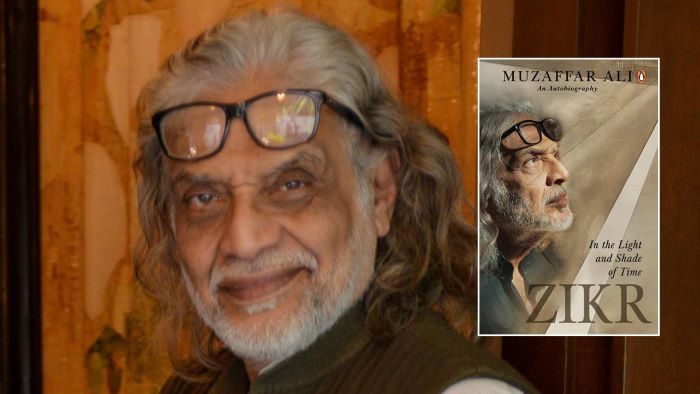

On January 25 and 26, 2024, Muzaffar Ali (born 1944), maker of some of the outstanding films in late 1970s and 1980s, such as Umrao Jan (1981, starred by Rekha), the prince of Kotwara (Awadh), visited his alma mater, AMU, with his memoir, Zikr: In the light and Shade of Time (Penguin, 2022).

In our personal interaction, I somehow felt that Muzaffar Ali was here in Aligarh to know about and feel the pulse of Muslim youth, given the dark and harsh times that India is passing through.

Discussing Zikr was, I think, just his pretext to turn into an event — so that he could have a direct interaction with young boys and girls. His self-effacing, un-assuming person, humility and modesty personified, having shed all the airs of his feudal ancestry and the celebrity-status was hardly interested in discussing his book. Rather, he was keener to get an insight into and reading the young minds. So, he was with us, first (on January 25) when he went to the Women’s College Auditorium.

The following day, the same event was held in the Kennedy Auditorium. The AMU’s Kennedy Complex is known for its extra-curricular activities; for its Drama Club, Film Club, Music Club, Literary Club, Bait-Baazi (poetry) Club, etc.

The AMU of the 1960s was one of the finest eras of AMU’s political and academic stirrings, records the historian and AMU alumnus, Mushirul Haan (1949-2018) in one of his academic essays published in the India International Quarterly (2003), “Recalling Radical Days in Aligarh”. Besides other essays for preceding decades, such as Nationalist and Separatist Trends in Aligarh, 1915-47; and Majid Hayat Siddiqui’s 1987 essay on AMU, 1904-45.

Too many of Aligarh’s Urdu memoirs paint a very rosy, romantic picture of AMU life. The only exception is the Hindi novel, Topi Shukla (1969), of Rahi Masoom Raza (1927-1992), which depicts the darker sides of the campus life at AMU.. Muzaffar Ali also avoids discussing the academics of the campus in the 1960s. May be that is because, he doesn’t have good words to say about the academics?

Muzaffar Ali did his B.Sc. (Geology, Chemistry and Botany) in 1964. He paints a rosy picture of the creative world of the Kennedy Complex of AMU. Unlike Naseeruddin Shah’s wonderfully written memoir, And Then One Day, who almost avoids painting such a picture. The memoir (1999) of the actor Saeed Jaffery (1929-2015) offers an equally romantic picture of the art, theatre and sports world of AMU, but that was long before the enviable Kennedy Complex of the 1960s. Jaffery owed it to the school teacher (later, headmaster), Syed Mohd Tonki (1898-1974).

Though, both Muzaffar and Naseeruddin acknowledge the contribution of Zahida Zaidi (1930-2011) in their creative lives. She was, “our window to art”, who inspired him “to think from a feminine viewpoint”; where “theatre and painting came together”, and that “this was an Anglicized group and made Aligarh a little more acceptable to a Westernised world”. Urdu poetry and literature were a world unto itself”; “a small cauldron of artists and one had to dive into it”; “Aligarh had the pace, leisure and culture to make people become what they wanted to be… they existed in a dream world and could read meaning into their dreams with the aid of the poetic world around”. “Rahi sahib”, who gave to us so many novels and films including the tele-serial Mahabaharata, “was indeed a mentor and inspiration”, was a “colossus of poetry”. Muzaffar Ali’s “passion for painting went back to Aligarh”, a “backbone of his creative journey” and which offered a “gift of zamana shanasi (understanding the world)”.

