Nawadih village, Koderma district (Jharkhand): Jumman Miyan was having a relaxed morning. The last few days had been very busy for him–his son’s wedding celebrations were on, which close to 400 relatives, the entire Muslim community in the village as well as a handful of Hindu villagers had attended. The festivities had ended the night before with a lavish feast.

The morning after his son’s wedding, Jumman Miyan of Nawadih village in Jharkhand’s Koderma district was attacked by a mob. Messages had gone viral on WhatsApp containing photos of animal remains found in the village, alleging that Miyan had served beef at the wedding feast. WhatsApp is often employed as a carrier of hate messages in Jharkhand. It is also helping some victims seek justice.

That April 2018 day, the morning after the feast, as he was bidding goodbyes and handing out wedding favours to relatives, something caught his eye.

In the clear vision his house offered to the “jungle”, as the villagers call the barren expanse of surrounding land, he saw that around 800 metres away, a crowd was gathering near a pink house. “Something felt off, so I went there with my son, Nayyum, to find out what had happened,” Miyan told FactChecker on a recent April day, in his deep baritone.

Some heads turned towards him. Some men were holding up a black polythene bag with animal remains–he could see the hoof of a young bovine.

“Jolha Miyan, you had a party last night where you served beef and then you ask what happened,” the crowd said. ‘Jolha’ is a pejorative used to refer to Muslims.

Some of them started pushing him about but his son intervened and whisked him out.

Back home, Miyan tried to understand exactly what had happened, but within minutes, he saw a mob approaching. “They were in the thousands and I didn’t know what to do,” Miyan said. Breaking into the house, the mob caught Miyan by his beard and threw him to the ground. “Then, they started beating me with what looked like baseball bats. Someone hit my head and I fell unconscious.”

The mob assaulted his family and ransacked their house. The violence spread–nearby vehicles were damaged, the local mosque was ransacked and a maulvi (Islamic religious scholar) was also assaulted, locals said.

Miyan later pieced together what had happened. Some Hindu villagers had found two bags of animal remains near Hindu homes. Within minutes, photos of these remains were on WhatsApp with the message: Miyan served beef at his son’s wedding feast.

That message was forwarded to different people in various neighbouring villages, said the village’s 29-year-old mukhiya (head-woman), Kumud Devi. “It was all because of WhatsApp. Because of it, the mob just swelled,” she said, adding that she had rushed to Miyan’s Muslim locality on hearing of the violence.

“They were all outsiders,” Devi said. “They all came here, angry.”

Kumud Devi, 29, the village head of Nawadih in Jharkhand’s Koderma district, is clear about what led to the attack on Jumman Miyan and the local mosque following a wedding feast in April 2018. “It was all because of WhatsApp. Because of it, the mob just swelled,” she says, talking of the misleading photos alleging cow slaughter that had gone viral.

This was not an isolated incident.

Jharkhand, with 68% Hindu population, 14.5% Muslim and 4.3% Christian (12.8% profess ‘other religions’ including tribal religions), is India’s second-deadliest state in terms of religious hate crimes. Since 2009, Jharkhand has recorded 14 hate crimes motivated by religion and nine deaths in our Hate Crime Watch database, just behind Uttar Pradesh with 23 deaths. All of them have been reported after the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won national and state elections in 2014. The BJP has returned to power at the national level in recent elections whose results were declared on May 23, 2019. In Jharkhand, it won 12 of 14 parliamentary seats along with ally All Jharkhand Students’ Union.

Nationwide, over a decade to 2019, 93% of 287 hate crimes motivated by religious bias–which claimed 98 lives–were reported after 2014, according to the database.

Our investigation of seven hate crimes across the state found that WhatsApp, the popular but increasingly controversial messaging phone application, is often being employed as a carrier of hate messages.

Messages, often false and misleading, go viral on WhatsApp, polarising communities and instigating violence. But WhatsApp is also being deployed to spread visuals of hate crimes, sometimes live, often to drive fear into the minds of communities and to valourise the accused.

WhatsApp and India: A turbulent affair

The Indian experience of WhatsApp, the popular personal messaging application with an estimated 200 million users in India, its biggest market globally, has been wracked with controversies.

