.

The combined effect of the US-Israel war on Iran and the Austin shooting resulted in an explosion of anti-Muslim content across social media platforms.

An Analysis of the Data

To assess the scale of Islamophobic discourse online, the Centre for the Study of Organized Hate (CSOH) analysed posts on X (formerly twitter) using a comprehensive query designed to capture language associated with dehumanisation, incitement, and exclusionary rhetoric targeting Muslims.

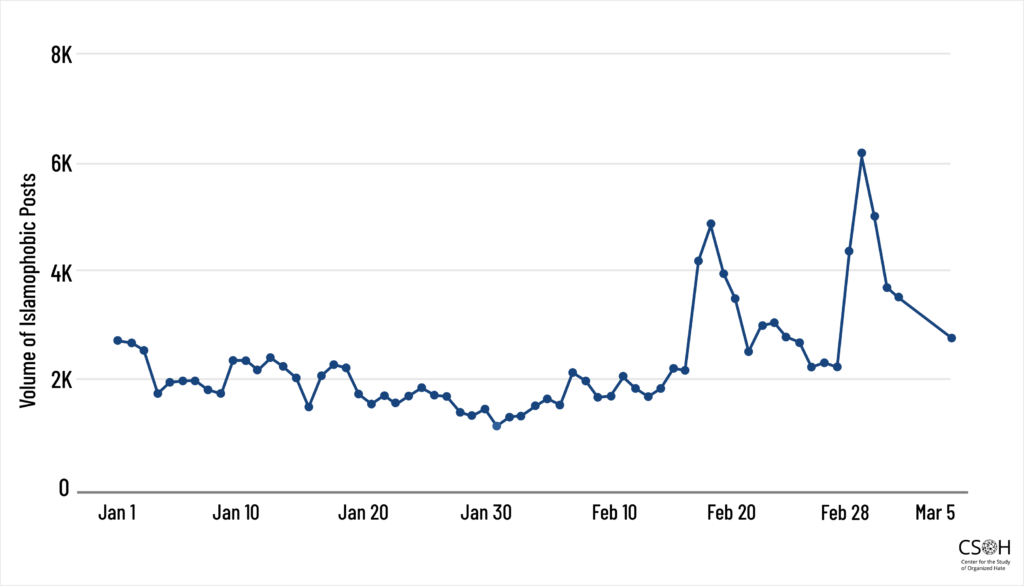

The dataset includes original posts, quote posts, and replies containing Islamophobic content from January 1 through March 5, 2026. The data reveals a sharp spike beginning on February 28, the day the US-Israel war on Iran began.

Between February 28 and March 5, a total of 25,348 Islamophobic posts targeting Muslims were recorded on X.

Figure 1: Volume of Islamophobic Posts on X (Original Posts, Quote Posts, and Replies), January 1 – March 5, 2026

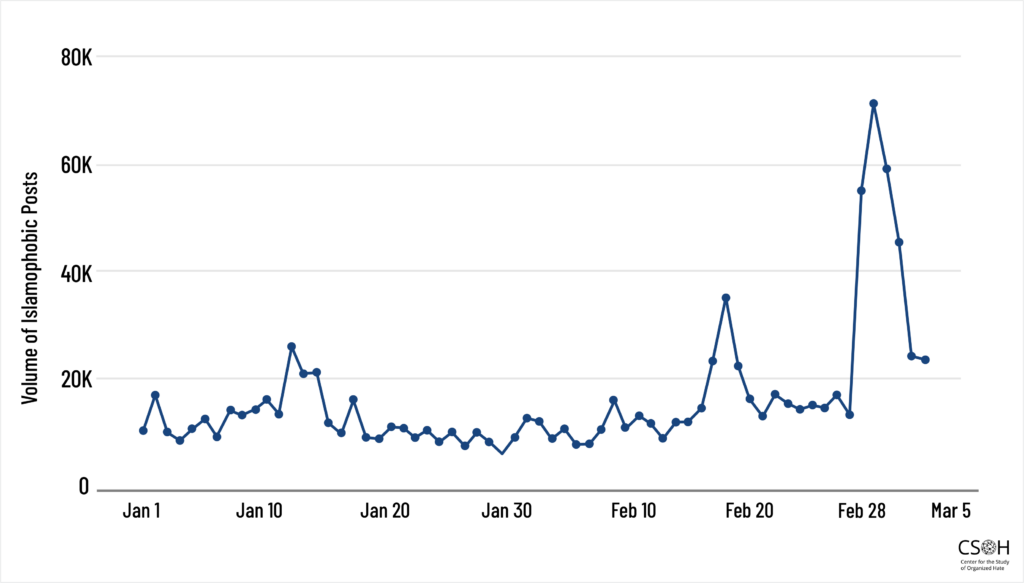

However, the reach of these posts expands significantly once reposts are included. Reposts dramatically amplify the visibility of harmful content, allowing it to spread far beyond the original accounts that generated it.

When reposts are counted, the total mention volume of Islamophobic content rises to 279,417, representing an 11-fold amplification of the harmful original posts.

Figure 2: Volume of Islamophobic Posts on X (Including Reposts), January 1 – March 5, 2026

This amplification is illustrative of how relatively lower volumes of explicitly harmful content can reach extremely large audiences through network effects and platforms’ engagement-driven algorithms. While the volume of Islamophobic content has shown some decline from its initial peak, the underlying conditions that fuelled this surge remain firmly in place.

