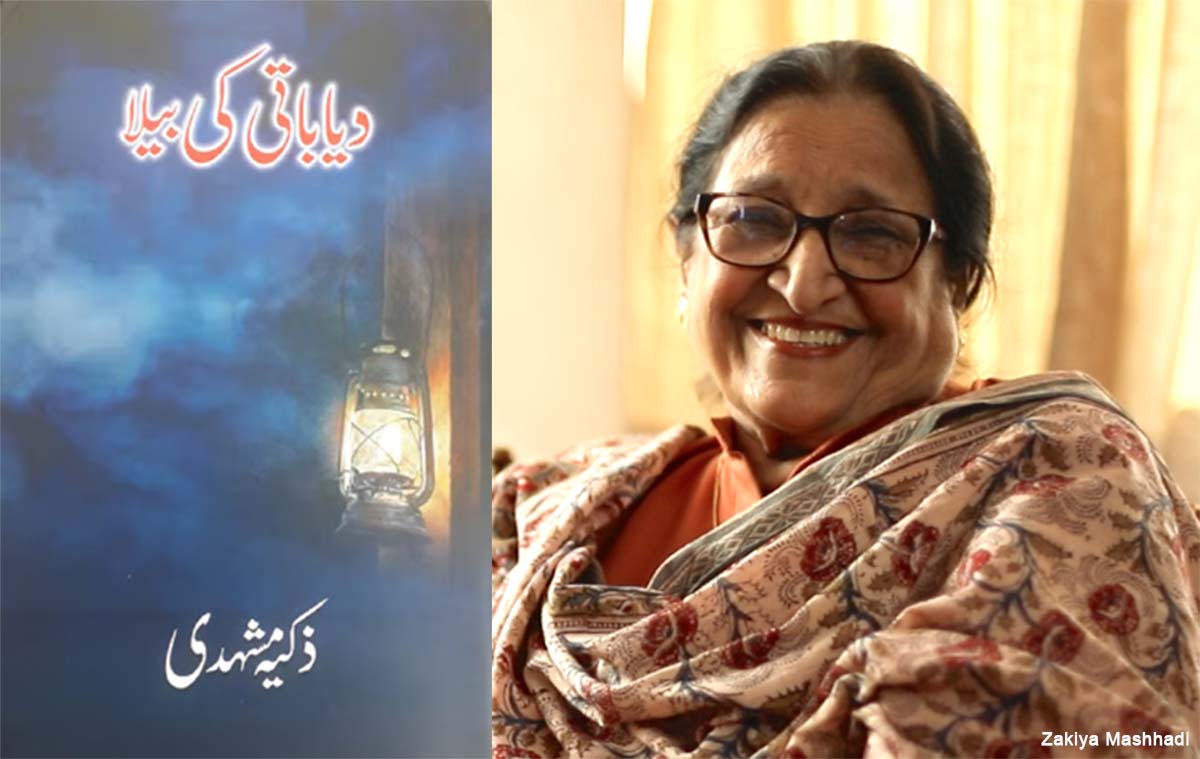

One of the latest publications of Zakiya Mashhadi (b. 1944) is a collection of brilliant Urdu short stories, Diya Baati Ki Bela (दिया बाती की बेला). The title (and opening) story in the collection is a long (almost 50 pages long) short story. My wife, Nargis is going through this collection. She insisted I read the story, leaving aside any other important assignments that I might be preoccupied with. Having read it, I realised, why the Nagri rendition of the story is urgently needed.

The title suggests something profound.

The plural, co-existence between India’s two major religious communities of the country is receiving heavy blows, kind of dying, has reached an all-time low, is on the verge of a tragic fading away, a death, this plural co-existence is being brought to its end the way dawn reaches dusk. And then the lighting of lamps is required to fight the evil of darkness.

While reading this powerful, gripping story, I recalled a passage from Qurratulain Hyder’s Urdu language family saga (autobiographical novel), Kaar-e-Jahaan Daraaz Hai (1977, p. 76). The excerpt depicts north Indian society after 1857. Discerning people may comment upon it and expand. An interplay of caste, religious communities and colonialism can be seen here.