In 2017, police investigations showed that misleading WhatsApp messages about ‘child kidnappers’ had led to serial lynchings, leaving seven people dead in two episodes. Apart from these, 24 people across the country were killed over similar rumours, which had gained traction primarily through WhatsApp forwards. Many of these were in Jharkhand.

A WhatsApp India spokesperson said the company had taken steps to curb such forwarding of messages on its application, such as limiting the number of times a person can forward a message, while admitting that more needs to be done. “This step has reduced the amount of forwarded messages in India by over 25%. We continue to explore new solutions to address the spread of viral misinformation.”

The spokesperson said the company did not have any insights into why Jharkhand was repeatedly seeing such instances of misuse of WhatsApp.

Over two weeks of travels in Jharkhand, FactChecker found that in at least three of the seven hate crimes that we tracked, videos and images of the crime had reached WhatsApp almost immediately. In fact, the victims’ families had found out about the lynchings through WhatsApp videos and images, even while the attacks were afoot.

This is what happened on August 19, 2017, in Barkol village of Garhwa district in northwest Jharkhand.

‘How could I believe WhatsApp?’

Anita Minj, a Christian tribal from the Oraon tribe, had been worried. Her husband, Ramesh, had not come home the previous night. When she had tried calling him, an unknown voice had answered the phone, saying Ramesh had been “sent back”. The phone had then been switched off.

So, at 9 a.m. the next morning, as she started getting ready to go to Barkol village, where Ramesh was supposed to have gone, a neighbour came up to her with his phone. “He asked me, ‘Did you hear?’ I said, ‘Hear what?’ So then, he started showing me videos on WhatsApp of Ramesh being lynched by a mob,” Minj told FactChecker.

The caption accompanying the videos said a man had been caught consuming beef and assaulted.

The neighbour told Minj the visuals had gone viral in the area. She watched the videos again and again until she could convince herself they could be true, she said. She herself did not have WhatsApp.

Minj said she rushed to Barkol, where the family’s farm is located, but local Hindu villagers initially stalled her. “They refused to let adivasis [indigenous tribals] from our Tengari village to go to their village. But I persisted and started asking questions about the lynching and whether it was true,” she said. On going to the nearby police picket, she found Ramesh, who had been arrested for cow slaughter.

Piecing the story together, Minj said, she found out that some men of the Oraon community, including Ramesh, had consumed beef, as was their custom.

But Jharkhand had banned cow slaughter in 2005 under the Jharkhand Bovine Animal Prohibition of Slaughter Act, making beef consumption a crime. Cow slaughter is a cognisable crime (implying that the police can make an arrest without prior permission from a judge) and a bailable offence, punishable with a fine of up to Rs 10,000 or up to 10 years of imprisonment.

A mob of Hindu locals from nearby villages had assaulted the Oraon men while they were on their way back to their village. The assault had left Ramesh badly injured–reports show his leg had such a big gash that his bone had shown through. Three days later, Ramesh had died.

Earlier in that year, something similar had happened to Mariyam Khatoon in Jharkhand’s Ramgarh district, 300 kilometres away from Garhwa.

WhatsApp as evidence

The day was a blur for Mariyam Khatoon: first, she had heard that her husband had been lynched on a busy Ramgarh highway for carrying sacks of beef; later, that he had died. Then, she had spent three hours waiting to receive his body.

But there was work to do. For instance, a police complaint had to be filed so that the police could act against those who had lynched her husband Alimuddin to death early that morning of June 29, 2017.

There was a problem, though. “We didn’t know too many people who had seen the crime happening. Most bystanders would refuse to testify, we figured,” said Khatoon, explaining her dilemma, while trying to push the police to investigate the lynching.

Earlier in the day, neighbours and local boys from her basti in Ramgarh city’s Manuwa locality had come to her doorstep, holding mobile phones. “They kept looking at me, almost like they were wondering if they should show me what they were seeing. When I saw them doing this, I asked what was wrong,” Khatoon said.

On the July 2017 morning when her husband Alimuddin was killed, Mariyam Khatoon was at home when neighbours suddenly crowded her house, with phones in their hands. They had all received videos on WhatsApp showing her husband Alimuddin being attacked by a mob.

The neighbours had received videos on WhatsApp–of Alimuddin, her husband, being lynched in full public view.

