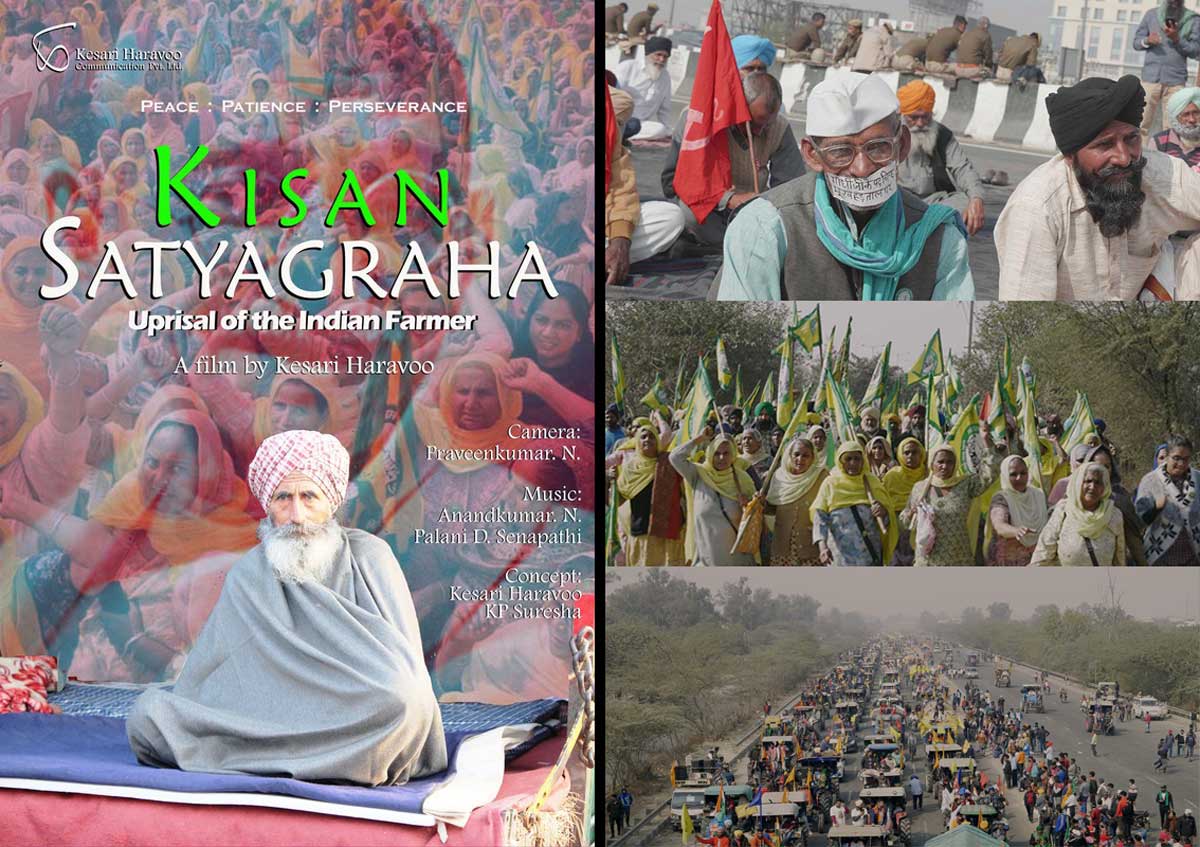

Since February 2024, the farmers of India have been protesting on the borders of Punjab and Haryana to demand a law on Minimum Support Price (MSP), a promise that was made to them by the current ruling Bharatiya Janata Party government during the Farmers Protest of 20-21. It was based on this promise that the farmers had then paused their year-long protest. As was expected, the said promise was not delivered upon. And now, with the same vigour, the farmers have launched their protest. To refresh the memories of the first protest, we took to watching “Kisan Satyagraha – Tremors of Change?” a documentary on the 2020-21 farmers’ protests in Delhi. The 90-minute documentary had been directed by critically acclaimed Kannada director Kesari Haravoo.

Haravoo began with the shooting of this film on December 4 last year, when the Delhi Chalo sit-in had just started. In the documentary, Haravoo has not only captured glimpses of the protest sites but has attempted to show the reason behind the farmers’ dissatisfaction with now repealed three new farm laws that the Modi-government had wanted to implement. Through this movie, it became clear that the farmers protesting against this law had a deep understanding of the motive of the ruling government for introducing the three “black” farm laws and the consequences that these laws would follow. This was in stark contrast to the narrative being built by the BJP ministers and those supporting the ruling government, which had accused “foreign involvement” and “political motivation” behind the protest.