“Sporadic Hindu-Muslim strife has begun to happen, which was almost completely absent during Mughal rule. But, despite new politics and policy (the two words are quite comprehensive), thankfully, the two communities are living in harmony as usual. Our Hindu brethren, despite close friendships do observe some kinds of social distancing and segregation, untouchability, chhut chhaat. Yet, inherent prejudice is certainly not to be found in them. We too respect their custom of segregation. It is not considered as bad and offensive. Since centuries, in my own family this is a tradition that when we invite Hindu friends at lunch or dinner, we call a Brahman to cook for them. Tolerance and mutual love is an outstanding Indian tradition. All this however may not survive the colonial onslaught”.

Apparently, if at all I have adequately comprehended the import of the story, Diya Baati Ki Bela, the responsibility (onus) is put more on the young bahu Ambika to overcome the darkness and spread light. The story is woven and embellished with all kinds of conversations, deriving much from histories and various representations of histories.

Despite different culinary practices and dietary habits, previous generations did exchange food and dine together, notwithstanding the culture of certain inhibitions and restraints. The mutually observed restraints cemented the co-existence rather than pulling the two communities apart. Some of the conversations in the story hint at the need for the Muslims to rethink their own ways of looking at the pre-colonial histories of Muslim rule in India and everyday exchanges, attitudes and conducts.

The story is very forthright about Hindu liberals having helped Muslim communalists in retaining their communal-divisive ways. Ambika’s husband, Atul, is depicted as that kind of liberal. Atul has been brought up in a liberal, tolerant, conservative, religious, yet a largely secularist family. Their pluralism derives much from their superstition too, so to say.

On the contrary, his wife, Ambika has grown up in a family insulated from Muslim culture. She therefore harbours many anti-Muslim stereotypes. She is pursuing her PhD on Kabir. Yet, she is unable to internalise the pluralistic thoughts and teachings of Kabir. Despite pursuing PhD on Kabir, she is unable to look into many social evils of Hindu society. But she is quick in finding out flaws in Muslim lives; most of the stereotypes are unreasonably fabricated and perpetuated. She assumes, no Muslim litterateur, except, Ali Sardar Jafri, ever claimed Kabir. She does not approve of widow remarriage nor does she stand against child marriage of Hindu girls. Her question against superstition among Hindu society is concerned only when this has to do with an intermingling with Muslim culture. Atul’s foster mother (a virgin widow; a victim of child marriage, a lifelong sufferer) deep regard for the tazia of Muharram is unwelcome for Ambika, even though, the five years old baby Atul could begin to speak only after he was passed under a Duldul horse.

A Hindu exclusive superstition (not associated with Muslim culture) is acceptable for Ambika.

Ambika is enlightened on Kabir by a liberal Muslim professor of Botany, fond of Cactus plants, Mannan, a retired academic, whose personal library contains every kind of creative literature, in various Indian and European languages (Sanskrit, Persian, Hindi, Urdu, English, German), besides the books on life sciences. Mannan’s and Atul’s remote ancestry converge. One of the three Kayastha brothers (engaged in legal battle for land disputes) happened to have been ostracised for having saved his life with water & food (dry gram) from a Muslim. The ostracised brother was therefore left with no choice but to convert and become Muslim. The ostracisation had also to do with a litigation battle among the three brothers for landed property. The conversion was not out of coercion or lure by Muslim society or a Muslim ruler/aristocrat. It had rather to do with the politics of real estate disputes among the three Kayastha brothers. Thus, Shamsher Jung Bahadur had to become Sheikh Shamsher Ali. Professor Mannan is a descendent of Shamsher.

