Images of resistance

The three images below teach us how society is transformed – by the courage and determination of the oppressed and marginalized; by tears of rage, and by stony cold resistance in the face of violent retaliation by entrenched power. It is not that these pioneers were fearless, but that they acted despite their fear.

The first shows Kairali TV camera-person Shajila Ali Fathima, tears running down her face as she continues filming the vandalism of Hindu right-wing mobs over the Sabarimala issue, despite being threatened and physically attacked (her neck was hurt, and she has since been advised a cervical collar and rest).

The second shows fifteen year old Elizabeth Eckford walking steadfastly past the hostile screams and stares of white segregationists on her first day of school in 1957, after the US Supreme Court outlawed racial segregation in schools.

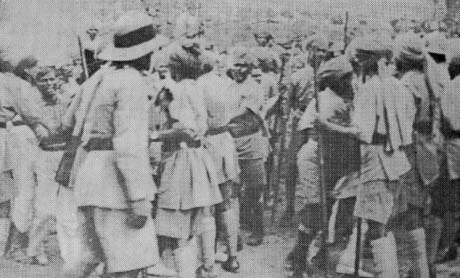

And the third shows the Kalaram Temple satygraha, led by BR Ambedkar and BK Gaikwad in 1930, to fight for the right of Dalits to enter the temple. Almost nine decades later, Dalits still face immense hostility and violence towards their right to worship and participate in temple festivals.

Women are activists, men are devotees

The Supreme Court today decided to reserve judgement on the 48 pleas around the review petition on its previous order permitting Sabarimala entry for women of menstruating age.

Meanwhile, let us reflect on the curious distinction made by the media in the coverage of this issue, as well as by Kerala Ministers and police officials. Women attempting to enter the shrine following the Supreme Court order are termed activists, the men mobilized by Hindu right-wing organizations who violently stop them, are termed devotees.

Thus.

Several Kerala ministers on Friday said the Sabarimala temple should not be a place for “activism” even as three women attempted to trek to the hill shrine.

Chased away from Sabarimala by angry devotees, 11 women activists vow to return

The Kerala Police has said it would not be able to provide protection to women activists attempting to enter Sabarimala, Malayala Manorama reported. The special officer posted at Sannidhanam, the temple, has submitted a report to DGP Loknath Behera in which he wrote, “It is obvious that most of them are looking for publicity. The police should be allowed to dissuade them from going to the shrine.”

How does this distinction work, exactly? Why are women trying to enter Sabarimala for worship, “activists seeking publicity”, while thousands of men mobilized explicitly for the purpose of blocking implementation of Supreme Court orders, “devotees”? Have these men all observed the 40 day mandala vratham , which involves rigorous penance, including celibacy, for 40 days? And why should we characterize as devotees, men who, on hearing a rumour of a woman below 50 entering the shrine, “planted themselves on the sacred 18 steps, raising fists and shouting slogans”, with none of them carrying the irumudi, a bundle carrying offerings, on their head, which is the ritual custom. Only devotees carrying irumudi are allowed on these last 18 steps to the deity’s sanctum. These men without irumudiincluded a Travancore Devaswom Board member and an RSS leader.

So much devotion towards protecting the deity from other devotees!

(I am reminded of the famous words of Vivekanda, recounting his distress at the thought of the desecration of the Kshir Bhavani temple by Muslim invaders, and his belief that had he been there, he would have laid down his life to protect the Mother. Thereupon he heard a voice that asked him, “Do you protect me? Or do I protect you?” After this, he said, he was but a child before Her.)

Law versus faith

Justice Indu Malhotra’s dissent to the Supreme Court judgement centrally made the point that courts cannot impose their rationality on religion.

In my personal opinion, social transformation is best brought about by political struggles rather than from above by the law, but the oppressed do not have the luxury of waiting for that moment to come about. Just as BR Ambedkar used both weapons, state intervention as well as political struggle, challenges to heteropatriarchy have often had to take recourse to the law, especially when the structures of heteropatriarchy and brahminical patriarchy (as feminist historian Uma Chakravarti has termed it) are upheld by the law itself. Laws on marriage, laws on sexuality – the law often encodes popular prejudice and existing power structures and this is why the struggle has to be at both levels.

Let us also state right away that temple entry is not the beginning and end of brahminical patriarchy or caste oppression, but it is a significant movement which even Dr Ambedkar took seriously. Feminists who may not be believers therefore, nevertheless support temple entry for Dalits and women, as an issue of democratic access to all spaces. (Just as feminists who may be pacifists would still support equal entry for women into the armed forces, as into any public domain).

