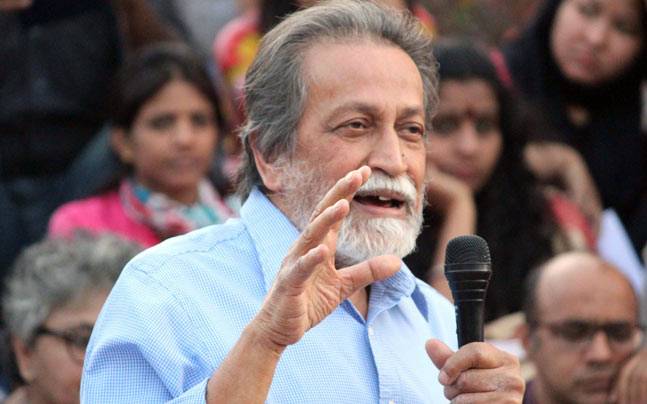

“The survival of democracy depends upon the getting rid of majoritarianism”, explained Prof. Prabhat Patnaik, prominent Marxist Economist and author, while delivering the 13th Dr. Asghar Ali Engineer Memorial Lecture on 18th November at Jamia Millia Ismailia (JMI) University in Delhi. The Memorial Lecture, chaired by Prof. Rajeev Bhargav, noted Indian political theorist, was organized by the Centre for Study of Society and Secularism (CSSS) in collaboration with the Department of Political Science at JMI. The Lecture was attended by over 200 students, academics, journalists, scholars and members of the civil society organizations. Prof. Furqan Ahmed, H ead of Political Science Dept. welcomed all the guests assembled, including eminent citizens – Mani Shankar Aiyar Prof. Zoya Hassan, Neshat Quaiser and Vijay Pratap Singh.

In the lecture titled, “Democracy versus Majoritarianism”, Prof. Patnaik, very lucidly presented a brilliant framework to understand the current political discourse in India grappling with the binary of majority and minority and the related divisive politics. Prof. Patnaik explained how majority and minority are constructed in a country and how majoritarianism seeks to limit the rights of the minority. He went on to elaborate the causes and supporting factors of majoritarianism and also how it can be and should be countered given its adverse ramifications on democracy. One of the primary reasons that the Lecture got a resounding applause and appreciation from the audience, apart from the erudite scholarship of Prof. Patnaik which reflected in his seamless delivery of the lecture, was the very relevance and direct connection it had with the socio-political and economic context unfolding in India which is marked by majoritarianism, intolerance to dissent, violence and exclusion against the vulnerable groups. Not only did he deconstruct the terms majority, minority and majoritarianism, he also suggested possible ways to arrest majoritarianism through meticulous analysis and calculations.

At the very outset, Prof. Patnaik while defining majority and minority, made a distinction between the constructed or created notion of majority and minority against the empirical notion of majority and minority. The construction is deliberate and planned as opposed to spontaneous, he clarified. He explained that this political formation of majority and minority are created to abridge the rights of the minority in the name of the majority. This abridgement or violations of the rights of the minority is attributed to the “retribution” for the “sins” that the conceptually-created “minority” is supposed to have committed or be committing. This analysis of Prof. Patnaik resonates with the demonization and hysteria created against the minorities in the country and justifying it by referring to the alleged cruelty of Mughal rulers.

But does this frenzy whipped up against the minority and the tirade berating the minority really ameliorate the condition of the majority or have tangible gains for the majority? One often wonders to what end is this hatred propagated which claims many innocent lives and tears apart the social fabric. The answer to this question was provided by Prof. Patnaik who said that abridging the rights of the minority precludes any actual or material benefit to the majority. This position is explained again by two reasons- firstly, material benefit like jobs and opportunities is not the concern of majoritarian project and secondly, the rights of the very group that is the minority that it seeks to abridge is marginalized and already disempowered. Thus, abridging the rights of the minority creates no space or more opportunities in favor of the majority. This is a point well made when the narrative that is sought to be pushed is that there is a historical conflict of interest between the minority and majority in India. Prof. Patnaik also cleared up another misconception that majoritarianism doesn’t seek to displace a privileged minority from its position of privilege and thus doesn’t have an agenda of social justice or democracy.

Prof. Patnaik pointed out that though the majoritarianism would seek the support of the majority to abridge the rights of the minority, in reality it doesn’t necessarily enjoy the support of the majority. Yet the majoritarian agenda is promoted due to some loopholes in our electoral system which enables the political party getting the largest number of votes instead of getting a majority in terms of votes to form the government. He gave an example of the BJP, which though polled only 38 percent of votes and not majority votes has still managed to form a government under this electoral system. This brings us to another question that if the support of the majority and also absolute majority in terms of votes in the electoral system are not essential for majoritarianism then how does it thrive? Prof. Patnaik dealt with this question in two parts. He said that majoritarianism arises out of conducive social context. This specific social context he points out is economic crisis and has economic roots. Though in his formulation, he precluded any material benefit for the majority from majoritarianism, he emphasized that unemployment and the precipitating economic crisis is a fertile ground for spreading the agenda of majoritarianism especially if a narrative which blames this economic crisis on the minority is given impetus.