While interacting directly with the students in the Kennedy Auditorium, he was responding to the difficult times they were living in. He suggested they seek solace from and resilience in the “Aligarian sense of humour” and wit and poetry and literature. He devotes a long chapter in his book on his life in AMU,

“The Imli Tree”; the tree is supposed to be a symbol of faithfulness and forbearance, in the Budhist tradition. When I spoke of this to him, Muzaffar feigned ignorance and evaded my query as to why did he refer to Imli (tamarind) tree for the sweet [and sour?] memories of his AMU life. His plan to make a film on the trauma of pre-Partition Aligarh remains unfulfilled. In Aligarh, he identifies, Asghar Wajahat to be his closest friend. Referring to a line of Majaz’s poem, the AMU’s anthem (taraana), he complains, there is “too much of barrenness for the clouds [abr] that rise from Aliagrh to irrigate the parched world”. Throughout his memoir, he comes out as a brilliant translator of both prose and poetry of Persian and Urdu into English; just as he has organised the autobiography in well-integrated, logically interconnected chapters, having creative profiles of many characters of his life.

The initial chapters of his memoir talk about his ancestry. He quotes from an unpublished PhD dissertation of his father submitted to the Lucknow University. He claims to belong to the Chauras of Gujarat, who claimed their descent from the Lord Rama of Ayodhya, the name, “signified that no human blood would be shed on its soil, no war would be fought on its ground”.

His father has been a strong influence on him, who “lived his life as a humanist, a life true to his country and its ideals of harmony, opposing anything that divided man”. Enamoured with the Brahmo Samaj, his father wrote on similarities between Advaita and Sufism, to find commonalities in faiths. His Abba, “specially gifted in the art of storytelling” told him stories at mealtimes; “stories and more stories made up the lessons of life”. Tilism-e-Hoshruba’s and Dastan-e-Amir Hamza’s characters such as magician Afrasiyab, the intelligent trickster Amr Ayyar were the usual stuff, in the Kotwara world of “simple innocence”, a holy town of Gola Gokaran Nath, with its Shiv Temple, built by his ancestors, which also had once the largest sugar mill in Asia, “a melting pot of ideas, of the coming together of beauty and humanity; seeing and living Sufism on the soil of Awadh”.

A fierce nationalist, vehemently opposed to and betrayed by the Muslim League; his father’s uncle having assured his father help in the elections, called him to a mosque on a Friday prayer, and told the assembled devotees that voting for him, against the League, would throw all them straight into hell. Muzaffar’s father was shocked and predictably lost the election in 1946. In return, after partition, his father would keep reminding, “a raven may not take a single bone from my body across to Pakistan”. His Abba loved someone in the kinship who “was often asked why he eulogized India, a country where cows are worshipped. He would retort that in Pakistan, donkeys are worshipped”.

For the students of modern Indian history to get such deep, unusual insights about the hazards of the politics of Khilafat and Partition, Muzaffar Ali’s memoir, and his father’s portrait into it, offers great wisdom.

Next to Intizar Husain’s Urdu biography of Hakim Ajmal Khan, Ajmal-e-Azam (1999), Muzaffar Ali’s memoir is perhaps one of the rarest pieces of writing to have some candid and forthright details about the futile and hazardous politics of Khilafat. This Pan-Islamist mobilisation gets a subtle disapproval from Muzaffar Ali. The Muslim leadership of India had misled the Muslim masses mobilising them for restoration of a corrupt and degenerated institution far away in Turkey. The Indian leadership, too, kept the masses in dark as to how much unpopular had it become. The dethroned fugitive Ottoman Caliph had her princesses married off to the Indian princes (aristocrats) in Awadh and Hyderabad. One such prince was Muzaffar’s father, educated in Britain. The princess however soon deserted his father, ran away to Paris with the baby-girl, Kaniz, who was recovered with great difficulties, in 1962. His father knew, by the 1930s, “that the Muslim League would result in an ugly India”. He remarks, “Undivided India was torn politically between its vast Muslim population and its struggle for independence. The British played a major role in shaping minds and loyalties. Fifteen million Indians fought a war that was not theirs”. In the World Wars the British used Indian armies, “one million of Indian soldiers died. The leadership working on fanning anti-British sentiments used this emotionally”.

