An Israeli soldier walks next to an Iron Dome rocket defense battery near the southern city of Sderot, Israel, in 2015. (AP Photo/Tsafrir Abayov)

Given this new missile interception controversy, it’s worth looking at another ongoing one. Newly-published research investigates the effectiveness of Israel’s Iron Dome rocket interceptor systems.

Iron Dome arrives

Iron Dome began operating in Israel in 2011. The systems achieved international fame during the country’s 2012 and 2014 Gaza Strip conflicts. But they also triggered controversy about their true performance.

Each Iron Dome system includes a radar, computer and several launchers. The radar detects incoming rockets. The computer then estimates the impact points. If any rockets threaten valued targets, the launchers shoot them down.

The systems cost Israel billions to develop, build and reload. The United States contributed $1.3 billion of that, and recently budgeted several hundred millions more.

Five Iron Dome systems served during Israel’s 2012 Operation Pillar of Defense against Gaza. They claimed 421 rocket interceptions. That’s 85 per cent of the rockets they engaged. Observers declared the technology a “game-changer that heralds the end of rockets.”

Nine systems participated in 2014’s Operation Protective Edge. They claimed 735 rocket and mortar shell interceptions. That’s 92 per cent of those engaged.

Skepticism about missile interceptions

However, missile interception is difficult and often doubted, as in the Syrian case. Analysts shot down American claims of intercepting Iraqi missiles during the 1991 Gulf War. Saudi Arabia’s recent interceptions of Houthi missiles are likewise under fire.

For Iron Dome, videos of interception attempts lack enough detail to confirm the rockets’ warheads were destroyed. Critics therefore have questioned Israel’s claims. One U.S. analyst argued the effective interception rate might have been 30 to 40 per cent. Another put it below 10 per cent. An Israeli critic called the system a bluff.

(The technology’s occasional missteps don’t help. In 2016, a system fired at mortar shells falling outside of Israel. Last month, one launched interceptors at machine gun bullets.)

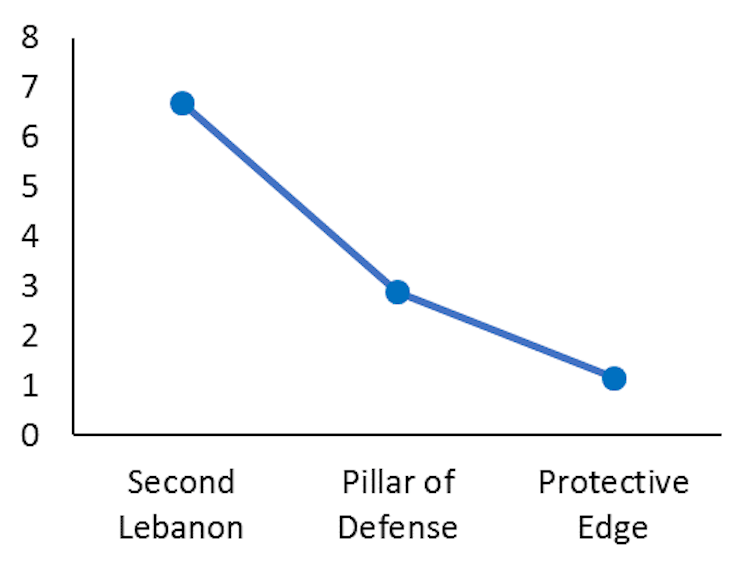

In response, Iron Dome supporters have pointed to declining property damage rates. Israel had no interceptors during the 2006 Second Lebanon War. In that conflict, the country suffered 6.7 property damage insurance claims per rocket. The rate dropped to 2.9 in 2012 and 1.2 in 2014. Supporters argued the steep decrease after Iron Dome’s arrival proved its “ironclad success.”

Average property damage insurance claims per rocket during three Israeli conflicts. Author provided

A closer look

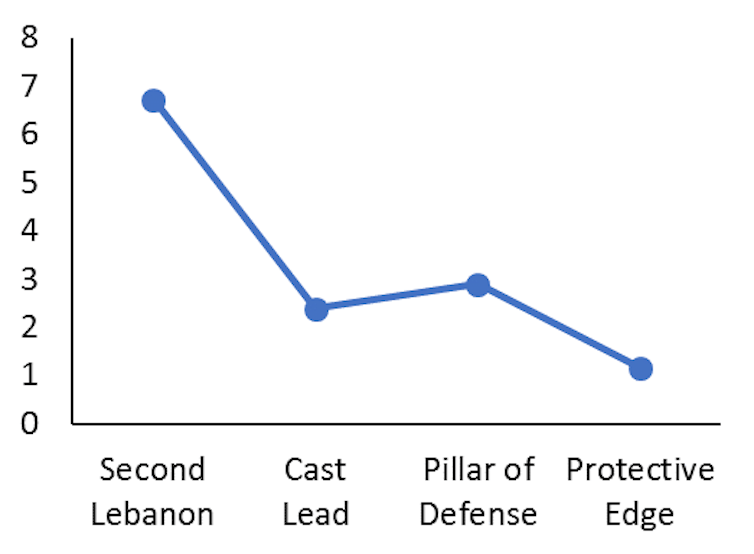

But that comparison overlooks some important details. The first is Operation Cast Lead in 2008-2009. That conflict had just 2.4 damage claims per rocket. With that included, Iron Dome’s 2011 debut coincides with slightly increased damage rates.

