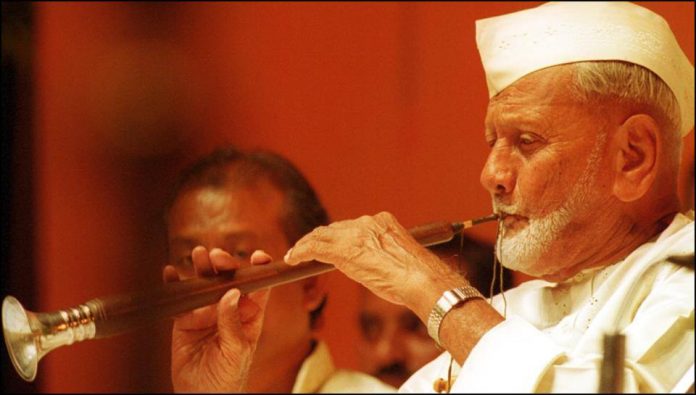

There are moments when I love my job or rather, my business of journalism – even I, a hard-nosed cynical hack of nearly three decades. It is because you love and cherish these moments that you are so grateful you are in this business. How else would I, a hopeless, hopeless philistine, hope to find myself on a rain-drenched terrace in old Varanasi with Ustad Bismillah Khan? As it happens, it was almost exactly the same time last year.

I can fill the rest of this space just describing the beauty of his face, his spirit, his talent, his madness, even his commercialism. To date, he is the only guest who demanded, and was paid – though only a very reasonable tribute – for appearing on Walk the Talk. He said he had a large family to support, even at 91, and could do with whatever money came his way. And when I reminded him, while leaving, that he had to come and perform at my children’s weddings, he said yes immediately. And then quoted the price: five lakh, plus air tickets and stay for seven people. You could touch his innocence with bare hands in the heavy monsoon air.

Khan Saheb let me down on this one though. He will not come and perform at my children’s weddings, whatever the price. But he left me with memories – and lines – that will never go away. What was the difference between Hindu and Muslim, he asked. What, indeed, when he sang to Allah in raga Bhairav (composed for Shiva) and brought to tears the Iraqi maulana who had just told him music was blasphemy, “evil, a trap of the devil”. Khan Saheb said, “I told him, Maulana, I will sing to Allah. All I ask you is to be fair. And when I finished I asked him if it is blasphemy. He was speechless.” And then Khan Saheb told me with that trademark mischievous glint: “But I did not tell him it was in raga Bhairav.”

Why did Khan Saheb not migrate to Pakistan with partition? “Arre, will I ever leave my Benares?” he asked. “I went to Pakistan for a few hours,” he said, “just to be able to say I’ve been there. I knew I would never last there.” And what is so special about Benares, his glorified slum of a haveli in a grandly named Bharat Ratna Ustad Bismillah Khan Street that had more potholes than footholds and more heaps of chicken entrails from nearby meat shops than garbage heaps from homes? “My temples are here,” he said, “Balaji and Mangala Gauri.” Without them, he asked, how would he make any music? As a Muslim he could not go inside the temples. But so what? “I would just go behind the temples and touch the wall from outside. You bring gangajal, you can go inside to offer it, but I can just as well touch the stone from outside. It’s the same. I just have to put my hand to them.”

How is that devotion in a week when our parliament was rocked by issues like the forcible, and criminal, chopping of a Sikh boy’s hair in Jaipur and the controversy over state-mandated singing of Vande Mataram in schools to launch the 150th anniversary of 1857? Or when we were all so outraged by the paranoia that caused the Mumbai bound KLM-Northwest flight to return to Amsterdam, the racial profiling of Muslims, particularly Asian-Arab Muslims and so on?

Khan Saheb’s was a talent worthy of a Bharat Ratna and immortality. But he also personified, so strikingly, the fact of how the Muslims of India defy the stereotypes building up in today’s rapidly dividing world. They may be poorer than the majority, or even other, smaller minorities, they may still live in ghettos of sorts, but they are a part of the mainstream, nationally as well as regionally and ethnically, more than Muslim populations are in most parts of the world. A Tamil Muslim, for example, is as much an ethnic Tamil as a Hindu or a Christian and certainly has more in common with his ethnic cousins than with fellow Muslims in Bihar or Uttar Pradesh. India’s Muslims work in mainstream businesses where their interests are meshed inextricably with the rest, particularly the majority Hindus, even if they happen to spar occasionally.

