Photo Credit: Caravan Magazine

The whys and wherefores behind the recent media gag by the state in Kashmir

Note from the author: The ban is off from July 21 but I can safely say that the article remains relevant, looking at the larger picture.

“By the skillful and sustained use of propaganda, one can make a people see even heaven as hell or an extremely wretched life as paradise”

– Adolf Hitler

Hitler’s Nazi regime ruled the German public with two main weapons – propaganda and censorship – ensuring that they had the public in their grip as they bombarded them on a daily basis with the glorification of Hitler, convincing them about the better prospects of their lives but ensured complete and blanket silence over the gory stories of holocaust and concentration camps. The stories eventually did come out – in the form of narratives, fiction, diaries and reports.

There is no way one can keep a lid on facts forever. Narratives tucked away and hidden, will resurrect to be told, re-told and heard.

If that be so, then what is it that the Jammu and Kashmir government was trying to achieve by banning newspapers — and doing so in a brazen and rash manner of clamping down on newspaper offices by conducting raids and arresting staffers in the dead of the night–amidst one of the worst and violent crisis that Kashmir is presently facing? Was it trying to stop them newspapers from reporting and journalists from commenting? Was it trying to block all channels of information so that people remained ignorant? Few days down after the clampdown, so far, the PDP led coalition government comes across as unsure on the issue.

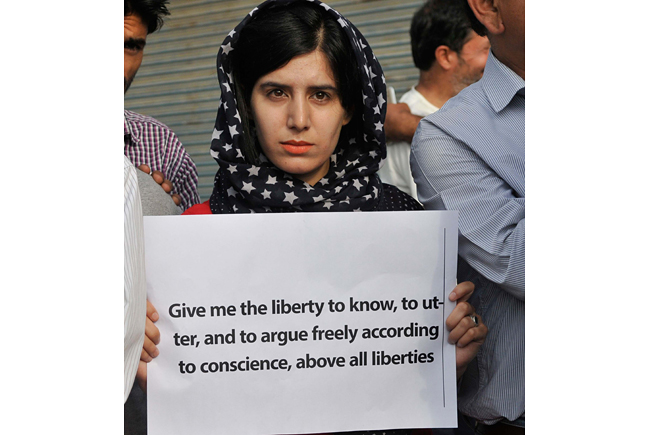

After newspaper printing presses and offices were visited on July 15 by unwanted midnight guests in uniform who packed the visit with intimidation, abuse, handcuffs even as they walked off with newspapers, printing material and personnel (technical staffers) of at least two of the newspapers (including my own), media persons in Srinagar staged a protest march. Journalists also met the Divisional Commissioner who, while being evasive on the raid and ban, said that he was in no position to provide the media with any curfew relaxation passes to allow them to discharge their duties, nor could he assure journalists any protection.

Two days later, PDP minister Nayeem Akhtar went to the extent of telling a television news channel that the move to stop publication of newspapers was necessitated sensing ‘trouble’. A day after he took charge of the midnight-declared state of Emergency, chief minister Mehbooba Mufti’s political adviser, Amitabh Mattoo maintained that there was no ban and that the chief minister had no idea about it. The government transferred a superintendent of police, blaming him for recklessly cracking down on the press.

Which of these versions is true? The newspapers hit the stands again after six days on Thursday, July 21, following an assurance from chief minister Mehbooba Mufti. This should, however not be treated as the end of the story.

Important questions need to be asked. A week long ban on newspapers, a belated response of the government necessitated probably by the unusual solidarity from sections of Indian journalists and intellectuals, was not without design. It was nothing but ill advised. Who was the brainchild behind the move which may eventually become a footnote, but is no less significant. The move and the motive need elaboration. First things first, why was this done? Who instructed the now out of favour Superintendant of Police?

The logic behind any bans stems from the necessity to hide. All Internet connections and mobile phones have already been partially snapped since July 9. In the worst affected areas, the landline phones have also been disconnected. Newspapers have not been allowed to be circulated freely due to the prevalent curfew restrictions. All this has made the information from the public to media and vice versa filtered and restricted, as it is.