Average property damage insurance claims per rocket during four Israeli conflicts. Author provided

The second oversight concerns rocket differences. In 2006, Hezbollah militants in Lebanon fired thousands of Grad artillery rockets at Israel. Several hundred heavier missiles reinforced the barrage.

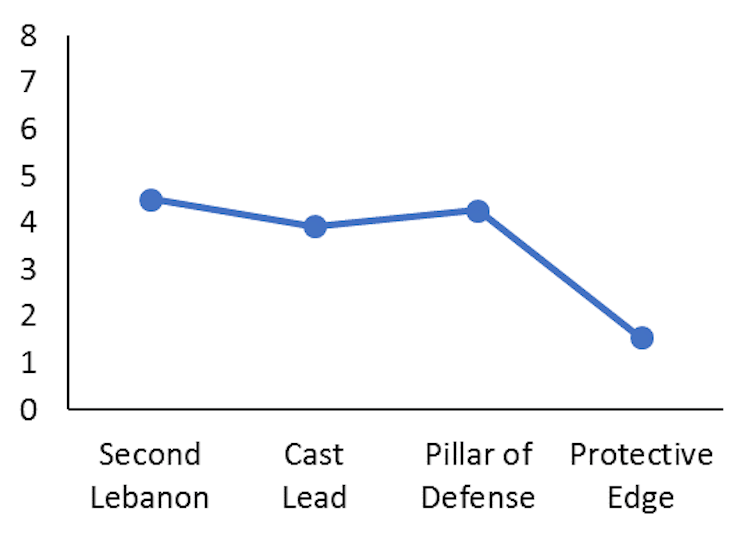

By contrast, Hamas militants in Gaza mixed Grads with smaller Qassam rockets. The average Gaza rocket warhead consequently was about half the size of those from Lebanon.

Scaling the damage rates relative to warhead weight can adjust for these differences. The damage claims per “standardized” rocket then become 4.4, 3.9, 4.3, and 1.5, respectively. The first three numbers’ closeness suggests Iron Dome had minimal influence in 2012. But the subsequent large drop implies it was very influential in 2014.

Average property damage insurance claims per standardized rocket warhead during four Israeli conflicts. Author provided

Estimating performance

My new research investigates this topic in more detail. It suggests Iron Dome intercepted 59 to 75 per cent of all threatening rockets during Protective Edge four years ago. “Threatening” means the rockets struck populated areas or were intercepted beforehand. The interceptions likely avoided $42 to $86 million in property damage. They also prevented three to six deaths and 120 to 250 injuries.

Those percentages include rockets anywhere in Israel. Therefore, the claim of a 92 per cent interception rate for only the areas defended by Iron Dome seems plausible.

By contrast, the 2012 Pillar of Defense interceptions apparently blocked less than 32 per cent of threatening rockets. They prevented at most two deaths, 110 injuries and US$7 million in damage.

The data also imply the number of rocket hits on populated areas was understated. Conversely, the number of threatening rockets seems overstated. The effective interception rate for Pillar of Defense therefore may have been markedly less than the reported 85 per cent.

Improved but not impenetrable

These results suggest the Iron Dome debate has been too polarized. The system’s initial value may have been largely symbolic. But it later become very influential.

That’s good news for Israel and its American funder. It’s also reassuring for potential Iron Dome buyers facing missile threats in other parts of the world.

Only Azerbaijan has purchased any systems so far. But the U.S. Army may buy some for short-range air defence. (Canada only bought the radar.)

However, the system isn’t “the end of rockets.” Attackers can counter interceptors by firing rockets in large batches. Indeed, Israel’s opponents keep acquiring more rockets. Hamas in strife-filled Gaza reportedly has 10,000. Hezbollah in Lebanon has 120,000. That latter arsenal would severely strain Israeli interceptors during any future “Northern War.”

Similarly, sophisticated attackers use technology to make their missiles hard to intercept. In their Syria strike, America and its allies used difficult-to-detect cruise missiles. Defenders can’t intercept what their radars can’t see.

Michael J. Armstrong, Associate professor of operations research, Goodman School of Business, Brock University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.