Watching the visuals of the fatal assault playing out was traumatic, Khatoon said, but they also became her biggest weapon–they would help the police identify the assailants.

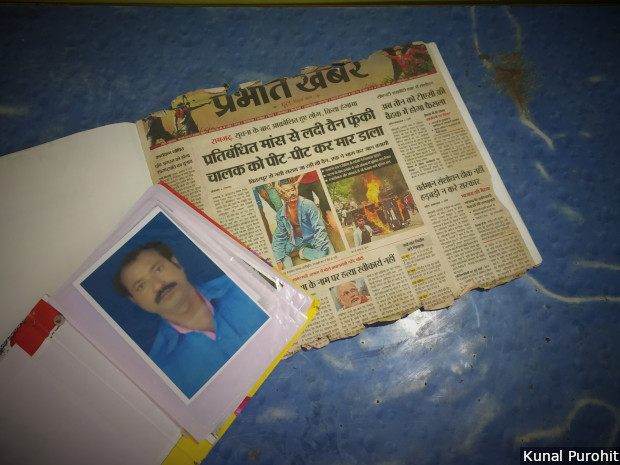

Watching visuals of the fatal assault on her husband Alimuddin on neighbours’ WhatsApp was traumatic, Mariyam Khatoon says, but they also became her biggest weapon: they enabled Khatoon and her sons to create a photo album of zoomed, still images of at least nine assailants, with additional photos from their Facebook accounts, to be used as evidence to get justice.

“We went back to the video, and frame-by-frame, started trying to identify all those who were involved in the lynching,” Khatoon told FactChecker, sitting in her living room and staring out the window.

Khatoon and her eldest son, 22-year-old Shahzad, with help from friends and family, froze each frame and painstakingly identified each assailant. “Once we found a face, we would ask around if anyone knew that person. After someone identified the person, we would go to their Facebook accounts and confirm their identities,” Shahbaz, Khatoon’s 15-year-old son, said.

This resulted in a photo album, one that now lies at a hand’s reach in the bedroom, ready to be displayed to any visitor. The album has zoomed images of at least nine assailants, with additional photos from their Facebook accounts.

“We then went to the police with this list and asked them to register a First Information Report [FIR],” Khatoon said.

The case came at an embarrassing juncture for the Jharkhand government–the lynching happened just as Prime Minister Narendra Modi in New Delhi issued a warning to gau rakshaks (cow-protection vigilantes) against violence in the name of cow worship.

Left red-faced by the evidence Khatoon presented, the state government issued strict orders to ensure action against the accused, sources in Jharkhand Police told FactChecker.

But even as the videos became a crucial tool for Alimuddin’s family, one of those convicted for his murder has alleged that he was made an accused only because he was present at the scene of the crime.

Former BJP district media cell in-charge Nityanand Mahato, speaking to FactChecker, said he had been unfairly arrested: “I was passing by because my office is opposite the spot where the lynching happened. Someone shot a video of me being present there and on the basis of those videos, Alimuddin’s family named me as an accused.”

Having secured bail from the Ranchi High Court, Mahato is currently out and insisted to FactChecker that he was not even an eyewitness. “When I reached the spot, the police had taken Alimuddin away already. The crime had already been committed.”

The 50-year-old former BJP leader, who contested the 2009 state assembly elections from Ramgarh as an independent candidate, said he was being accused of murder “solely on the basis of some photographs”. “I spent 15 seconds at the spot and the visuals of those 15 seconds are going to haunt me for life,” said Mahato, now a real-estate dealer, sitting in his Ramgarh home.

Ramgarh police dismiss Mahato’s assertions. “It is true that we relied on the initial videos and photos that went viral on WhatsApp. But we followed those leads with fool-proof investigations and only then framed charges against the accused persons,” said Nidhi Dwivedi, superintendent of police for Ramgarh district.

Dwivedi said social media tools such as WhatsApp have helped investigations of such violence. “What accused persons don’t realise, when they shoot videos of such acts of violence, is that these clips turn out to be very valuable tools for police investigations,” she added.

This is the second in a five-part series. You can read the first part here.

(Purohit is an independent journalist and an alumnus of the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, writing on development, gender, right-wing politics and the intersections between them.)

Courtesy: https://factchecker.in/