Muzaffar Ali claims his father, as elected member of the legislature, helped “minimizing the impact of migration in 1947 leading to the rehabilitation of the Sikh population in large numbers in the Terai region”.

Muzaffar is also fascinated with “fearless (Be-Khauf) and self-reliant (Khud-Aitamaad) women, such as his father’s sister. Though, her migration to Pakistan had shattered his father; another blow to his father came in February 1964, when Muzaffar’s mother passed away. So was Muzaffar too; his brother and mother both were suffering from incurable ailments: “But my days in Aligarh had a deep undercurrent of turmoil… I would go back to Aligarh with more pain than I could rise above”. His project of making a film on the fearless, self-reliant Mughal Empress Nur Jahan however remains unfulfilled, as yet.

At the age of 22, in 1966, he went to Calcutta passing through, “poverty-stricken, jobless” regions of eastern India. “Calcutta was a city fluent in the language of money”, “a weapon of subjugation, of tyranny and exploitation”. It “opened a world I could not have imagined in the wildest of dreams”. He met there his extended kinship such as the novelist Attia Hossein, who “appeared as a character in Gone with the Wind but could represent the modern Lucknow of the 1930s”. He was introduced to the “English theatre world of Calcutta”, the film maker Mrinal Sen, and of course Satyajit Ray, with whom he worked. In Calcutta Muzaffar got his first wife Geeti Sen, an art historian, a PhD on the paintings of Akbarnama from Philadelphia.

Having discussed each of his great films in separate, exclusive chapters, the pursuit of film-making revealed to him “the ugliness of film politics; camps and groups, rumours and espionage”.

Describing his indulgence in electoral politics, he found out that the world was increasingly “becoming crueler”; he “could see the ugliness of politics, smell the stench of power”. While going for door-to-door campaign, he found that it was a “mug’s game” at his level, whereas at higher level it was “game for mugs”; it was “all about ego”; “simplicity was lost in the politics of caste and communalism”; “demented leadership misleading the simple minds”. His description of Amar Singh kind of character in politics is extremely perceptive; where “strange characters show up, holding our future to ransom”.

About Lucknow of the 1990s:

“[He] discovered that an invisible layer of the RSS had taken over the cultural fabric of Lucknow and the entire Awadh region, a reaction to the Muslim League. The erstwhile Muslim taluqdars had shattered the Ganga-Jamuni myth by affiliating with the Muslim League around the time of Partition. They were secular to the core but stood by the communal forces of the League”…. “There was a tacit understanding with Amar Singh that I had to lose”. “While we dreamt of a future for Awadh that evolved out of its heritage of interdependence between craft and culture, the venom of communalism was spreading fast [and furious]”.

Muzaffar Ali turned, again, to art and poetry. An art commentator identified Muzaffar, the painter, as an Abstract Expressionist. For the answer to the problems of fratricide in India, Muzaffar turns towards the poets, Rumi (man to lead humanity into the twenty first century) and Amir Khusrau, the two “will forever continue to water my art, and make miracles happen to soften hearts and refresh human souls. We salute their invisible sawaar (rider) on the horse [rakhsh] of ishq [love]”.

In the lap of the two sufi poets, he wraps up his memoir, Zikr (a Sufi terminology, with many layers of meanings): This reminds us of Ghalib’s couplet:

rau meñ hai raḳhsh-e-umr kahāñ dekhiye thame

ne haath baag par hai na pā hai rikāb meñ

May Muzaffar Ali live longer and healthier to give us a sequel of his memoir as well as to give us the films he has been contemplating to make!

(The author is a Professor of History, Aligarh Muslim University)

Related:

The assault on the National Film Archives and Films Division is an assault on Constitution

Bollywood’s Conscience Speak: Celebs against anti- CAA violence at Jamia, AMU