Mount Abu, Rajasthan: Rambha Prajapati, 54, a resident of Mount Abu in Rajasthan’s southern district of Sirohi, has kidney disease. She needs regular dialysis, a life-saving procedure without which she would succumb to bodily toxins that her kidneys cannot eliminate.

Rambha Prajapati, 54, is grateful for the Rajasthan government’s Bhamashah Swasthya Bima Yojana for having saved her the recurring cost of dialysis, a procedure she needs twice weekly. Since seven in 10 Indians have no health insurance and government hospitals have limitations, even poor Indians are left with no option but to pay for treatment at private hospitals. Ayushman Bharat, the central government’s new universal health coverage programme, must aim to reduce this burden.

The community health centre in Mount Abu has no dialysis facility, so twice a week she visits a private hospital, where she presents her Bhamashah Swasthya Bima Yojana (Bhamashah Health Insurance Scheme, BSBY) card and photo identification to undergo dialysis at no charge.

“When I fell very sick last August, I was saved by this hospital,” a visibly moved Prajapati told IndiaSpend on a recent May day, recollecting the bout of illness that had led to her kidney failure diagnosis.

Free treatment under the BSBY scheme, named after Bhama Shah, a fabled general and minister in the erstwhile kingdom of Mewar, has won the Rajasthan government Prajapati’s gratitude for sparing her the recurrent health expenses that would have pushed her family deeper into poverty. Widowed some years ago, Prajapati and her son live on the latter’s income of Rs 9,000 a month from working in a small shop during the day and offering tuition in the evening.

Without BSBY, Prajapati’s story would have mirrored that of seven in 10 Indians who seek outpatient and inpatient care from private hospitals when they fall sick because the government health infrastructure falls short. Without insurance, they end up paying from their own means (hence, “out-of-pocket” expenditure). Serious or chronic diseases that entail high expenditure push them into deep poverty–health-related expenses accounted for nearly 7% of Indian households that fell below the poverty line between 2004 and 2014, this Brookings India research paper, based on National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) figures, said.

As many as 52.5 million Indians were impoverished due to health costs in 2011 alone–almost half of the world’s population impoverished annually–FactChecker reported in December 2017.

Previous schemes unsuccessful

Recognising the imperative to protect India’s poor and vulnerable, the central government announced Ayushman Bharat, a programme covering primary, secondary and tertiary healthcare, in February 2018.

The programme aims to provide free essential drugs and diagnostic services for illnesses that do not necessitate hospitalisation (outpatient care) through 150,000 health & wellness centres, as well as an insurance cover of upto Rs 5 lakh per year per beneficiary family for hospitalisation (inpatient care), both secondary and tertiary care.

Ayushman Bharat is expected to take India towards universal health coverage, the situation when “all people obtain the health services they need without suffering financial hardship when paying for them”, to quote the World Health Organization.

To cover more than 107 million poor and vulnerable families, or about 40% of India’s population, the government claims that Ayushman Bharat will be the world’s largest government-funded health protection programme, and will have “a major impact on reducing out-of-pocket expenditure on health”.

How would Ayushman Bharat be different from previous government-funded health insurance schemes? Several such schemes have been launched since 2007, both at the state level–such as the Rajiv Aarogyasri Health Insurance Scheme in Andhra Pradesh and the Rajiv Gandhi Jeevandayee Arogya Yojana in Maharashtra–and at the Centre, namely, the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY).

None of these has significantly reduced out-of-pocket expenditure on health, this 2017 PLOS One study and this 2017 study published in the journal Social Science & Medicine show.

Previous inpatient schemes have led to more people utilising the services made available, but have failed to reduce the out-of-pocket burden of people, agreed Shamika Ravi, director of research at Brookings India and a member of the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister of India.

The lack of support for outpatient care, insufficient coverage and the inaccessibility of empanelled hospitals for rural residents have been blamed for the failure of earlier schemes, the PLOS One study noted.

