The heart-rending spectacle of migrant workers struggling to negotiate the Covid-19 lockdown is unfolding before us in real time. The term ‘migrant worker’ however hides behind it people who have extraordinary tales to tell – tales of daily struggles big and small, Homeric journeys, the little joys that make up life and stubborn fears that linger on. Only when these accompanying details are revealed and the portrait of a man, woman or child in throes of a tragedy is sketched that the enormity of this disaster is truly revealed.

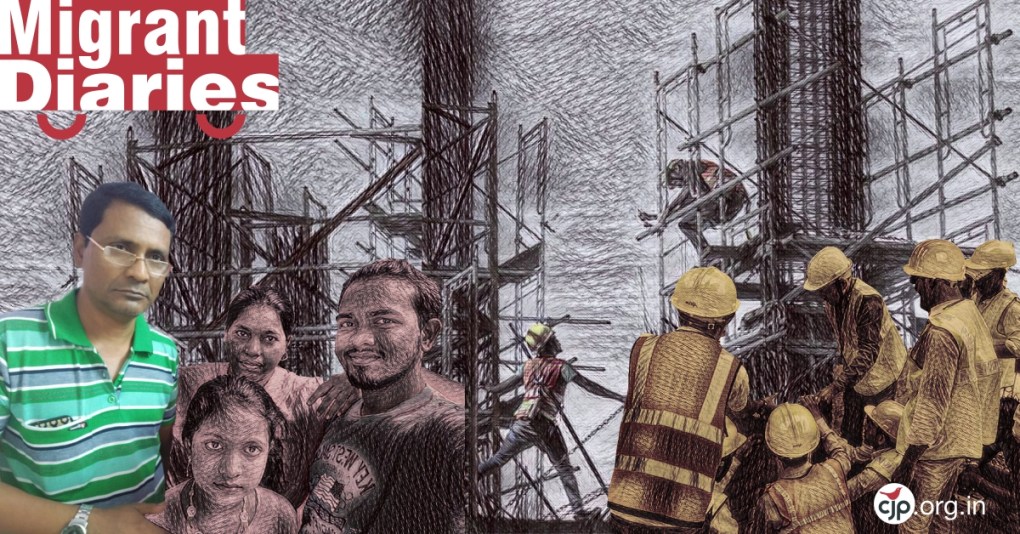

In April 2020, while responding to distress calls, CJP had helped Tinku Sheikh and five other workers in Mumbai with ration kits. On the resumption of interstate travel, Tinku went back home to West Bengal. Now in the last days of his home-quarantine, he told us what he went through. This is his story.

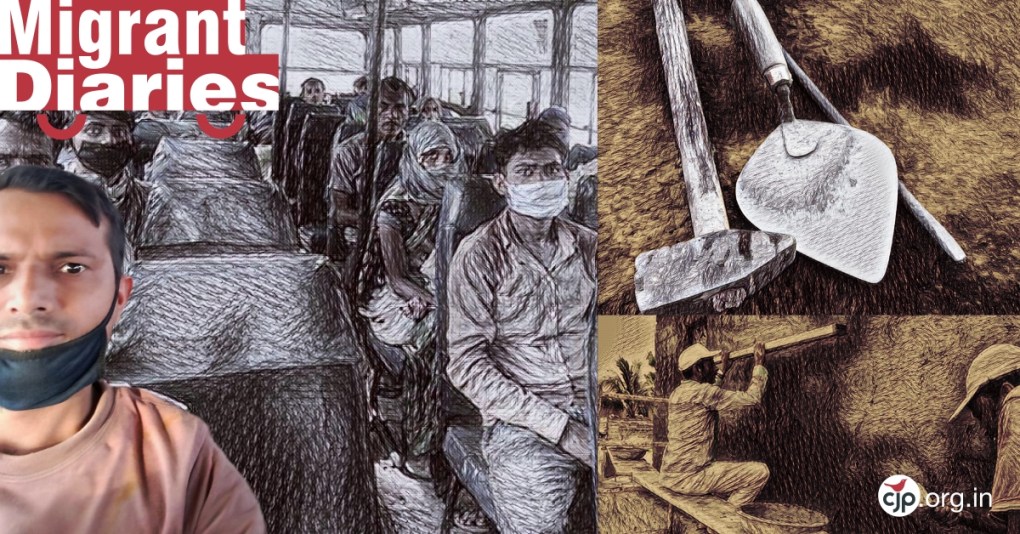

“63 of us travelled four days and four nights in an open six-wheeler truck,” says Tinku Sheikh, describing the journey he and his friends undertook from Kapurbawdi in Thane, Maharashtra to Rampurhat in Birbhum, West Bengal. “In the truck we took turns to stand and sit during the day. At night sometimes we had to pile up on each other in order to sleep. Our bags hung above us, on a rope line that we suspended across the truck,” said Sheikh describing how they all managed to fit into the small space.

27-year-old Sheikh has a young wife and a 4-year-old girl back home. His parents also live in Bengal. “If not for obhab (want), why would we leave our parent’s house and the comfort of our birthplace,” he asks. “We never owned a significant amount of land. Whatever little we had was divided between my father’s three brothers,” he explains.

