Following my blog “AAP’s rising star in Gujarat or guardian of patriarchy? The Gopal Italia dilemma”, I received an interesting comment from social activist Sudhir Kariyar, who works among tribal workers in Gujarat. The blog discusses how Italia, who won a by-election, wrote a letter to the Gujarat chief minister claiming that, on getting involved in love affair, young girls are being “lured” and “trapped” by wedding mafias across the state, urging the authorities to take legal action against this.

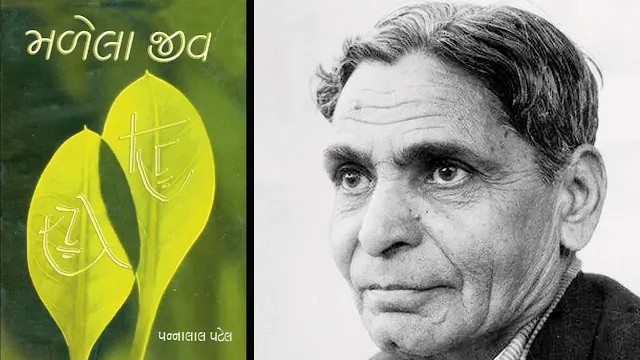

In his message, Kariyar said that the well-known Gujarati writer Pannalal Patel’s novel, written in 1931, “about the inter-caste love story between Patel and Barber caste individuals,” should be sent to Gopal Italia. He referred to a social media post by Dalit rights leader Raju Solanki, whom I have known for some time, which featured the cover of Patel’s novel Malela Jeev (Meeting Souls).

I looked up Raju Solanki’s timeline and found that he not only shared the novel’s cover but also posted a write-up on it. In his powerful piece—without once mentioning Italia by name—Solanki dismantles the AAP rising star’s contention that love marriages are an organized racket. Solanki titled his post Balela Jeev (Burnt Lives), a pun on Malela, symbolically referring to Italia.

Let me quote Solanki. He calls Malela Jeev a remarkable novel, recommending it to anyone who has not read it. The novel, he says, tells the “love story of Kanji, from the Patel caste, and Jeevi, from the Valand caste. Because of caste restrictions, they cannot marry. On the advice of his friend, Kanji convinces Jeevi to marry Dhulo, an ugly man from her village, so that she can remain close to him.”

Jeevi agrees and marries Dhulo. “A suspicious and violent man, Dhulo beats Jeevi daily. Kanji moves to the city for work, while Jeevi, weary of her life in the village, one day tries to commit suicide by mixing poison into bread. By mistake, Dhulo eats it and dies. Widowed Jeevi becomes the subject of public slander and eventually loses her sanity. Kanji returns from the city and takes her away with him. The story ends there.”

Providing historical context for when Pannalal Patel wrote the novel (1941), Solanki says, “it was still 14 years before the system of ganot (forced agricultural labor) would be abolished. The Patels were ganotiya (bonded labourers) of the landlords. In the Sarth Gujarati Dictionary, Kanbi was defined as slave and Valand as useless person. Thus, at that time, both Patels and Valands were considered Shudra castes of equal status, yet marriage between them was unthinkable. It still is today.”

Solanki quotes Kanhaiyalal Maneklal Munshi, a well-known Gujarati litterateur, as telling the Gujarati Sahitya Parishad in 1934 that among Gujaratis “men outnumber women,” pointing out that in the Bombay region, which included Gujarat, for every 1,000 men there were 900 women; in India as a whole, there were 950; but as for the Patel community, “there were only 772 women for every 1,000 men.”

Adds Solanki, “Because of this shortage of women, Patels became a gender-challenged caste. Patel youths married tribal girls, and even fairs were held to bring brides from the Kurmi caste of far-off Bihar.” Yet, alluding to Italia’s opposition to love marriages, he adds, “When it comes to their own daughters marrying for love, they oppose it.”

He wonders, “In 1941, Pannalal Patel wrote a great novel on the theme of love marriage. Who today will write about the burnt lives who oppose love marriages?”

Praising Malela Jeev in an online lifestyle journal, one Snehal Parmar writes, as a “huge fan” of romantic Gujarati novels, that in Malela Jeev Pannalal Patel “illustrates the power of true love: it always lasts, always wins, and always has won. In contrast, false love quickly fades and cannot stand up to the power of true love.” Parmar adds, “The writer expresses the difficulty of finding and sustaining true love in today’s age.”

Indeed, Pannalal Nanalal Patel (1912–1989) is renowned for his seminal novels Malela Jeev (1941) and Manvini Bhavai (1947), having written over 61 novels and 26 short story collections. He is celebrated for using the local dialect and idioms of the Sabarkantha region, making his characters and settings feel vividly authentic.

Keen observers note that the timeless tragedy of Pannalal Patel’s Malela Jeev resonates with chilling relevance in today’s Gujarat, particularly in light of recent remarks by AAP MLA Gopal Italia concerning inter-caste love marriages. Italia’s controversial statements, questioning the social harmony of such unions and suggesting they sow discord within communities, starkly contradict the core message woven into Patel’s classic.

It is pointed out that Italia’s assertion that inter-caste love marriages lead to “social and community tensions” attempts to shift blame from the entrenched caste system and its proponents to the individuals daring to defy it. Malela Jeev, by contrast, powerfully refutes this notion by demonstrating that the tension does not arise from love itself, but from the judgmental, exclusionary responses of the community.

Courtesy: Counterview