One state government scheme that stands out from others is Rajasthan’s Bhamashah Swasthya Bima Yojana (BSBY), launched in 2015, which was designed to avoid the shortcomings of earlier schemes. IndiaSpend visited a private hospital in Mount Abu, Rajasthan, to see what BSBY has got right.

Outpatient spending on medicines high

While the private sector provides 75% of outpatient care and 55% of inpatient care in India, it is outpatient care that accounts for 75% of the out-of-pocket expenditure on health, as per the Brookings India research paper cited before. Of this, NSSO 2014 data show, 72% of all health expenditure in rural areas and 68% in urban areas is on buying medicines for non-hospitalised treatment.

“People’s health burden mostly arises from the purchase of medicines for frequent illnesses (such as colds, coughs and fevers) which are mostly preventable and do not need hospitalisation, and from spending on managing chronic diseases,” Chhaya Pachauli, a public health activist associated with the Rajasthan-based NGOs Prayas and Jan Swasthya Abhiyan, told IndiaSpend.

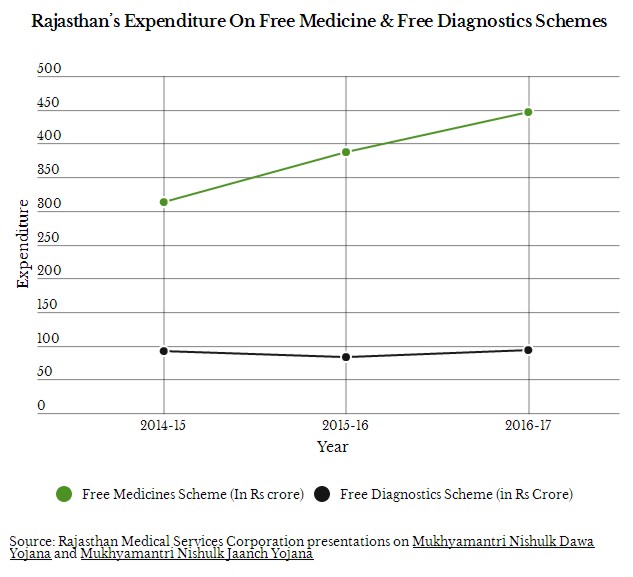

To plug this gap, in October 2011, the Rajasthan government launched the Mukhyamantri Nishulk Dawa Yojana (Chief Minister’s Free Medicine Scheme) to provide free essential medicines to all, and in April 2013, the Mukhyamantri Nishulk Jaanch Yojana (Chief Minister’s Free Investigation Scheme) to provide free basic diagnostics.

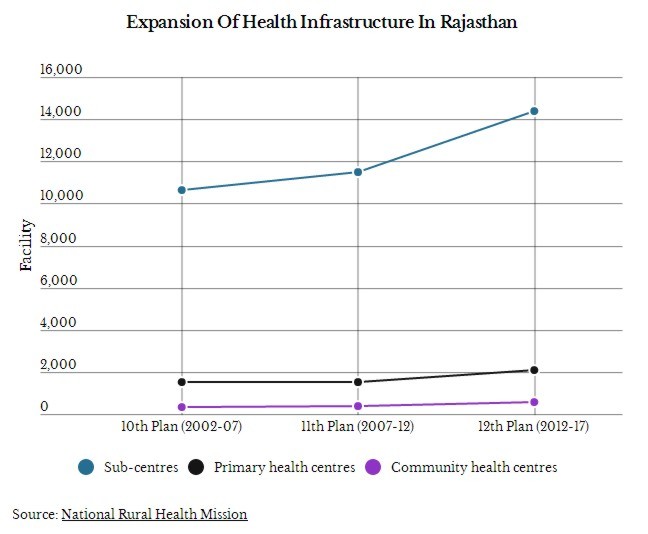

Then, during the 12th Five Year Plan (2012-17), the Rajasthan government expanded its primary healthcare infrastructure on a war footing. As a result, today Rajasthan has more health sub-centres (the first point of contact between the primary healthcare system and the community), primary health centres (PHCs, the first point of contact between the community and the medical officer), and community health centres (CHCs, referral centres for four primary health centres staffed by four medical specialists–a surgeon, physician, gynaecologist and paediatrician each) than the minimum recommended by the government for the rural population.