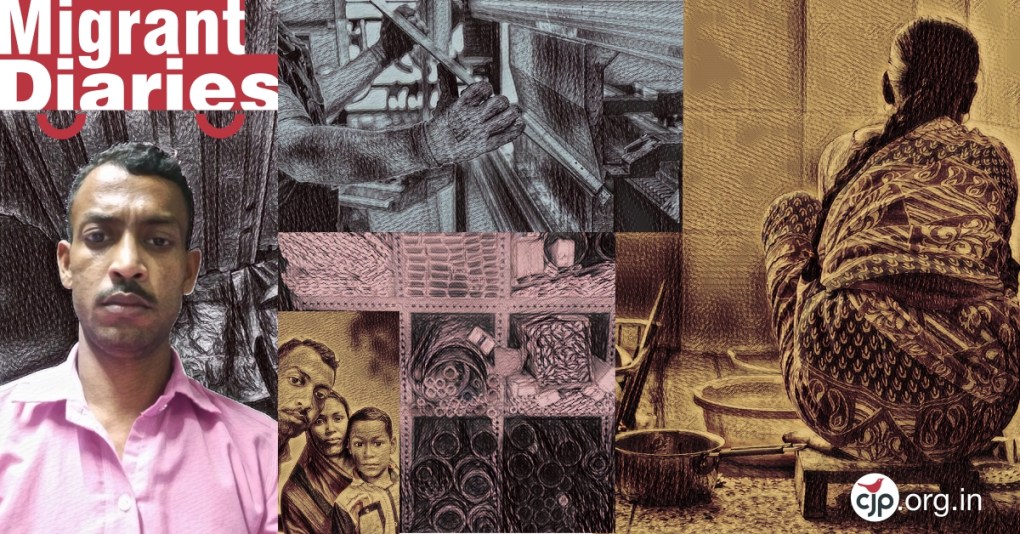

Sheikh’s wife is also unwell. “She is unable to work because of a problem in her spine. I took her to a hospital in Burdwan where the doctors said it was incurable. Then I took her to the Sai Baba hospital in Bangalore but the doctors said the same thing. We do not have enough money to take her to super speciality hospitals anywhere else,” he further elaborates upon the circumstances that led him to seek employment outside his village.

Sheikh has been coming to Mumbai for work for the last nine years. He is a rajmistri (expert mason, foreman) on construction sites. Describing his latest project, he says, “Usually we work for ‘companies’, this is the first time I was working for a private ‘party’.” Sheikh had worked on construction sites for many skyscrapers in Thane for several well-known builders. “I work for six months at a stretch and then come back home for a few months. Then I return to Mumbai for a few months and so on,” he explains.

“For the work I do in Mumbai I earn about 500-600 rupees in a day. The same work fetches 200-300 here in Birbhum,” says Sheikh as he begins to shar the math behind the backbreaking labour that keeps him and his family alive. “We go to Mumbai instead of Kolkata because we have better connections there. I don’t know anybody in Kolkata. In Mumbai I earn anything between Rs. 15,000 to Rs. 20,000 a month. Of this, I send about 10 thousand rupees back home. I need the rest for my sustenance, rent etc. This lockdown has cost me 30-40 thousand rupees. How will I ever be able to make up,” wonders Sheikh.

This year, Sheikh returned to Mumbai on February 19. “We had barely settled in, that the lockdown was announced suddenly! Six of us lived in a chawl in Girgaon. Work came to a standstill and we did nothing but sit around all day,” he recalls the early days of the lockdown. “When the lockdown was extended, we started fearing starvation. There was nothing to eat and nothing was open. In desperation I called Samirul Da (from the Bangla Sanskriti Manch). In a few days we got rations from CJP (Citizens for Justice and Peace).” Sheikh feels deep gratitude towards CJP. “I still call Teesta Madam (Teesta Setalvad, secretary, CJP) to inquire after her. I will never forget what they did for us in our times of trouble. For this I want to thank them from the bottom of my heart,” says Sheikh overwhelmed with emotion.