But the Supreme Court judgement did not overturn faith, it overturned an earlier Kerala High Court judgement of 1991 on a petition by 24 year old Mahendran, which directed the Sabarimala Temple Trust to prohibit entry of women of menstruating age (between the ages of 10 and 50) into the temple. Thus it was the Kerala High Court (the law) that banned entry of women, directing the temple trust (the keeper of the faith), to ensure this, and asking the Kerala government to use the police force to enforce the order to ban entry of women to the temple.

Why was this court order necessary? Because in fact, women were going to Sabarimala. Writer NS Madhavan claims that an “informal ban” may have existed, but women routinely went to the temple, especially for the ceremony of the first food given to infants (choroonu), but also on other occasions – from the Maharani of Travancore in the 1930s to the young woman whom Mahendran saw trekking up to the shrine. T K A Nair, a career civil servant and adviser to former prime minister Manmohan Singh, said his own choroonu was performed at Sabarimala with his mother feeding him in her lap in 1939. By the mid 19th century, it seems the informal ban existed, according to a British Survey report, but that is already well into modernity. Hoary tradition is not established by a 19th century report.

OB Roopesh has written about Sabarimala in the context of what he terms “templeisation”. This he describes as

a process of converting myriad forms of worship places like kavus [sacred spaces near traditional homes of various non Brahmin and Dalit caste communities in Kerala], to the Hindu (or Brahminical) temple form.

Roopesh is critical of Devaswom Boards that remain bastions of upper castes, and appointment of Backward Caste and Dalit priests is met with savarna resistance. The first Dalit priest in a Devaswom Board was appointed only in 2017, and he faced severe protests. Interestingly, says Roopesh, this Dalit priest is also opposed to women’s entry into Sabarimala.

(‘Sabarimala Protest. Politics of Standardising Religious Pluralism’, Economic and Political Weekly, December 15, 2018)

If one indeed cares for tradition, there is sufficient historical evidence to suggest that Sabarimala was a Buddhist shrine, and that Ayyappa was Nilakantha Avalokiteswara depicted in the Buddhist Puranas. The chant of Sabarimala pilgrims Swamiye sharanam Ayyappa echoes the Buddhis chant Buddham sharanam gachhami. Rajeev Srinivasan who has been on the pilgrimage several times, suggests that prior to its Buddhist incarnation, the temple was an early Dravidian Saivite centre, and has thus been a sacred spot for 3 to 4 millenia.

Rajeev cites Devakumar Sreevijayan who has an interesting take on the myth of Ayyappa being the son of Vishnu and Siva – that this suggests a reconciliation between Saivite and Vaishnavite Hindus. Unlike other parts of the South, therefore, he says, where the two were often in conflict, Kerala has typically seen harmony between them.

Jitheesh PM has surveyed scholarship on the origins of Sabarimala and Ayyappa, and finds that it is difficult to establish Ayyappa in the Puranic texts, and nor is his worship found North of the Vindhyas. On the other hand, it is non-Brahmin influences on the historical evolution of Sabarimala that Jitheesh finds. The relationship of Ayyappa with the horseman god Ayyanar of Tamil Nadu is one such influence. According to T.A. Gopinatha Rao whom Jitheesh quotes

Ayyanar is basically a village tutelary deity, worshipped by the lower castes. There are iconographical similarities between the two deities and etymologically too it appears to be feasible.

One can see the gradual ‘templeisation’ (to use Roopesh’s term) of Sabarimala over the centuries. Like every religious practice in India, Sabarimala too has dense and living histories that are sought to be frozen by the current “owners” of religion.

This brings us to another of Justice Malhotra’s arguments, accepting the claim that Ayyappa worship is a sect or a separate religious denomination because it follows Ayyappa Dharma, and can therefore have its own beliefs and practices. If anything, what we see is that what was a non Brahminical shrine is gradually absorbed into Brahminical Hinduism, losing any claim to be a separate sect.

Overall, it seems to be less tradition and more modernity that imposed the ban on women. Only in 1972, according to NS Madhavan, was a more strict ban sought to be imposed. At any rate, there is considerable debate on what transpired regarding women at Sabarimala prior to 1990, when Mahendran approached the courts.

One of Justice Malhotra’s other points of dissent has to do with the petitioners (Indian Young Lawyers’ Association) who she said were not directly affected by the ban, as they were not devotees. However, from their names (Bhakti Pasricha Sethi, Prerna Kumari, Sudha Pal, Lakshmi Shastri and Alka Sharma) they are all Hindu women, and there is no reason to believe they would not climb Sabarimala if they could. Of course, Sabarimala is one of the few temples that does not prohibit entry on the basis of caste and religion, so their Hindu identity is not really relevant. One does wonder though, how their devotee status (or lack of it) was determined.

After all, Mahendran was simply a private individual who saw a photograph in a newspaper of women at a choroonu ceremony, claimed his sentiments were hurt and wrote to the court. His letter was turned into a PIL. He was then supported by the Nair Service Society and the Ayyappa Sewa Sangham. Further, taking into consideration his financial state, the court even posted a lawyer for him.

