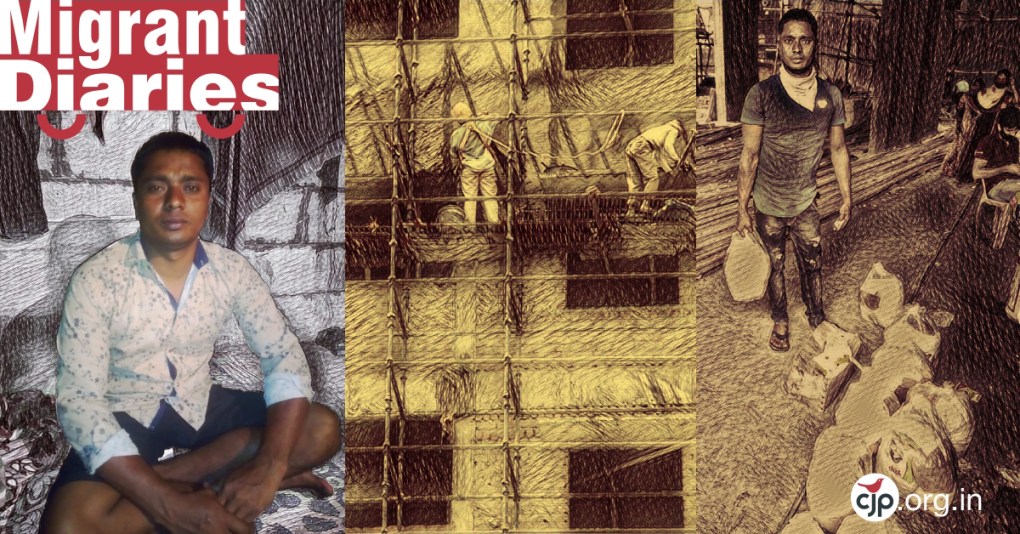

The Covid-19 pandemic could have been an opportunity for all of us as a society to showcase our most compassionate and humane side. But many employers and middle-men took this opportunity to further exploit their labourers, especially impoverished and often unlettered migrants, and push them to the brink of starvation. This is the story of one such migrant from West Bengal, Atiur Rehman.

35-year-old Rehman, a construction worker, has been toiling away in Mumbai since 2001, even as his wife, two sons, mother and sisters continue to live in Dunigram, a small village in Birbhum district of West Bengal. “My elder son is 11-years-old and he is studying in class 5. The younger one is 6-years-old and studies in class 2. My sisters are married,” he reminisces fondly about his family and village. “We have a small plot in the village and my mother does farming. She takes help from others but the income from that farm is not enough,” he says, giving us an initial insight into why he took the difficult decision to not go back home when the lockdown began.

“I am the only son and must work to support my family,” he says. Rehman feared that if he went back home, it would place a bigger burden on his family and plunging them into a financial crisis.

Rehman is a daily wager and works through agents who help him secure jobs. “We call them ‘mukhiya’ or leader, and they are the ones who hire workers like me for jobs at construction sites. They pay us on a monthly basis,” he says. Rehman manages to earn around Rs 15,000 per month. “But I haven’t got any payment for January, February and March. The agent blames it on the Covid-19 lockdown. He says the bills have not been cleared yet,” says Rehman explaining how his own penury disallowed him the luxury of leaving town in the months that followed. “I was sure I would stay put, even if the other five men I was staying with in Govandi were toying with the idea of returning home,” he says.

He remembers that one of the migrants he lived with, left for his village by truck, and two others took a bus from Majiwada, Thane. All of them paid the fare from their own pockets. He remembers an initial futile attempt at leaving town with his fellow migrants, “We had decided to go to the police station to inquire about the emergency travel forms, but the police didn’t allow us to talk to anyone and shooed us away!” Rehman still feels the anger boil over whenever he recalls how they were treated that day. He did not try to get official help again.

“My nephew and I, both, stayed back in the hope that our work will start soon,” he says, remembering being told by some people that the lockdown would end quickly. However, that did not happen. Nor did the agent give Rehman his due payments. Feeling humiliated, betrayed and exploited, Rehman decided to move from Govandi to Chembur.

“I got fed up with the situation and came to Chembur to an area where other migrants from West Bengal stay. With their help I have got work at a construction site near Surya Hospital in Santa Cruz,” says Rehman who managed to get a job when construction activity resumed. But Rehman finds it difficult to talk about the prolonged period when he didn’t have money or even food when he was still at his older accommodation in Govandi.

“After the lockdown was announced, I was anxious as nothing like this had ever happened before. None of us were prepared. We bought some ration with the money we had, but the food ran out quickly,” he says. Rehman remembers approaching a local group for food supplies, “In Govandi there is a mandal (group) who helped people with ration and food in the initial lockdown period. That was a big help for us, but soon they stopped giving food.” Rehman says he understood their limitations, “They can only offer help to an extent, not forever.”

Following this, Rehman and his group approached people in the neighbourhood. “But they were not in a position to help,” he says. Then one day, Rehman got a call from volunteers of Citizens for Justice and Peace (CJP), asking if they needed help with the travel forms. “We told them that we had run out of food and urgently needed some ration. I confessed that we had not eaten a proper meal for three days, and just survived on tea and some biscuits,” says Rehman who was overjoyed when CJP volunteers brought them ration. “There was not a penny in my pocket for three months and not a grain in my belly for three days when help arrived from CJP. We ate as soon as the food came,” says Rehman recalling how relieved he felt that day. Rehman says as his roommates had already left for their villages, and he too decided to move from Govandi to Chembur.

He shared the ration which was provided by CJP with the other migrants at the new site, “because they were also in need and how could we eat when someone else is sitting hungry near us,” says the generous man. But the ration is now running out. “I requested CJP to provide us with some more ration. We don’t need a big kit like before. Just some pulses, rice and oil,” he says.

“I want to thank CJP for providing us ration when we needed it urgently, I will remember this for my lifetime,” says Rehman who feels let down by the government. “I also want to tell everyone that we didn’t get any help from the government. They should have helped the poor in this crisis. Even when we went to the police station, they didn’t even listen to us. It is people like CJP volunteers who came forward and helped us, and I am really thankful to all of you who provided us food, which gave us strength to survive,” says Rehman.

Rehman says he is also grateful to his new friends who have helped him find work. “Our work has just started a few days ago, and we are getting payments on a daily basis,” he says, feeling relieved that now he can finally send some money back to his family. “They are also struggling in the village,” he worries.

Rehman misses his family. “I usually go back to my village during Ramzan, and come back to Mumbai 2-3 months after Eid,” he says sadly accepting why the trip did not happen this year. More than the festival celebration itself, he just wanted to be with his family. “It’s been almost a year since I have seen my family, and I don’t even know when I will go back now, because in this lockdown I have faced a financial crisis and have to make up for the losses. I just hope that my old boss gives me my pending salary as soon as possible,” says a hopeful Rehman who will send most of that money home too.

His only prayer now is that the work continues, “so that we can earn something and can manage our daily needs. I now earn Rs. 800 rupees from the past few days. I want to send Rs. 4,000 back home.” Rehman does hope to visit home for the next Eid if possible. “I want to go back home during Bakra Eid, till then I will work hard. And if needed, I will do extra work, so that I can earn enough and can celebrate Bakra Eid with my family,” says a determined and hard-working man with renewed vigour.

Related:

Migrant Diaries: Hurdanand Behara

Migrant Diaries: Laxman Prasad

Migrant Diaries: Abul Hasan Mirza