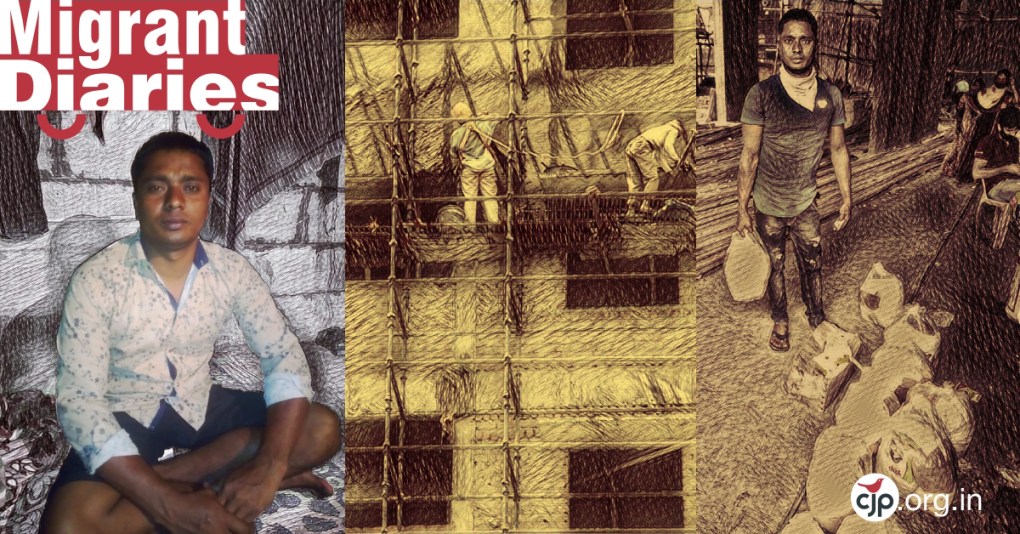

After the lockdown kept being extended, Sheikh and his friends and fellow workers started getting desperate to return home. “When we heard about the buses that were ferrying people back home, we went to the local police station. They informed us that they did not have the necessary clearance from the West Bengal government. There were no trains either. We didn’t know what to do.” But then things took an uglier turn when uncertainty turned to a clear and present threat to their lives. “One night, some men from our neighbourhood threatened us. They said ‘if any one of you gets infected with Coronavirus, no one will be spared, we will bury you alive’. They were drunk. That day we decided that we need to leave for home, no matter what,” says Sheikh, still a bit shaken from the threat.

Someone they knew offered to help them hire a truck. “If we found 60 other people to travel with us it would cost us Rupees 4200 each. We found 63, and hired the truck. On the day of the journey we set out early from Null Bazaar,” recalls Sheikh. But their ordeal was just beginning. “The only taxi we found demanded Rupees 1200 per passenger. There were six of us. We refused. A contact then called for two private cars which cost us Rs. 500 per seat. The police stopped us outside Airoli station. We had to leave the cars there itself,” says Sheikh, his words painting a picture of a world where everything that could go wrong, was indeed going wrong!

“Our pick up was now changed to Kapurbawdi in Thane. A taxi took Rs 100 per head and dropped us at Majiwada. From there another taxi took 100 rupees more and dropped us at Kapurbawdi. We arrived at 12 in the afternoon. Some people were distributing cooked food, water and biscuits. We settled in to wait for the truck. It arrived at 3 in the night,” says Sheikh.

Luckily, throughout their journey, food was never a problem. “Especially in Maharashtra, someone or the other always gave us food. Only in West Bengal we received nothing. It was a strange journey – nothing was open on the way. Though the police stopped us twice, we reasoned with them and they let us go.”

But Sheikh and his fellow travellers weren’t the only ones making this arduous journey back home. “Our driver drove slowly and other trucks easily overtook us. As they went past, I saw that they too were full of people. I cannot even tell you how many trucks there were around us. The whole road, miles before us and miles afterwards were dotted with trucks. Daily news of road accidents filled me with fear. We had also heard that the roads were bad in parts.”

Social distancing was clearly a luxury Sheikh and his fellow travellers couldn’t afford. But what about the fear of contracting the dreaded Coronavirus? “We wore masks. But we are poor people. We cannot afford fear. Only the rich can afford to be scared and sit at home. I did feel scared. I had heard about the virus. But what could I do? I had to reach home,” Sheikh says matter-of-factly.

At the Bengal border they were stopped by the police and herded into a kisan mandi. “Our body temperatures were taken and our names, addresses and Aadhar card numbers were noted down. We were there for many hours, but no food was given – only a little puffed rice and water. Soon we got angry and demonstrated against the police. Then they let us go,” says Sheikh now telling us about his ordeals in his home state.

“Back at the village we were quarantined in the panchayat school. But the living conditions were very bad. It was very hot. So, at night many of us broke out and ran back to our homes. In the morning some villagers protested outside the school and some of the runaways were brought back. I live a little away from the village so no one came for me. I have isolated myself in a room in my own house. It’s been 12 days since I came back,” says Sheikh, now finally amidst people who care about him.

He does feel betrayed by the political class. “All through the journey the only thing we discussed amongst ourselves is how nobody helped us – not the state government, nor the central government. When such a great calamity came upon us, no political leader stood up to help. We spent so much money to return home. We didn’t earn any money in the last few months. Who will compensate us? Whose fault is this,” asks Sheikh with anger simmering just under the surface. “These people are only good at extortion and bullying. When we need them, we do not get any assistance,” he finally lets out his frustration at the system.

“And now, what next,” he asks. “There is no work here. I have heard that MNREGA work has started in our village but I do not have a job card. My parents used to have one but I don’t have one. Now the offices are shut because of this lockdown, how will I get one for myself? I don’t know from where I will earn money for my and my family’s sustenance? What I do know is that if the lockdown continues then poor people will starve to death,” concludes Tinku Sheikh on a grim note, recognising that his ordeal is far from over and that uncertainty still looms large over his future.