In light of the recent book, I Am A Troll: Inside the Secret World of the BJP’s Digital Diary authored by journalist Swati Chaturvedi which describes the working of the BJP’s media’s cell to systematically undermine dissenting opinions, we need to revisit other, seemingly innocuous, government media campaigns such as the demonetization survey and its use as a tool in bending into shape public opinion.

The demonetization survey was officially launched on 22nd November 2016 on the NM app by the government. Its purpose was to receive feedback from the people themselves on the validity of withdrawing 86 percent of the currency in circulation to address two problems: that of black money and counterfeit currency. The survey consisted of nine questions, with the tenth providing space for sharing suggestions. The questions dealt with people’s beliefs about the existence of black money in India and on its need to be eliminated. On their opinions of the government’s efforts against corruption, and more particularly, on the effectiveness of demonetization in ridding society of black money, all corruption and terrorism while creating opportunities for higher education, health care and affordable housing for all.

According to the last reports published on the survey on 1 December, 2016 by the government (Historic support for PM Modi’s efforts to make India corruption and black money free, www.narendramodi.in), the survey had polled an enormous 10.20 lakh people across 684 of the total 687 districts, being the first of such massive scale in India “on a policy or political issue.”

However, learnings from basic research methods warn us to be cognizant of two factors in surveys: the aim of the questions, and the purpose/person it serves. In the demonetization survey there lies ample data, on both accounts, and it revels something that, until now, has only begun to be discussed about Modi, his governance practices, and its tirade on dictating public opinion.

It’s all about him

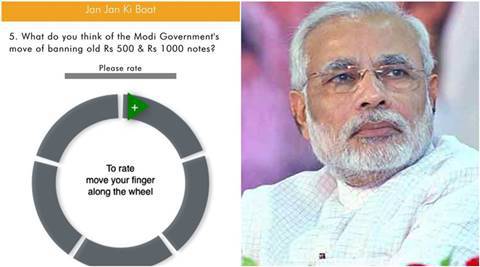

The survey was available on a free downloadable app named after the Prime Minister himself, “Narendra Modi.” Once installed, the icon on the phone had NM cemented on the screen, peering at you against a saffron background. There were no insignia of an organization or of the government infrastructure working alongside him. The survey, similarly controlled, asked about the “Modi Government’s” efforts — against corruption and on banning notes. It was “Modi,” and “Modi’s government,” against all odds. And, why is that a problem?

Perhaps because the world has witnessed several examples of newly emerging forces, such as Trump, who rely on similar claptrap we have witnessed to cash in on very real issues of public discontent, without once stopping to articulate comprehensively the arguments underlying their claims of liberation or economic prosperity. How will Trump actually revive the economy, or Modi actually address the problem of the generation of black money? In his editorial Demonetization: The morality of binaries (The Hindu, 17 November 2016), G. Sampath reflected how Modi had circumvented the problem by making demonetization (or it could be any other thing he has done) appear like a personal, moral battle against the world. In opposing his policy, you were made to feel like you were opposing a working class (national) champion, but were never left empowered to articulate why. Tools such the demonetization survey were deployed to serve this crucial function: of pushing us even further from demanding an answer.

The Purpose of the Survey

There was no reversing demonetization; the survey was not a referendum of any real consequence. The purpose of the survey was just more in the direction of the fortification of Modi. If it was indeed about people, where were the questions (and methods) to access people—their difficulties and anxieties? Of job losses, wage cuts, disinvestments, small scale industry and shop closures. The survey should have been about assessing that— the plight of the vast majority of the population whose lives are characterized by informalisation — so that the post-demonetization math could be carefully worked out — of the sectors and sections into which the presumed earned money (from newly taxable income) would be spent. Since, reports of the rise of an increase in farmer suicides and deepening agrarian crisis have emerged (The Wire, 16 January 2017) even though they made no appearance in the surveys.

Instead what we got was a set of questions replete with errors and exposing a single focus: aggrandizing the leader (and condemning the rest).

The design flaw that found most attention was the imbalanced answer options on the disagreement end. The popular one being, “Demonetization will bring real estate, higher education, healthcare in common man’s reach” A. Completely agree; B. Partially agree; C. Can’t say. There was no option to disagree.

The questions were also double barreled with two questions loaded into one; one that you might agree with and the other, maybe not. For example, “Did you mind the inconvenience faced in our fight to curb corruption, black money, terrorism and counterfeiting of currency?” There was the first question, “Did you mind the inconvenience?” Then, the second question, “Do people think demonetization addresses corruption, black money, terrorism and counterfeiting?” By combining two questions, the results had the potential of being inflated. This was also evident in the first round of results shared by the government on the 23rd of November. According to the government, 90 percent of the half million people who took the survey supported the move of banning old rupees 500 & rupees 1000 notes. Support incorporated three answer categories ‘it’s okay,’ ‘nice,’ and ‘brilliant.’ The other 10 percent were forced to resort to either choosing ‘bad experience’ or ‘can improve.’ Maybe someone thought it was a ‘bad experience,’ and ‘it was okay,’ but were forced to choose ‘it’s okay’ instead of the ‘bad experience,’ landing with the statistic that 90 percent supported the banning of old 500 and 1000 rupee notes.

Survey text books warn against another misstep – preempting a response by pushing the respondent into an inductive loop. The sequencing of the survey questions did precisely that. If you answered ‘yes’ to the initial question of “Do you think the evil of corruption and black money needs to be fought and eliminated” (99 percent did; q2), how can you then mind “[T]he inconvenience faced in our [government’s] fight to curb corruption, black money, terrorism and counterfeiting of currency?” (q8). At the end of nine questions you were locked into agreeing with everything, and also introduced to believing that “[S]ome anti-corruption activists [were] now fighting in support of black money, corruption & terrorism” (q9).

If the intention was to actually collect data that put people in the center, the questions would instead have started with ones about people’s experiences, availability of infrastructure, digital and banking facilities, assessed their means of survival, and certainly have had answer keys that ranged from ‘most likely, somewhat likely, somewhat unlikely, most unlikely, to don’t know.’ The growing crises in small industries, agriculture and among labour would have registered.

Magnifying and perhaps manufacturing opinion along with curbing dissent and criticism couldn’t have been framed in any more straightforward language. The demonetization survey is yet another example in elevating the leader of one political party above questioning. History shows that, irrespective of ideology, once that happens, it makes for a dangerous future.

Juhi Tyagi is a Sociologist and an ICAS Post-Doctoral Fellow at the Institute of Economic Growth.

Courtesy: Kafila.online