But Mahendran, being a man, is a devotee, and the petitioners of the Indian Young Lawyers’ Association, being women, are only activists, even to Justice Malhotra.

Menstruation and seduction

Justice Malhotra also rejected the plea that excluding women of the ages 10 to 50 amounts to untouchability, because all forms of exclusion do not constitute untouchability. In addition she stated that all women as a class are not excluded, only women of the age group 10 to 50. It is true that untouchability as a practice cannot simply be equated to all forms of exclusion, because the full horror of untouchability, the institutional and cultural dehumanization of a section of people identified by birth, is lost by analogizing with exclusion more generally.

However, Justice Malhotra’s reading fails to touch upon the significance of that age group – on the assumption of menstruation as polluting and the status of women of a certain age as threats to male celibacy, as Ayyappa is claimed to be celibate, a Brahmachari, by those opposing the entry of women.

Let us not here enter into whether menstruation should be considered polluting or not, although it would be important to understand when this understanding emerges. Surely not at the time of the worship of pre-Aryan goddesses of fertility and destruction, surely not in the matrilineal communities of Kerala in which the onset of menstruation was celebrated like a festival. Menstruation seen as polluting is a consequence of the expansion of Aryan patriarchal religious practices across the subcontinent.

But setting that aside, what is more interesting here is to confront the implication of the fact that that by the 19th century or so, the heterogeneous communities labelled Hindus had mostly come to see menstruation as polluting, and devout Hindu women stopped entering temples during their periods. They simply will not do so. Why then the additional precaution that no woman who could possiblymenstruate should enter Sabarimala? Are all women in the menstruating age group polluting at all times? Or is the assumption that women would lie about being in their periods and enter the temple? When devout men’s claim to have kept the 40 day vratham of celibacy and a long list of other kinds of good conduct is believed without verification, why not believe that devout women would not enter a temple during their periods? Isn’t there a powerful misogyny at work here that has nothing to do with Ayyappa worship itself?

As for the claim of Ayyapa being celibate, this appears to be a later addition to bolster the argument against women’s entry. Sandhya Ram says:

all of us in Kerala born post 1970s know of this legend solely from a movie titled ‘Swamy Ayyappan’ which was released in 1975.

Once again, a tradition of modern origin.

Interestingly, transgender people are permitted in Sabarimala. They pose no threat to Ayyapan’s celibacy, it seems. The heteronormativity attributed to Ayyapan, the progeny of two male gods, is astonishing.

The Hindu right wing activists are proud of the fact that their violence stopped the entry of women, except for Kanakadurga, a Nair, and Bindu Ammini, a Dalit.

However, even the entry of just two women was treated as a calamity. A Whatsapp message the Hindu rightwing circulated after their entry focused on the deceitful strategies the women used to be able to escape the policing being carried out by violent mobs. In the long rant, the following passage stands out:

“This is the true nature of our enemy here in Kerala….An enemy who does not even have the dignity or courage to enter through the front door, but instead, sneaks in and out of back doors like someone having an ILLICIT AFFAIR.”

An illicit affair with the deity Himself – Bhakti poets have written of the glory of this romance, of the belief that love for god cannot be held within the rigid bloodless bounds set by societal norms. Who are the real devotees here?

The movement for women to enter Sabarimala has a long history going back to earlier anti-caste movements, a history that the Chief Minister has continually recalled. The movement for dignity by Nadar women in Travancore, for example, challenging the upper caste prohibition on lower castes covering their breasts, was met with equal violence. Some converted to Christianity to escape caste humiliation. Nadar women who dared to wear upper cloths like Nair women were attacked, schools and churches were burnt.

In a significant reversal today, the Travancore Devaswom Board which manages the Sabarimala temple told the Supreme Court that it has no objection to the entry of women inside the temple and urged the people to “gracefully” abide by the apex court’s verdict.

Once women, including the current #HappytoWait-ers begin to enter the temple, we can start thinking about the fragile ecosystem of the Western Ghats that Sabarimala rests in, and the implications of increasing amenities for the flood of pilgrims expected. The sudden concern for the environment in the context of women pilgrims alone is suspicious, of course, but this is a real issue. There must be ways of regulating pilgrims, advance applications, limiting the numbers annually, not providing urban comfort, but ensuring only basic, eco-sensitive and sustainable facilities.

Kanakadurga, Bindu Ammini, and scores of other women have paid a high cost to approach their god. Many hundreds and thousands more wait in the wings. Their faith is faith too.

The Supreme Court decision thus, was not a judicial review of ancient faith, as Justice Malhotra holds, but an overturning of a previous legal interpretation of human, not divine, practices; of recent historical origin, not an unchanging hoary past.

Courtesy: Kafila.online