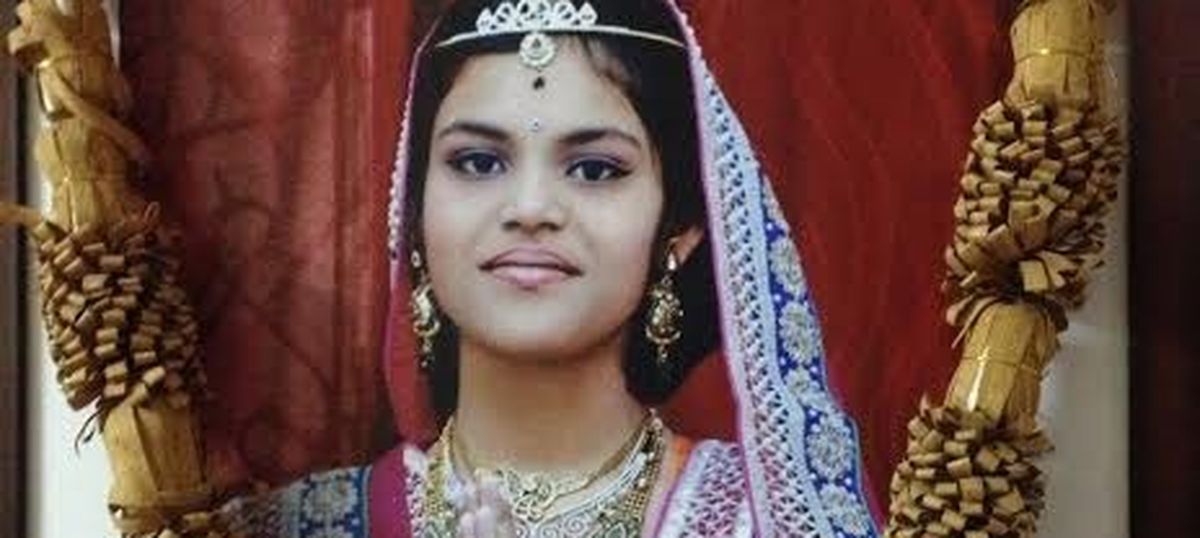

The death of a 13-year-old Jain girl who fasted for 68 days raises questions about how community traditions can impinge on the well-being of minors.'

A mother takes her seven-year-old daughter for circumcision, allowing a part of the child’s clitoris to be cut with a blade in the name of religion. A family allows their 13-year-old daughter to go on a 68-day fast – a tapasya that eventually leads to her death – also in the name of religion.

As the co-founder of Sahiyo, an organisation working to end Female Genital Cutting in my Dawoodi Bohra community, I cannot help but notice the parallels between the two cases.

On October 4, two days after she completed an allegedly voluntary 68-day religious fast, 13-year-old Aradhana Samdhariya died of a cardiac arrest on the way to a Hyderabad hospital. The family labelled her death as “natural” and hundreds of Jains attended her funeral, celebrating the girl as a young saint. Once this news hit the headlines, it led to widespread national outrage, and Samdhariya’s parents were booked for culpable homicide not amounting to murder.

This was clearly an extreme case, one in which a minor girl paid a fatal price for religious indoctrination. But away from the media glare, perhaps in less severe ways, thousands of children in India continue to suffer the consequences of their parents’ religious faith.

The most glaring example, for me, is the secretive practice of female circumcision, or khatna, in the Bohra Muslim community.

Cutting the body, for religion

The Bohras are a small Shia sect, predominantly from Gujarat, who enjoy the reputation of being educated, wealthy and fairly progressive. But for centuries, little Bohra girls have been made to undergo khatna – the ritual cutting of the clitoral prepuce – for reasons that are not even uniform across the community. Depending on which family you speak to, girls are cut either because “it curbs her sexual urges”, or “it prevents urinary infections”, because it is hygienic, or simply because “it is a religious obligation”.

It is well known that the practice of khatna predates Islam and finds no mention in the Quran. So far, no other Muslim sect in India has been known to follow this ritual. But Bohras have clung on to this tradition, carrying it with them even when they migrate to other countries. In many cities and towns, the dingy homes of traditional midwives and cutters have given way to sanitised clinics and Bohra-run hospitals, but the cutting continues.

Snipping the clitoris, unlike male circumcision, has no known medical benefits. On the contrary, it could lead to bleeding, infections, reduced sexual sensitivity or long-term psychological scarring. Khatna also falls within the World Health Organisation’s definition of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting, a practice illegal in several countries because it is a human rights violation. In fact, in November 2015, three Bohras in Australia were convicted under the nation’s anti-FGM law for carrying out the circumcision of two minor girls. Despite this, the Bohra religious leader – whose headquarters are in Mumbai – publicly endorsed the cutting of minor girls as recently as June.

For the past year, there has been an increasingly vocal opposition to khatna from within the community, but Bohra girls are still taken by their mothers, grandmothers or aunts to get cut, most often at the age of seven. And there is no law against the practice in India so far.

Not old enough

How does this practice compare to the death of young Aradhana Samdhariya in Hyderabad?

According to news reports, Samdhariya’s parents have claimed that they never forced their daughter to go on the 68-day fast. They claim she had always been “religiously inclined”, had done a 34-day fast before and was adamant about doing a longer tapasya this year. Samdhariya’s grandfather has stated that the family had first opposed her decision, but eventually had to choose between allowing her to fast or allowing her to take diksha (more on that later) at an older age. Some reports also claim the girl took up the fast on the advice of a spiritual guru, to help her family business grow, although her relatives have refuted this.

But none of these attempted rationalisations should matter at all. This issue is about the religious fervour of families and cultures impinging on the well-being of those too young to give informed consent or understand the long-term implications of certain rituals and practices.

At 13, Samdhariya may have been older than the little Bohra girls taken for khatna, but she was still unarguably a minor, both legally and culturally.

Legally, her parents were clearly responsible for ensuring her health and safety, and 68 days of surviving on just warm water is neither healthy nor safe. (One would expect Jains to know this well, given that many elderly Jains undertake the controversial santhara fast for the sole purpose of waiting for death.)

And culturally, in a country where even legally-adult children are often not allowed to choose their own careers or spouses, an adolescent would certainly not be considered old enough to choose such a risky fast.

Religious relativism

But India is a country where religious and cultural relativism often trumps all logic and rationality. Legally, a 16-year-old may be considered too young to have consensual sex, but if she’s been forced into an illegal child marriage, even marital rape would be considered permissible.

Culturally, a seven-year-old would be deemed too young to be told about sex, but if she’s a Bohra, her parents would willingly cut her clitoris – her centre for sexual pleasure – without questioning the logic behind it.

We celebrate the innocence of childhood and uphold the idea that children shouldn’t be made to bear adult burdens, but many Jains are happy to allow children – some as young as 11 or eight – to give up all worldly life for complete asceticism in a controversial practice known as bal diksha. This is a practice that requires children to give up school education, family life and material pleasures and take up the austere life of monks. Supporters of the bal diksha claim children are never forced into it – they are allowed to become ascetics only if they want to.

Should a child be allowed to take such a decision, though? Jains themselves are divided on this issue, and the legality of bal diksha is still being disputed in the Bombay High Court. But disappointingly, in 2009, the Delhi Women and Child Development Department actually recognised bal diksha as a religious right.

Booking Samdhariya’s parents for culpable homicide is definitely a step in the right direction. But should it really take the death of a 13-year-old for us to question the dangers of practices like this?

This article was first published on Scroll.in