The film covers the whole farmers’ protest, from the violent way that farmers were attacked with water cannons and tear gas shells on November 26, 2020 by the state police to prevent them from entering Delhi to the Lakhimpur Kheri incident. The film concludes with the visual of Ashish Mishra, the son of Union Minister of State for Home Affairs Ajay Mishra, allegedly mowing down a group of farmers in Lakhimpur Kheri, Uttar Pradesh, on October 3, 2021. In between these two major events, which are about a year apart, the film shows the undying strength and the strong resilience that the Indian farmers showed in the face of numerous obstacles and needless discouraging events. It also covered the January 26, 2021 protest of farmers which had turned violent.

It is essential to note that in March 2024 itself, “Kisan Satyagraha” had been barred from screening at the 15th edition of Bangalore International Film Festival (BIFFes) following “instructions” from the Union information and broadcasting ministry (MEITY). According to government officials, the screening of the documentary to be showcase as it was on a “sensitive subject.”

The three farm bills:

The All India Kisan Sangharsh Coordination Committee (AIKSCC) head, Dr. Darshan Pal, states in the film: “Farmers in this country were already fighting on two issues, one is the issue of minimum support price and the other is the issue of indebtedness.”

The movie shows the extensive efforts that were put in by the farmers to understand these laws themselves and make other farmers aware about them too. Dr. Darshan Pal had further provided in the film that as soon as these ordinances were implemented, they had requested their economists’ friends to review them. The film then showed how farmer leaders spoke with peasants at the village level and had the ordinances translated into Punjabi, helping them realize that the laws would spell disaster for small, disenfranchised, and landless farmers. It became clear then that the farmers’ protest had not just taken place spontaneously, rather much thought and understanding had been put behind these protests/

The farmers were adamant regarding the repeal of the three farm laws that were enacted in September 2020. These three laws were: The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020, The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020 and The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act, 2020.

In the film, a protesting farmer from Agra had explained the issued that the farmers had with each of these three laws. The gist of the issues highlighted was that these three laws were giving backdoor entry to corporates to take over the market. Through the Promotion and Facilitation Act, Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs) would become obsolete.

In India, farmers used to directly deal with traders to sell their products. However, this led to their exploitation as often they could not sell their produce at a fixed or suitable price, a reasonable rate. The traders with the bargaining power of money in their pockets called the shots. This was why the APMC Act(s) both contextual and specific to states were put in place in and around the 1960s to bring an end to this exploitation. The protesting farmer in the film also took the example of Bihar, where the APMC Act was scrapped in 2006. The farmer stated how small farmers in Bihar are now forced to sit on the roadside to sell their produce for a pittance.

This aforementioned abolishment of the Mandi system becomes all the more significant when considered with the second on Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services. Through the said bill, farmers were provided with the means and protection to create their own farming agreements by allowing the farmers to interact with the private sector and fix their own prices for goods and services. As pointed out by the protesting farmers, the said bill, without APMCs to fix prices, would have resulted in small farmers being pushed around and eventually be pushed out of the agricultural sector by corporates. In addition to this, the farmers especially expressed concern regarding those marginal farmers, unaware of their rights, who will not be able to haggle with big companies. As per the protesting farmers, this bill would have served as a death warrant for farmers. Notably, the protestors were especially critical of the ignorant logic of the ruling government to encourage online trade in rural areas where even electricity is hard to come by.

The film showed the protesting farmer then explain the third law, which dealt with the Essential Commodities Act. The ECA Act, which was originally created in 1955, prevented the hoarding of certain essential commodities to prevent manipulation of stock. It also imposed a hoarding limit to keep the prices from surging. However, the Law that was introduced by the Narendra Modi-led government contained provision that allowed the Union government to regulate essential food items such as cereals, pulses, potatoes, onions, edible oilseeds and oils under extraordinary circumstances such as war, famine, extraordinary price rise and natural calamity.

As per the farmers, the same would have allowed for traders to hoard such products and also affect food prices which in turn will hurt farmers’ sales. Consequently, the hording traders could then have refused farmers selling such products.

As the protesting farmers explained these three farm laws separately and together, it became clear that the ruling government did not introduce the same with the interest of the farmers at heart. Rather, these three laws would have brought in changes that would only benefit corporate farmers, leaving behind marginal and poor farmers.

After explaining these three laws, the protesting farmer in the film stated that this issue and the concerns being raised will not remain limited to the farmers but will also affect the common man as when hoarding of commodities will take place by corporates, the price will increase. Emphasising the same, the protesting farmer had stated that “we are not only protesting for us, but also for you.”

A protest not in isolation:

The footage from the protest site demonstrated the fervour with which the farmers have been demonstrating at the borders of Punjab and Haryana, where they were sitting in protest after being prevented from traveling to Delhi by the state and union governments. As Haravoo put it, “When you are there (at the protest site), you become an active part of the celebration of democracy”.