That is why, unlike Bush’s America or the western world in general, India cannot even think of the diabolical idea of “Islamic” fascism or terrorism. No country can survive if it starts looking at nearly 15 per cent of its population as a fifth column. That is why India’s view of the war against terror has to be entirely different from the western world’s, more nuanced, more realistic and, most importantly, entirely indigenous.

It is a difficult argument to make in times when it is so tempting to tell America and Europe that see, the people who are terrorising you are the same as the people who have been terrorising us. So far you never believed us. Now with every other terror suspect being traced back to Pakistan and, more precisely, Jaish or Lashkar, accept and acknowledge that we have been in the forefront of the global war against terror for a decade before it hit you. The danger in that approach is, the Americans and the Europeans can choose that approach – though it is not working for them as well – because for them these Muslims are outsiders, different, and therefore candidates for racial profiling. You can racially profile a million people in a universe of 27 crore. Can you profile 14 crore in a universe of a hundred crore? Particularly when most of them, in their own big and small ways, are as integrated in the mainstream, as zealously proud and possessive of their multiple (ethnic, linguistic and professional) identities as of their faith?

That is why the key to fighting, okay, this wave of terror emanating from Muslim anger is to absolutely avoid the “global war on terror” trap.

The terrorists know it. That is why attacks in India, even by angry Indian Muslims, are not directed against some evil global power or its symbols. Nor are they meant to support some pan-Islamic cause, Palestine, or even, for that matter, Kashmir. Their objective, always, is to strike at our secular nationalism. Every single attack has had the same purpose, starting with the first round of Bombay bombings in 1993.

Sharad Pawar made a bold confession to me earlier this month that he parachuted from Delhi into a riot-torn Bombay then figured immediately that the terrorist plot was to kill a large number of people in Hindu localities to trigger large-scale mob attacks on Muslim areas where automatic weapons and grenades had been stored with their agents. Once the mobs were stopped with these automatic weapons it would lead to a carnage that would be uncontrollable. It is for that reason that, he says, he lied on Doordarshan that there had been 12 blasts (where there had been 11) and added the name of a Muslim locality as the 12th. Today we can all rue the fact that judgement in the case of those blasts is still awaited, 13 years later (this article was written in 2006). But we should also cherish the fact that in eschewing any rioting and actually returning to work the very next morning, Bombay had defeated the larger design of the terrorists.

Every attack since then, the temples at Ayodhya, Akshardham and Varanasi, Raghunath temple in Jammu, even the bombs at Delhi’s Jama Masjid, had the same purpose: widening that divide. But it is tougher in India where any notion of ‘Them versus Us’ is an impossibility given how closely communities live, work and do business together. It is one thing to say that we have learnt to live with diversity for a thousand years. It is equally important that we internalise the idea of diversity, equality and fairness that is in our Constitution and in the process of nation building make the very idea of a global war against ‘Islamic fascism’ totally alien and ridiculous for India.

There is a war on for us and there is no getting away from the fact that some of those on the wrong side today are fellow, angry Indians, and we have to deal with them firmly and effectively. But we will need to evolve an idiom and a strategy entirely our own, in tune with a society which loves equally Ustad Bismillah Khan and Pandit Ravi Shankar, who both sing and pray to Allah and Shiva, Krishna in ragas composed for either. Today India enjoys great respect in the world because of its unfolding economic miracle. If India can get this nuance right, it could be the toast of the world tomorrow for an even greater socio-political miracle, a secular but deeply religious nation that defeated terrorism while taking its 14 crore Muslims along.

Courtesy: The Indian Express

Archived from Communalism Combat, August-September 2007, Anniversary Issue (14th), Year 14 No.125, India at 60 Free Spaces, Music