This seems to have worked. Nearly 80% more people accessed government health infrastructure in Rajasthan in 2016 as in 2013–eight million per month as against 4.4 million, as per a September 2017 presentation by the Rajasthan Medical Services Corporation. The government attributes this to the free medicine scheme.

However, although distributing free medicines has increased the government’s per capita health expenditure eight-fold from Rs 5.70 to close to Rs 50, the impact of this spending on beneficiaries is yet to be formally evaluated.

Anecdotal evidence is mixed. “Overall the free medicine scheme is useful for poor patients who cannot afford to buy them,” said Nishtha Singh, a respiratory diseases specialist with the Indian Asthma Care Society, Jaipur, which procures medicines at a low cost for free distribution to the needy. “Our only concern is some of the drugs we buy from the government for distribution to asthma patients are of inferior quality,” she said.

At another Jaipur charity, a hospital which also procures low-cost generics from the government for free distribution to needy patients, Anil Maheshwari, the medical convener, was of the opinion that “the free medicine scheme hasn’t made as big an impact as it could have because doctors tend to prescribe branded formulations apart from the generic medicines the government provides”.

There were 605 medicines in the essential drugs list for medical college hospitals in August 2017, 525 for district hospitals, 446 for CHCs, 242 for PHCs and 33 for sub-centres, the Rajasthan Medical Services Corporation presentation said.

Staff at government health centres inadequate

While there is no denying that the carrot of free medicines and free diagnostics has attracted more patients to the government health sector, some patients still shy away from government hospitals believing they are short-staffed and offer poor quality of service.

When Bachchi Babu Ram, 54, had a fall a few weeks ago, she travelled to Palanpur town in Gujarat, 50 km from her village on the outskirts of Abu Road, to have an X-ray taken and consult a private practitioner. At the private hospital in Mount Abu where she was later admitted for surgery for a fractured femur in April, she told IndiaSpend she believed the local CHC was short of doctors and offered poor quality of service. “Patients just lie about, nobody cares,” she said of the government hospital in Abu Road.

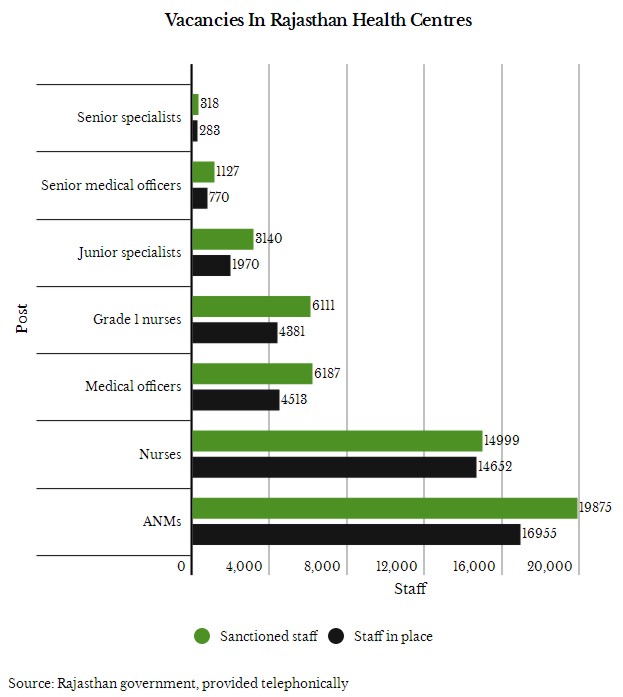

When Bachchi Babu Ram, needed surgery for a fractured femur, she got admitted to a private hospital enlisted with the Bhamashah Swasthya Bima Yojana. She told IndiaSpend she believed the local community health centre was short of doctors and offered poor quality of service. In fact, 11% posts of senior specialist, 37% of junior specialist, 31% of senior medical officer, and 27% of medical officer were vacant in Rajasthan as of March 2018, as per government statistics.