Important questions need to be asked. A week long ban on newspapers, a belated response of the government necessitated probably by the unusual solidarity from sections of Indian journalists and intellectuals, was not without design. It was nothing but ill advised. Who was the brainchild behind the move which may eventually become a footnote, but is no less significant.

The state government’s worry is not that if these filtered bits and pieces of information find their way to print they would provoke more violence than there already exists. In this day and age of internet and gizmos, that job was being managed partially despite the ban on newspapers who continued to maintain and update their websites and circulate whatever they could through digital applications, even though this meant that news was reaching far fewer numbers of people.

The government’s anxiety is with the printed word becoming an authentic piece of documentation with a longer shelf life. The national television channels were switched on 24X7 and national print media was not subjected to any kind of similar ban. The ban, and the need for the ban from the state and government’s point of view, highlights the vast chasm between the perspectives reflected in the regional press and the national press, with respect to Kashmir.

While an ultra-nationalist narrative inspires the former, the latter give ample space to voices of the common Kashmiri and Jammu resident, suffering due a perpetual state of conflict. It is the local newspapers that fill in the gaps left by either the silence or jingoism of the ‘national’ press. In recent days, despite the hurdles of obtaining authentic information amidst curfew bound streets and crackdown on communication systems, it is the local newspapers that have managed to source and publish the narratives that tell the story of the atrocities on the people; chilling stories about how people got killed and about the injured recuperating in the hospitals, about the pellet guns playing havoc with people’s lives, impairing them physically for their life time; of the 130 blindings by pellet guns of mostly children and teenagers.

It is these stories that rarely make it to the pages of major ‘national’ mainstream newspapers, which are a major challenge for the State peddling its lies about what is happening in Kashmir.

This is not the first time that attempts have been made to muzzle the press. Earlier, in 2010 and 2013, the newspapers were unable to publish newspapers and circulate or distribute copies, because of excessive curfew restrictions and the denial of curfew passes to media persons that prevented journalists from stepping out. In striking contrast, while the Valley was forced to remain without newspapers, commercial television crews who flew in from Delhi were provided escorts to move across the Valley and offer a point of view that suited the government.

There is a definite pattern behind this –in how both the commercial media and government relations operate. Through this cynical game of muzzling the media, it is the Central Government that seeks to reap the rich harvest from this demonizing of a people’s resistance, dwarfing their victimization and creating the a hysteria around ultra-nationalism which is the new normal in much of ‘national’ media’s reportage on Kashmir.

That the present gag on the local, regional media, could have been inspired by Delhi cannot be ruled out, nor the fact that it was effected through orders to some of its cronies within the police and administration. The state government, ignorant or otherwise, cannot be condoned either for its ineffectiveness, or for acquiescing without any application of mind, especially on the consequences.

It is the local newspapers that fill in the gaps left by either the silence or jingoism of the ‘national’ press. In recent days, despite the hurdles of obtaining authentic information amidst curfew bound streets and crackdown on communication systems, it is the local newspapers that have managed to source and publish the narratives that tell the story of the atrocities on the people.

It is all about chaining and imprisoning a narrative, controlling it, stifling its telling and super-imposing on the real, local story, a manufactured narrative of ultra-nationalism, of ‘paid agents’, of ‘jihadi terror’, of ‘things under control’, of an enemy called Pakistan and of normalcy and happy pictures of tourism.

What bigger proof does one need of India’s moral defeat with regard to the Kashmir conflict than this reality of employing weaponry of lies and propaganda to hide the ugliness of bullets, blinded children, torture and brutality?

The narrative, as it is, has been controlled. In the history of 26 years of insurgency, the media has been tamed and silenced through the use of many devices. In the beginning of the nineties, caught between the gun of the militants and the security forces, intimidations, physical attacks, even murders and curfews, though newspapers continued to be published, writing more insightful and detailed stories almost amounted to committing suicide. Many newspapers even went without editorial content to play safe.