A comforting image of diversity: Sikhs, Muslims, and Hindus dining together; Tamils, Marathis, and Punjabis holding hands with Kharibolis and Kannadigas; Haryanvis and Punjabis sleeping together beneath their tractor trailers, putting their long-standing river water dispute behind them. The film brings forth a picture of the farmers’ tenacity and resolve to raise their voice.

The film also highlighted the many tactics that were adopted by the Union government as the farmers’ protest were going on. From only speaking to selective pro-government groups of farmers and refusing to speak to others, and attempting to break the alliances of the many farmer unions, to bad-naming and discrediting the whole farmer’s movement. The film contained the derogatory and shameful words used by the senior Bharatiya Janata Party politicians against the protesting farmers. From calling the farmers “misguided” and “mislead”, blames were put on “tukde tukde gang”, “radical ‘khalistani’ elements”, “infiltrating Leftists and Maoists” of encouraging the said protests. A narrative that the farmers have not been able to understand the farm laws was put forth again and again.

The movie demonstrates how the protesters, who were unfazed by the hateful propaganda running against them and their Sikh community, continued with their protests. At one point in the film, a protesting farmer could be heard screaming that “Modi says that we are not farmers. We are not farmers! There is an insecticide called Lambda 5%, apply it on us and the BJP Ministers and then we will find out who are farmers? There is itching for three days when that insecticide touches the skin!” The scene depicted the indignant mood of the protesters, who were well aware of the statement being made against them by the Modi leadership nut were still willing to put up a strong fight.

In addition to the leadership, the voices of regular farmers play a significant role in the movie, demonstrating how even the tiniest landowners as well as women farmers were supporting and participating in the protests. The film showed how food was being prepared by farmers throughout the protests. The normal daily lives of the farmers from the protest site could be glimpsed through the film with scenes of a group of Sikhs praying reverently; protesters waiting in line for the food served by the langar, a community kitchen; men and women flipping rotis on makeshift stoves and such.

Dissatisfaction with the Modi government and its pro-corporate agenda was evident throughout the film. It is essential to note that criticisms and statements by experts and economists also formed a part of this film. P. Sainath, winner of the Ramon Magsaysay Award and India’s foremost agrarian affairs journalist, succinctly criticised the three legislations in the film by deeming them to further the capitalistic agenda under the guise of reforms by stating that “These laws are pretty much an extension of a process that this country embarked on in 1991 in the name of the new economic policies and economic reforms which is the worst abuse of the word reforms. These are laws that are tailor-made for specific Indian capitalist groups. In fact, I would suggest that some of their representatives had a hand in drafting [these laws] because even before the laws were adopted in Parliament, some of the groups were already building silos for storage [of agricultural produce].” In fact, Modi had stated that the laws were “essential for making of a new India”.

The infamous tractor parade and the reigniting of the protest:

The film also shows clips on the infamous tractor parade that was taken out by the farmers on Republic Day of 2021. The film showed how the farmers were given permission for the said tractor rally only on January 24, leaving the farmers with not much time to prepare for the parade. As we all remember, the said tractor parade took a violent turn when Delhi police stopped the farmers from continue with their parade on the specified path. Chaos ensued as a renegade group of farmers were then seen bursting through the security cordons at the Red Fort and hoisting the Nishan Sahib, the Sikh religious flag. One death of a protestor had also resulted.

The film showed the sombre mood that prevailed after the violent incidents amongst the protesting farmers, especially the elder farmers. An intense distrust had suddenly enveloped the farmers at the protest sites after the events of January 26. While the farmers maintained their stance about the protesting farmers not being involved in the violent incident, this gave an opportunity to many opposing the movement, especially the pro-Modi mainstream media, to question the continuation of the protest. One faction of the farmers protesting formally withdrew from the protest. The state police also stopped providing electricity and water at the protest sites. One particular instance of police forcefully asking the protestors to empty out a protesting site at night was also shown.

The movement could be seen getting scattered. The change in momentum came with one interview of Rakesh Tikait, leader of the Bhartiya Kisan Union (BKU), where he could be seen crying over the dim situation of the ongoing farmers’ agitation. One could say that his tears galvanised people, as on the next day a large number of farmers and other supporters came to the protest site at the Delhi-UP border from not just his home state of Uttar Pradesh but from Punjab, Rajasthan and Uttarakhand as well to show solidarity with the movement. The film had showed the multitude of green-and-white caps and flags of unions and tricolours planted on tractors, symbolic of the unions fronting the battle, dot the highway at Ghazipur as the farmers’ protest gained forced once again. Notably, well over 650 farmers had been martyred during the farmer struggle 2021 all over India. As provided by director Haravoo, this documentary was dedicated to all the farmers who lost their lives in the course of their gritty protest.