As of March 2018 in Rajasthan, 15% of sanctioned posts for auxiliary nurse-midwife (village-level female health worker), 28% posts of grade-1 nurse, 11% posts of senior specialist, 37% of junior specialist, 31% of senior medical officer, and 27% of medical officer, were vacant, according to health department data shared with IndiaSpend.

Such shortages are common, particularly in rural areas. Across India, 7% of PHCs were functioning without a doctor as on March 31, 2017, according to government data. The shortfall of specialists in CHCs was 81% and of radiographers, 64%. CHCs and PHCs together had a 22% shortfall of pharmacists and a 40% shortfall of laboratory technicians.

“Finding doctors and nurses willing to serve in rural India is challenging,” Prem Singh, State Nodal Officer at the Rajasthan unit of the National Health Mission, told IndiaSpend.

“For one, the rural and small town lifestyle puts off people, everyone wants the amenities associated with city living, and secondly, qualified doctors and specialists find jobs in the private sector in cities more academically and economically rewarding than running a simple practice in rural India,” Singh said.

As the Centre prepares to provide free medicine and diagnostics under Ayushman Bharat, finding the staff for that health network will be critical.

Singh suggested the government will bridge this gap by creating a new cadre of health professionals consisting of ayurveda doctors and nurses specially trained in preventive, promotive and curative care. “We must empower these trained personnel by giving them the right to prescribe, distribute and administer medicines that are most likely to be useful in rural areas,” Singh said.

However, when health minister J.P. Nadda introduced a bill in parliament to allow doctors from alternative streams of medicine such as ayurveda and homoeopathy to practice allopathy after clearing a bridge course, there was a backlash. Among the bill’s opponents were the Indian Medical Association, the professional association of allopathy doctors in the country, and many experts as this April 2018 report in The Quint noted.

Adequate health cover essential

RSBY, the first national health insurance scheme, covered households for expenses of up to Rs 30,000 per year, far too little to pay the cost of treating serious illnesses such as cancer.

Rajasthan’s BSBY was designed to plug the weaknesses of earlier state-subsidised health schemes, Naveen Jain, secretary at Rajasthan’s health department, who is also mission director of the National Health Mission, Rajasthan, and CEO of the State Health Assurance Agency, told IndiaSpend.

BSBY is a dual-cover scheme. The nine million families it insures get a Rs 30,000 cover for general diseases and Rs 3 lakh for critical illnesses.

At nine million, BSBY covers more than three times the 2.6 million families in Rajasthan who were entitled to benefits under the national-level RSBY, reaching 67% of the state’s 69 million population in 2012. Essentially, it covers all the families entitled to free ration under the National Food Security Act. “This top-up to the basic cover under the RSBY is beneficial,” Ravi said, adding that all states should be encouraged to do this.

The higher cover and wider coverage under BSBY seem to have set the tone for the National Health Protection Scheme, one of the two elements of Ayushman Bharat. The scheme will provide a Rs 5 lakh family cover as opposed to the earlier Rs 30,000 under RSBY.

Additionally, when BSBY was rolled out in December 2015, it was on the presumption that two existing schemes for free medicine and free diagnostics would adequately cover the two critical components of outpatient care, Jain said.

Given staff shortages at government health facilities, IndiaSpend asked Jain if there is scope to empanel private hospitals to deliver outpatient care. “That would be difficult to manage,” he said, adding, however, “[A] year into the scheme, we tweaked the criteria to include the cost of post-hospitalisation medication dispensed to patients at the time of discharge, in the package price.”

As a result, BSBY now covers hospitalisation, diagnostic expenses incurred during the seven days preceding admission, and medicine and other expenses incurred in the 15 days after the patient is discharged. However, any diagnostic expenses that the patient may have incurred prior to the seven days before admission, or any medicines they may have bought prior to admission, are still not covered.