Both (Atul and his Mannaan Chacha) are descendants of the said Kayastha family, having worked for the Muslim aristocracy of Magadh, who was fiercely against the Muslim League. Yet, he eventually migrated to Pakistan, in the wake of the communal violence. Before leaving for Pakistan, an issue-less widow of the Muslim family bequeathed her part of (proprietary share in) the haweli almost free of cost to Atul’s ancestors, where Atul, his father, uncles, grandfather, all were born/brought up. The haweli has an imambara. This had to be preserved, as per the will of the Muslim widow. Two generations of the women of the Kayastha inheritors do honour their promise tenaciously. Now, Ambika (the third generation inheritor of the haweli) sees no worth in preserving a Muslim heritage. She thinks, her mother-in-law and grandmother-in-law are unwise and un-Hindu to be committed to the cause of preserving this symbol Muslim heritage.

The conversations in the story are crafted with intellectual depth with the best of creative skills. Muslim rulers (the Lodis) having demolished mandirs as well as masjids (of Sharqi Sultans, Jaunpur) has been brought out in objective and dispassionate ways.

Jinnah’s hostage (yarghamaal) theory to justify his idea of Pakistan has been rebuked in a brilliant manner. The greed of grabbing assets of any issueless couples, by their kith and kin –being a deep-rooted problem in both communities – has also been brought out very well. “Yeh log giddhon ki tarah hamaarey marney ka intezaar kar rahey hain; like vultures they are waiting for my death to prey upon” (p. 29).

Pride of place and authority to the foster mother over a biological mother and the psychological dilemmas and conflicts running in the minds of an adopted child, Atul (even after having grown up) has also been depicted and articulated quite beautifully. Atul lost his mother when he was just six days old; was brought up by her aunt who was widowed the day she was married as a pre-puberty girl, whose interaction with Muslim neighbourhoods, while growing up, was quite substantive.

The Patna-based creative genius, Zakiya Mashhadi got her Masters in Psychology from Lucknow University. This specific academic training and skill finds a deft and creative application in weaving and telling her stories. This is something rare in most of the contemporary story writers.

I recall Premchand (d. 1936):

“…No single event constitutes a story unless it gives expression to some psychological truth….It is not necessary that the basis of a story should be its readability only. If a story has the psychological climax, the nature of the event to which it relates is immaterial….Of course, one does sometimes hear of events that provide an easy basis for a short story. But no event can become a story, only because of literary embellishment or a gripping narration. Events exist and so do characters, but it is difficult to find a psychological basis; once it comes up it does not take long to write a short story…”.

[My Life and Times: Premchand, An Autobiographical Narrative, Recreated by Madan Gopal (2006; pp. 212-215)].

The everyday and standardised vocabularies, idioms, sentence-framing, deep insights from cultural and historical events, metaphors, symbolism, picturesque descriptions, articulation of emotions, and every other craft of a great story-telling are plentiful in the story, Diya Baati Ki Bela.

This is a must-read story to comprehend and diagnose the current problems (of Hindu- Muslim fratricide and politically manufactured and exacerbated divisiveness) as much as the story is quite helpful in finding out workable solutions.

There are many powerful sentences in the story.

Sample these: “people throng around faqir to obtain blessings of female calf from Cow, but male baby from daughters-in-law”; “the water is as sacred and useful whether it comes out of the Lord Shiva’s long hair-locks or as Zamzam out of the fountain emerging out of the friction of the foot-soles of the Prophet Ismael”.

A story-writer like Zakiya has been kept waiting for the Sahitya Akadmi Award in Urdu. The reason may be easy to guess, fathom. Is it the rot in the institution’s jury? If the jury’s decision has to do with the politics of frustrating any messages of everyday, lived fraternity and stoking fratricide today sanctioned by the politically powerful, then this is a psychopathic reaction for an institution of art and letters. Though, great stories and story writers are hardly dependent upon an award, such awards need to honour themselves by being conferred on creative genius’ engaged in the depiction and pursuit of a plural India, something that is being aggressively eroded from public memory, and reality.

(The author is Professor of History, Aligarh Muslim University)

Related:

Nazeer Banarasi: Muslim Urdu Poet From The 20th Century Who Celebrated Indian Festivals Like Holi

Easy to Bulldoze—Fall of Patna’s Government Urdu Library and Legacy

BHU: Urdu dept HoD apologises for Urdu Day poster with Allama Iqbal’s photo