In the second part of the answer as to how majoritarianism thrives, he explained the use of instruments which aid it. One example given already is of the lacuna in the electoral system. The others, he mentioned are the fear and insecurity amongst the people. Fear and insecurity are promoted through draconian sedition laws like the UAPA which are aimed at silencing all dissent, demands for civil liberties and human rights. This has resulted in only one sided narratives to be allowed in public discourse, couched in hypernationalism and vilification of the minorities which amplifies the silence due to fear of attracting the seditious laws. And finally, the third instrument which aids the thriving of majoritarianism, is the support of the corporate- financial oligarchy. This kind of support brings in massive funding for political parties. Prof. Patnaik gave the example of BJP which spent a reported Rs.27000 crores in the last parliamentary election, which averages to about Rs.50 crores per constituency. This nexus also controls the media. All these instruments can be categorized as control over the state. Control over the state makes it easier for the promotion of the agenda of majoritarianism which makes it absolutely crucial to select a political party with scruples to govern the country and which doesn’t use state power to the end of majoritarianism.

The most crucial part of Prof. Patnaik’s Lecture which had import on the way forward for any democracy and especially the Indian democracy which is coming to terms with the challenge of majoritarianism, was the steps to arrest majoritarianism at different levels. First measure he suggested was tactical alliances that should be forged by all political forces to uphold democracy. The convergence points for forge such unity could be the opposition to undemocratic practices, like using the CBI or the ED against political opponents, removing sedition laws and other such draconian legislation from the statute books, and curbing the menace of lynch-mobs. But at the same time, he cautioned that merely forming alliances for electoral success is not the only solution. The very conjuncture that produces majoritarianism has to be changed.

This conjuncture of majoritarianism can be changed in a number of ways. One way is to revisit the Karachi Congress Resolution 1931, which explicitly discusses the idea of the new India. This resolution was also an embodiment of anti-colonial nationalism and the inclusive nationalism on which independent India was founded on. Prof. Patnaik emphasized on the characteristics of this anti-colonial nationalism- that it was inclusive wherein it accommodates all sections of the society, it was not imperialistic where it did not seek hegemony over its people and finally it did not put the nation above its people, it gave primacy to the welfare of the people. Today India needs this nationalism and not the jingoistic nationalism which has gained prominence.

Second way to change the conjuncture of majoritarianism, he suggested, was to expand the fundamental rights given in the Constitution to include justiciable economic rights. He explained that currently, economic rights are part of the directive principles of state policy and are not justiciable. However as Ambedkar had also lamented, Prof. Patnaik observed that political democracy can’t be realized without economic democracy. To overcome this dichotomy, economic rights that ensure minimum standard of living to everyone must be made justiciable. He went on to explain the different arguments that are raised to demonstrate how economic rights are not workable, one of them being the lack of capacity of the economy to support this expenditure. But he insisted that democracy and welfare of the citizens must take precedence over the economic order which benefits capitalists.

Prof. Patnaik substantiated his argument in favour of justiciable economic rights by providing a calculation he has arrived at for raising needed finances. According to him, in order to ensure five economic rights, namely, right to food, right to livelihood, right to free quality healthcare, the right to free public education of quality at least up to the secondary level to start with, and the right to adequate non-contributory universal old-age pension and disability benefits, 11.76 lakh crores will have to be raised over and above the present expenditure on these heads. Raising 11.76 lakh crores he said was possible by implementing two measures- firstly by imposing two percent of wealth tax on the one percent of the top rich and secondly by imposing 33 per cent tax on the inheritance that is passed down each year by these one per cent of wealth-holders. He explained that capitalism demands that the capitalist earns profits himself accruing to his own merit and not enjoy inheritance. Thus, taxing inheritance is plausible way of raising the needed finance.

Finally, Prof. Patnaik cautioned that India which moving towards facism from majoritarianism and this is posing a formidable challenge in Indian democracy. In order to nurture Indian democracy, it is essential that there is an all inclusive nationalism like the anti-colonial nationalism which is starkly opposite from the Hindutva- hypernationalism. Prof. Rajeev Bhargav while appreciating the formulations presented by Prof. Patnaik, also reiterated that there are two notions of majority and minority- preference based and electoral based and these notions are temporary. Minority doesn’t imply necessarily numerical strength or the lack of it but attributed the construction of minority to the deprivation of power to shape the political culture and realization of their rights. He also emphasized on the salience of community rights based on egalitarianism in India which has layers of hierarchy.

The audience was captivated by the sheer smooth and powerful lecture by Prof. Patnaik which in all its wisdom analyzed the constructs of majority and minority in India in all its nuances. He dealt with the question of majoritarianism and the concern of its undermining democracy at multiple levels in all its complexities. This analysis of the economic root of majoritarianism in a time where the deteriorating Indian economy is impoverishing millions was well appreciated. His solutions to counter the threat of majoritarianism were innovative and promote the democratic agenda for a better India. The Lecture was very inspiring, invigorating and encouraging for the organizers as well as the audience. Dr. Asghar Ali Engineer Memorial Lectures have been delivered in the past by eminent scholars including Romila Thapar, Christophe Jaffrelot, Akeel Bilgrami and Sukhdeo Thorat.