Implementation of the scheme is monitored by measuring beneficiaries’ satisfaction levels, which BSBY gathers at the point of delivery.

Prajapati, the Mount Abu resident with kidney disease who we met at a private hospital in Mount Abu, had to certify her satisfaction with the service she received as part of her discharge procedure.

Beyond this, “aggrieved patients can register their complaints with the District Grievance Redressal Committee”, Jain said.

Experts said this is not enough. “NHPS must use the experiences of the last 15 years of implementation of publicly financed health insurance schemes across states and invest in IT systems to plug inefficiencies and mis-targeting,” said Ravi.

Essential to build-in sustainability

To be successful, a government programme has to be sustainable. To its credit, the current Bharatiya Janata Party government in Rajasthan has kept alive the free medicines and free diagnostics schemes that were conceptualised and launched by the previous Congress government.

Controlling costs without rejecting genuine claims is essential. Fair control is a key concern due to the involvement of the private sector, as this 2017 study noted while pointing at the “large private sector presence, which has perverse incentives to induce demand; and the intermediary purchaser/insurer, who has perverse incentive to reduce utilisation through cream-skimming”.

In government-subsidised health insurance, over-utilisation increases the cost of care to the exchequer, Ravi pointed out.

With BSBY, the government strictly guards against over-utilisation, which private hospitals can do by over-prescribing treatment. One of the most common examples of over-treatment by the private sector is the higher-than-necessary rates of Caesarean-section deliveries in private facilities across India, as IndiaSpend reported in July 2017.

BSBY has inbuilt rules to protect against this. For instance, 67 treatment packages including gynaecological surgeries such as hysterectomy can only be availed of at government institutes.

One way to ascertain over-utilisation is to examine whether claims under BSBY have increased or stabilised, Jain said, adding that in 2016-17, 1.8 million claims amounting Rs 985 crore were submitted, or about Rs 2.7 crore per day, but since then claims have stabilised at Rs 2 crore per day.

With this, the government’s premium payment would stabilise at Rs 1,263 per family per year for the second phase of BSBY that began in December 2017, Jain said. The premium of Rs 370 that the government had paid during the first phase–roughly a third of the present premium–had been considered too low to be commercially viable. In contrast, the NITI Aayog has indicated that premium payments for the National Health Insurance Programme would be about Rs 1,082, which is closer to the BSBY’s current premium.

Government health services must be improved

Since BSBY was launched in 2015, 88% of villages have made at least one claim, Jain said, adding that this “shows that rural people face no barrier to access care on account of the location of the private empanelled providers”.

Nevertheless, such schemes cannot be a substitute for improved government healthcare. “[P]ublicly financed health insurance schemes are not the panacea to achieve Universal Health Coverage in India. Instead, these schemes need to be aligned with proper strengthening of the public sector for provision of comprehensive primary healthcare,” the PLOS One study referred to before concluded.

As much as the government ropes in the private sector, “the primary healthcare infrastructure… [will] be necessary to provide basic health services, besides serving as gatekeeping for specialist services”, the study pointed out.

Also, universal health coverage is not simply about providing treatment, Pachauli said, emphasising that essential programmes to promote health and prevent disease, particularly for women and children, deserve greater attention. “[A]nd this can only happen if more resources are put into government health infrastructure rather than diverting them to private agencies,” she said.

Back at the private hospital in Sirohi, Bachchi was satisfied with her experience of using her BSBY card. “Ghani seva kidi,” she said, describing her experience at a BSBY-empanelled private hospital, meaning, “They served me well.”

From what has worked, and not quite worked, in Rajasthan, the planners behind Ayushman Bharat would do well to ensure that the programme offers a realistic insurance cover and adequate coverage of free diagnostics and free medicines.

It must put strict limits on the services that empanelled hospitals can provide, ensure strong monitoring on the ground, and make the redressal system easy and speedy.

At the same time, a fully staffed primary healthcare network will remain indispensable.

(Bahri is a freelance writer and editor based in Mount Abu, Rajasthan.)