A victory, but at what cost?

The documentary film ends with chilling scenes of the Lakhimpur Kheri massacre that broke out on 3 October 2021, where eight people, including four farmers, were killed. The car that killed these eight people was allegedly driven by Ashish Mishra, the son of Union Minister of State (MoS) for Home Ajay Mishra ‘Teni’. Many were injured in the violence. As we all remember, the group of farmers were protesting with other farmers against the three farm Laws at a dharna near Tikunia, which is Union Minister Ajay Mishra’s paternal village in Lakhimpur Kheri. The said protest was ahead of an event were Uttar Pradesh Deputy CM Keshav Prasad Maurya was to be the chief guest. The demonstrating farmers had planned to “show flags to the deputy chief minister” and had also reportedly “staged a demonstration in front of ‘Monu’ aka Ashish Mishra’s car when he was going to receive Keshav Prasad Maurya.” This is when the Union minister’s son allegedly “ran his car over the protesting farmers” stated the farmers.

After the visual of the violence, the film ends by providing that the three farm laws were repealed by the Modi-led government. On November 19, the day of Gurupurab, the biggest Sikh festival, PM Narendra Modi had announced the repealing of the three Farm Laws. The announcement had come exactly a week before November 26, as the massive farmer led protest and in various forms across the country, would have completed one year. During the said announcement, PM Modi also added that the Farm Laws were passed with “good intentions” and for “welfare of farmers, especially small farmers, in the interest of the agriculture sector, for a bright future of ‘gaanv-gareeb’,” however the government has not been able to convince farmers and “a section of them has been opposing the laws, even as we kept trying to educate and inform them.”

More than 2 years later, where do we stand?

Haravoo is a recipient of the National Award for his debut feature film ‘Bhoomigeetha’ (Song of the Earth) in 1997. In an interview with the Frontline, director had provided his opinion on the protests and stated that the top leaderships of the BJP both in states and at the Centre had failed to grasp the seriousness of this peoples’ movement. The farmers’ protest is a historic movement and has many lessons for democracy. The repealing of the farm laws was a result of the sheer will power of the farmers sitting on protest, under adverse weather conditions, and dealing with infrastructural challenges while being contained behind barricading. But, as we all know, repealing the farm laws was one of the demands. The other demands are the legalisation of Minimum Support Price and the repeal of the Electricity Amendment Bill and other laws as well as exploitative labour codes.

Today, the same farmers are leading another protest in the face of same, if not more extreme, adversities. The Samyukta Kisan Morcha- Non-Political and the Kisan Mazdoor Morcha announced ‘Delhi Chalo’ march by more than 200 farmers’ unions. The major objective behind this said protest is to demand from the union government a delivery on the farmers’ long-standing demand of enactment of a law to guarantee a minimum support price (MSP) for their produce. Besides a legal guarantee for minimum support price (MSP), the farmers are also demanding implementation of the Swaminathan Commission’s recommendations which provided for safeguarding the interest of small farmers and addressing the issue of increasing risk overtaking agriculture as a profession. In addition to this, pensions for farmers and farm labourers, farm debt waiver, withdrawal of police cases and “justice” for victims of the Lakhimpur Kheri violence also form a part of the demands made. As stated by Mandeep Punia, a local journalist from Punjab and Haryana, they farmers have also raised a demand for 200 days’ daily wage and Rs 700 per daily wage for MNREGA (Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act) workers.

The month of February 2024 saw the strong resurgence of the farmers’ movement in the country, accompanied by an equally repressive push-back by the BJP regime. State actions in the form of internet bans and censorship, tear gas and firing of rubber pellets, and attempts to prohibit the farmers from exercising their right to protest were once again seen.

On March 14, visual of farmers in large numbers in the “Kisan Mazdoor Mahapanchayat”, being held at Ramlila Maidan, Delhi, emerged. At this protest, almost 37 farmer unions under the umbrella of the Samyukta Kisan Morcha (SKM) gathered in Delhi to press the union government to accept the demands of the farmers. Along with this, they also seek justice for the death of the 22-year-old farmer Shubhkaran Singh, who was killed during clashes with the state police.

Thus, the Indian farmers’ fight is far from over.

Details of the farmers’ protest 2024 can be accessed here.

Related:

Farmers protest: Documentary ‘Kisan Satyagraha’ barred from Bengaluru film fest

Farmers’ Protest: Physical repression, prohibitory orders, Delhi entry blocked – Déjà Vu?