In my sixth essay, I discuss the significance of diverse perspectives on Lord Ram. I refer to Bhavabhuti’s Sanskrit play, where Lava expresses dissent, the film Adipurush, and Umberto Eco’s novel, “The Name of the Rose,” which debates the sinister nature of laughter. Our singular idea of Ram is self-destructive, emphasising the need for open dialogue and diverse narratives.

Tuesday June 20

Dear Ram

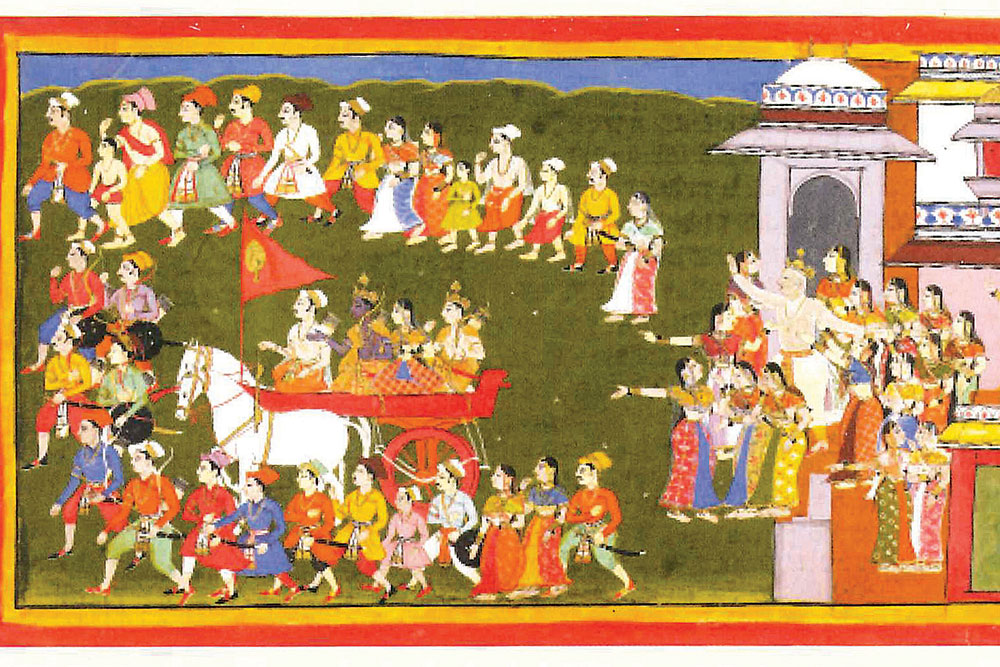

This week, a film inspired by Your Life (Lord Ram) was released in India. However, it has been noted that the film presents a limited perspective influenced by right-wing discourse. Before discussing the film and its narrow-mindedness. I seek to discuss a captivating play called “Uttar Rama Charita.” It made me ponder the significance of dissent and disagreements when portraying You as King of Men.

“Uttar Rama Charita” is an esteemed Sanskrit play written by Bhavabhuti in the 8th century CE. Based on the Uttara Kanda of the Ramayana, it delves into the events of Your life after Your return to Ayodhya from exile. Comprising seven acts, this play is widely regarded as a masterpiece of Sanskrit drama. It primarily revolves around the testing times endured by Sita, who faces criticism and doubt from some of Your subjects despite proving her purity by undergoing the trial of fire. The central conflict in the play arises when You are compelled to banish Sita due to societal pressure and the demands of your role as a king.

Within the later chapters of the play, an intriguing conversation occurs between Chandraketu, the son of your brother Lakshmana and the general of Rama’s army, and Lava, Your son and Chandraketu’s cousin. Both characters possess inclinations about each other’s identities, yet they remain uncertain. In this exchange, Lava, whom his mother (Sita) primarily raised, has had limited contact with his father (You, Lord Rama), critically assesses and questions Your actions.

Lava’s criticisms are a significant aspect of the play, as they shed light on the complexities of the characters and their relationships. Through Lava’s perspective, the play explores the themes of abandonment, the significance of maternal upbringing, and the inherent human tendency to question authority.

These criticisms contribute to the rich tradition of philosophical debates and intellectual discourse prevalent in our literature. They serve to demonstrate that even revered figures like You, Lord Rama are subject to scrutiny, and their actions are open to interpretation. This aspect of the play highlights the nuanced nature of human existence and emphasises the importance of critical thinking and questioning in understanding the complexities of morality, duty, and authority.

While You are portrayed as an omnipotent figure, the play presents an opportunity to reflect on the multifaceted nature of Your character. It invites the audience to contemplate and introspect, encouraging them to grapple with the moral dilemmas and ethical ambiguities presented by the actions of revered figures. By doing so, the play prompts deeper philosophical inquiries and enriches the overall narrative.

Should the “Idea of Ram” be confined to a single idea or imposed as a belief structure by a select few? Ideas can become dogmatic, losing their relevance to the people and community they represent.

There is a story about You as the King; You had returned to Ayodhya after defeating Ravana, You were crowned, and the city of Ayodhya celebrated the return of their prodigal son. Burdened by the responsibilities of kingship, you made a difficult decision; succumbing to the persistence of a few individuals, you chose to banish Sita from the kingdom.