When media gradually began to evolve, freeing itself from the clutches of ‘anti-movement’ and ‘Indian nationalistic’ discourse, the government cracked down with fresh arm twisting methods – squeezing the financial flow of the newspapers by stopping their government advertisements particularly the central government-controlled DAVP advertisements, the main source of revenue for newspapers in Jammu and Kashmir.

In 2010, the advertisements to several Kashmir based newspapers were stopped following a letter from the union home ministry, which gave no explanations for this withdrawal of financial support. The order was dutifully followed. In subsequent years, while advertisements of most newspapers have been restored (arbitrarily or otherwise), Kashmir Times (of which I am the Executive Editor), printed out of both Jammu and Srinagar has been singled out and kept starved of funds.

Shockingly, the interlocutors appointed by the Indian government after the 2010 killings to look into the grievances of the people in one of their recommendations suggested that there was a need to publish national papers out of Srinagar as the local newspapers were “unreliable”!

In 2010, the state government also banned the local cable television channels in Srinagar from screening news based programmes on the pretext that these channels were not duly registered. However, in Jammu, similarly un-registered channels continue to operate without any hindrance.

The media, thus, has been already in chains. In a near permanent curfew-imposed situation, the media is further imprisoned by the lack of information and the crackdown on communication systems. So what then makes even the present gag order unique? And what purpose was it meant to serve?

In a fashion, it is just another link in the sequence; in another, it reflects the growing and increasing penchant of the government for absolute control, exercised deliberately through power of the brute force of khakhi, in brazen violation of law, ethics and democratic principles itself.

Now, like then, when gory stories of boys dragged out of their homes and shot at point-blank range, tales of random arrests, crackdowns and molestations, of children blinded by pellet guns who have gone missing, abound, yet another unbridgeable chasm has opened, defying resolution of the churning that is Kashmir.

Successive governments, both in the state and at the Centre, have looked upon local media as deadly missiles that need to be kept under check and control, not as sources of information that the government itself can rely on for feedback about both the day to day needs of the people as well as their oppression, anger and political aspiration. The existence of a professional regional media, rooted in Jammu and Kashmir marginalizes rumour mongering, because –notwithstanding crtain biases — media houses are guided by certain professional ethics. A free media can provide a vital link between the public and the government, conveying what a people are feeling and doing, vital to a region mired in conflict. It is worthwhile now recalling Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s 2015 arrogant snub of then chief minister Mufti Mohammed Sayeed who was urging for political dialogue with the Kashmiris. “We don’t need any advice from anybody on Kashmir”, Modi had famously said.

It is this mindset that inspires men in power to not just crush a population brutally but also crush the voices speaking for them. Their aim is to make the narrative disappear.

But, as history reveals and as human minds are known to work, and remember, sooner or later the narratives will emerge – emerge to haunt, often with a dash of bitterness and sometimes peppered with rumours. Sometimes dangerously so.

In January 1990, during the infamous days of strict curfew and black-outs in the wake of Jagmohan taking over as Governor, the information flow remained very limited making the reportage of both the flight of Kashmiri Pandits and the slew of massacres starting from Gawkadal that Kashmir witnessed, both rather sketchy and flimsy.

In subsequent years, those stories have been told and re-told at individual and community levels with little possibility of authenticating the narrative: sometimes one does not know where to sift fact from fiction as the stories have emerged with such contradicting and contrasting perspectives that just do not match.

It is this huge chasm, the chasm of the missing truth telling of those dark days that continues to play a role in shaping the communal divide within Kashmir. Now, like then, when gory stories of boys dragged out of their homes and shot at point-blank range, tales of random arrests, crackdowns and molestations, of children blinded by pellet guns who have gone missing, abound, yet another unbridgeable chasm has opened, defying resolution of the churning that is Kashmir.

(The author is Executive Editor, Kashmir Times)