What are the Patterns of Harmful Content

A qualitative review of the dataset reveals several recurring patterns of harmful discourse. These are not exhaustive categorizations of the full dataset but representative samples that illustrate the nature and severity of anti-Muslim content circulating on X and other social media platforms.

One of the most deeply disturbing patterns running through the posts we reviewed is the use of dehumanizing language, referring to Muslims as “rats,” “pests,” “vermin,” and “parasites.” Such language has historically preceded and enabled the most extreme forms of violence against targeted communities.

Examples of posts referring to Muslims as “rats“

The prevalence of dehumanising language targeting Muslims should be recognized as a significant indicator of escalation risk.

Examples of posts referring to Muslims as “vermin”

Closely related to dehumanisation is the framing of Muslim communities as an “infestation.” Posts using this narrative portray Muslims as a spreading contagion threatening American cities and institutions.

This framing mirrors historical propaganda used against numerous minority communities, in which the targeted group is depicted as a disease or infestation that must be eradicated.

Examples of posts referring to Muslims as an “infestation”

Beyond dehumanisation, we found posts that cross the line from hatred into explicit incitement to violence, including direct calls to exterminate Muslims. Some posts frame the elimination of Muslims as an act of self-defense or civilizational survival, lending a veneer of patriotic duty to the genocidal rhetoric. In the current climate, this content functions as a call to action directed at a community that is already experiencing rising rates of bias, harassment, discrimination, and hate-fuelled violence.

Examples of violent and eliminationist posts

Some of the most extreme posts advocate placing Muslim Americans in internment camps. Others call for the creation of a “Muslim Exclusion Act,” proposing that Muslims be barred entirely from entering the US.

Examples of internment camps posts

A large volume of posts demand the removal of all Muslims from the US. The rhetoric ranges from blanket calls to “deport all Muslims” to specific calls for stripping citizenship from Muslim Americans through mass denaturalization. This category of content is significant not only for its volume but for the way it blurs the line between extremist fantasy and policy advocacy. Many of these posts are framed as actionable demands directed at elected officials.

Examples of mass deportation posts

The CSOH also found posts advocating the destruction of mosques, treating Muslim houses of worship as enemy infrastructure. These posts frame mosques as “mini military bases” and “terrorist centres.”

Mosques in the US have long been targets of arson, vandalism, threats, and shootings. The circulation of content that frames them as legitimate targets increases the risk of violence against Muslim communities and religious institutions.

Examples of posts calling for the destruction of mosques

Failure to Enforce Platform Rules

As part of this analysis, we reported 30 posts featured as examples in this brief to X using the platform’s own reporting categories, including “Violent Speech” and “Hate, Abuse or Harassment.”

These posts included language describing Muslims as “rats” and “vermin,” calls for extermination, demands for internment camps, and calls to destroy mosques. Of the 30 posts reported, 11 were removed. The remaining 19 remain live on the platform as of March 9.

This enforcement gap underscores a critical disconnect between platform policies and their application, particularly when it comes to combating dehumanization and incitement targeting Muslims. The failure to act proactively and to leave up violating content even after it has been reported suggests that existing enforcement mechanisms are either inadequate or inconsistently applied.

Recommendations

The findings in this brief illustrate an environment of anti-Muslim hate and incitement that, while already volatile, has reached a critical tipping point due to the convergence of several factors. These developments underscore the need for urgent action across multiple fronts.

Platform Accountability: Social media companies must strengthen enforcement against harmful content that dehumanizes or incites violence against Muslims. Much of the content documented in this brief appears to violate existing platform policies but remains widely accessible and amplified. Platforms must ensure that enforcement mechanisms respond quickly and consistently during periods of geopolitical crisis, when harmful online content tends to surge.

Establish a Trusted Flagger Network: Platforms should establish Trusted Flagger status for Muslim civil rights organizations with a dedicated reporting channel for flagging mass incitement and threats, bypassing slow standard reporting queues that allow harmful content to spread unchecked during crisis periods.

Political Responsibility: Public officials must exercise extreme caution in how they frame geopolitical conflicts. Language that conflates a military confrontation with a religious or civilizational struggle, or draws on Christian nationalist narratives, risks inflaming domestic hostility toward minority communities. Political leaders have a responsibility to ensure that their rhetoric does not endanger Americans by framing global conflicts in ways that stigmatize entire religious communities.

Community Protection: Civil society organizations, law enforcement agencies, and community leaders should increase monitoring of threats against Muslim communities and institutions. With the heightened risk of targeted violence, there is an urgent need for increased protection of mosques, Islamic centres, and Muslim community organizations across the country.

Stakeholder Briefings and Information Sharing: Relevant stakeholders, including elected officials, law enforcement agencies, and social media companies, should engage with researchers studying Islamophobia to better understand emerging trends in online hate and incitement. Briefings on findings such as those presented in this data brief can help facilitate accurate and timely information sharing. Such engagement can support more informed responses to online narratives and incidents that have the potential to translate into violence targeting Muslims, individuals perceived to be Muslim, and their institutions.

(This data brief represents an initial analysis of an ongoing crisis. CSOH will continue to monitor social media platforms for anti-Muslim incitement, and subsequent briefs will follow.)

Related:

India: Left at the forefront, opposition & people protests US-Israel attacks on Iran

Wars Fought in The Name of Women’s Rights

Hegemony by might: Gaza, Iran and the failures of nuclear power politics

Iran war: from the Middle East to America, history shows you cannot assassinate your way to peace