One wonders what went into your mind. As a mortal human, It may be impossible for me to fathom the complexities of Your mind. They also say You were sad and lonely after ordering Sita (Your Love) to be banished from the kingdom; the victory with Ravana had left you no better. This would hardly come as a surprise; Lord, You were always gentle and often introspective about your actions.

Overwhelmed by isolation and anger, you found solace in issuing a decree banning laughter within your kingdom. The mere reminder of Ravanas’ laughter caused you immense pain, leading to this drastic decision. Unfortunately, the consequences of the ban were distressing for your subjects. Officers diligently imposed fines on those caught laughing, and severe punishments awaited those who dared to disobey the royal orders.

One day, while walking through the forest, You encountered a group of monkeys playing and laughing. Surprised, You asked why they were not afraid of punishment. The monkeys responded that they were not laughing at You but at their silly actions. This realisation dawned upon you, and you recognized that your previous orders were irrational. In a remarkable display of your true nature, you decided to reverse the ban, allowing the people of your kingdom to once again embrace laughter. This story illuminates the essence of your character, revealing your sensitivity to criticism and your willingness to listen and understand.

Contrary to Your introspective nature, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) presents a contrasting narrative with their approach to You. They impose a singular view of You as a symbol embodying virtues and moral values, advocating for a strong Hindu identity.

This situation evokes parallels to Umberto Eco’s renowned novel, “The Name of the Rose.”

The RSS’s unwavering and dogmatic perspective on You resembles Jorge’s (a priest in The Story Name of Rose) stance on laughter, ultimately leading to the destruction of the Abbey he seeks to protect. The absence of open philosophical discourse and the rigid adherence to a singular interpretation poses a risk to the broader fabric of society. It is crucial to recognize the significance of engaging in diverse dialogues and fostering an inclusive exchange of ideas to safeguard the harmony and progress of our communities.

The Name of the Rose follows the story of William of Baskerville and his apprentice Adso as they investigate a series of mysterious deaths in an abbey. William, a rational and open-minded Franciscan friar, seeks to uncover the truth behind the murders using his deductive reasoning skills. Jorge of Burgos, a blind and zealous monk, opposes William’s investigations and goes to extreme lengths to preserve the secrecy of a forbidden book on comedy. Their clash of ideologies and views on laughter ultimately leads to devastating consequences for the Abbey.

Jorge of Burgos and William of Baskerville engage in debates about laughter during their time at the Abbey. It is revealed that Jorge’s actions, including murder, were motivated by his desire to hide a forbidden book on comedy, the lost second book of Aristotle’s Poetics. Jorge sees laughter as a disruptive force threatening society, religion, and truth. He believes that all truth is known, and laughter undermines that truth. On the other hand, William argues for the virtues of laughter and sees truth as unknowable and mysterious. He believes laughter can be used to challenge falsehoods and absurdity. Jorge goes to great lengths to hide Aristotle’s treatise because it elevates comedy to the realm of art and philosophical inquiry, posing a threat to the religion and established authority. In the end, Jorge’s opposition to laughter destroys the Abbey and its library. William, in contrast, embraces doubt and intellectual flexibility, allowing him to accommodate new ideas.

The book shows Jorge’s readiness to resort to violence to protect his singular stance on laughter. Similarly, in India, there have been instances where people have been subjected to violence and coercion to conform to the RSS “idea of Ram”.The Film Adipurush seems to weaponize the concept of Ram and distort the character of Hanuman, portraying him as a seeker of revenge rather than a symbol of devotion and Bhakti ( Love)

This obsession with a singular idea leads us down a path of hatred. Hindu society must recognize that if we continue down this path, the venomous head of the snake we have unleashed will eventually bite its own tail.

We are already witnessing signs of this hate consuming us.

The idea of Ram should not be confined to a singular notion; instead, it should serve as a subject of discourse among people and communities. In this diverse narrative, Lava, the son, might criticise his father, while the nephew would come to Your defence. The monkey, representing humour, would argue in favour of laughter, while You may contemplate banning it. Valli, the aggrieved character, would say that his killing was a betrayal, and in response, You would grant him a boon to be reborn as the hunter Jara, who eventually causes harm to Lord Krishna.

On the one hand, the stories of You encompass morality, virtue, love, and loss, but they also provide space for dissenting perspectives and discourses.

In conclusion, Hindus must recognize the transformative potential of Ram as a catalyst for new discourses. The notion of a singular cultural identity, advocated by the RSS, stands as an alien concept detached from the true essence of our culture and community.

Let us not succumb to the limitations of a singular idea but rather open ourselves to the richness of discourse. In this embrace, Your legacy, Lord Ram, intertwines with our community and its diverse voices so that we can discover the path to a harmonious and inclusive future.

Yours, Argumentatively

Venkat Srinivasan

(Venkat Srinivasan is a financial professional with a master’s degree in economics. I am intensely interested in the arts, academia, and social issues related to development and human rights)

Related:

First Letter to Lord Ram: To Lord Ram, a letter of remorse and resolve

Second Letter to Lord Ram: To Lord Ram, I write again for hope

Third Letter to Lord Ram, we must talk spirituality and politics

Fourth Letter to Lord Ram, Anantatma & Anantaroopa, the Infinite Soul & who has infinite forms

Fifth Letter to Lord Ram, Perfect Lord and Imperfect Bhakthi