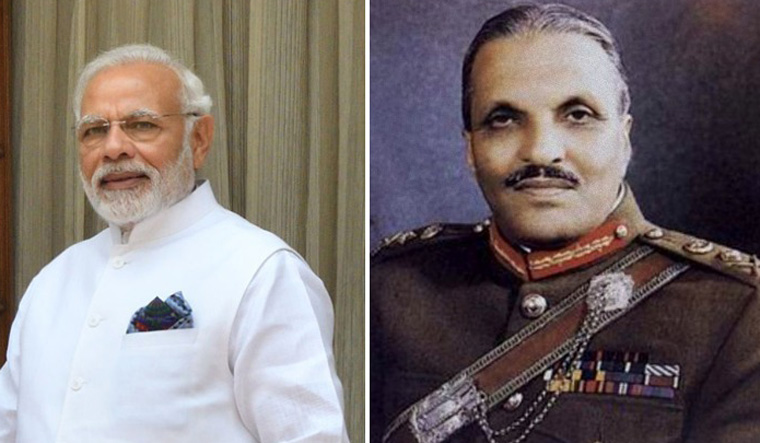

“Excavation of the Zia period [in Pakistan] is of direct relevance to those who wish to mobilise and articulate a politics of resistance…” write Virinder Kalra & Waqas Butt, on resistance poetry in repressive regime of Gen. Zia (1977-88). This essay (Modern Asian Studies, 2019) is a telling parody for what is currently afoot in NaMo’s India.

I feel tempted to share certain excerpts from this renowned essay, with slight adaptations/paraphrasing, for, knowing the brutal Oppression and Resistance that emerged to fight it out:

General Zia polarised Pakistani society on many axes, one of which was that of ethnicity. A cleavage between the two main populous areas of the country was created. The advent of General Zia’s period of military rule, in 1977, signals the demise of [oppositional] politics in Pakistan, where the possibility of social and political change through civil processes glimmered in the public consciousness, [for some time]. The institutional changes and social processes instigated by Zia, are described, in the essay, as ‘evil’.

The main ‘objectives of Zia’s martial law’ were:

1. To crush the movement of progressive people especially the left wing leadership.

2. To reduce the importance of democratic and popular political parties in national politics.

3. To patronise right-wing political parties and student organisations to fill the political vacuum among the masses and to use them against left-wing and popular forces.

4. To promote Islamic ideology and an Islamic system to obtain the above-mentioned objectives, further providing justification to prolonging martial law.

*”Women and [ethnic, sectarian] minorities thus became the main targets for an Islamic-‘ally’ justified, but, in practice, traditional use of coercive power. The social cleavage along the lines of gender, ethnicity, biradari, and religion became instruments by which “Zia maintained power, funded by the USA, through the Afghanistan conflict and with the support of the feudal and business elite”.

The ethnic and sectarian divisions that were part of Gen Zia’s (1977-88) political strategies in Pakistan were resisted not only through street protests and political opposition, but also in the realm of culture. In particular, poetry was a vehicle through which to express discontent as well as to mobilize the population. [When the communal-military regime] had quelled formal opposition in the media and civil society, and political figures fell into balance, poetry sustained the beacon of hope and resistance. “Students and peasants who were subjected to imprisonment and torture”, also engaged in resistance literature. These resistances that emerged were from the non-elite, marginalized sections and away from major cities and outside formal literary circles. They were less likely to be co-opted by the state. It was they who became the frontline crusaders.

The oppressive regime therefore became menacingly intrusive into literary-cultural organisations and student politics. The small groups of left-wing parties were closely monitored and their ideological differences exploited to prevent collective assertion against the regime. This targeting of the left was less to do with their numerical power, but an assertion of the ideological outlook of the regime, in which Islam was wielded with cynical force against the ‘anti-Allah Marxists’.

The organised state indulged in “excesses in the field of human rights (which) were well documented”.

Zia’s theological reforms created conditions of ‘mob rule’. Summative justice at the local level reflected the lack of rule of law as a principle. Religion and sectarian majoritarianism were invoked to suppress dissent and to dispense with democracy. Zia was more successful in the breaking of student movements and general opposition. Three “journalists were flogged” (in 1978) who were critical of the regime. This was on a ‘judicial pronouncement’.

“Thus, judiciary had fallen to (diktats of)the regime”.

Once the Zia regime had [crushed the] students in 1984, the next level of resistance to be tackled was that of the teachers. Rather than sacking teachers, which could have meant confrontation with [their associations], two strategies were adopted: The first was the takeover of teachers’ associations by the Jamaat-e-Islami—a right-wing religious party supporting the regime. The second strategy was to post ‘troublesome’ teachers to remote areas. [This is how the Sahiwal College was destroyed].

The vibrant political atmosphere centred at the Government College Sahiwal in the early to mid-1970s was in for a rude shock with the introduction of martial law. This took a number of forms. First, the college was closed for the best part of a year while the military established itself. Alongside this, venues such as Café De Rose, where students, intellectuals, and professors would gather for more informal and political/literary discussions, closed as bans on public gatherings took force.

Indeed, it was these spaces that also became the hunting ground for state agencies looking to clamp down on left-wing and anti-martial-law activists. Students were arrested and professors posted to remote areas as a way of disrupting political activism.

Historian Mubarak Ali (2012), writes, ‘They realised that they would lose the struggle against the state and its institutions, but in spite of this fact, the movements of resistance continued to oppose suppression and to sustain the hopes of the people that change was possible. In this way, their defeat was their victory’.

Resistance to the regime emerged in 1979-80 with the agitation by the Shia minorities, against a *discriminatory legislation*. In July 1980, this minority’s agitations forced the regime to modify it.

Thus, protests forced the regime to relent, and it gained ground, then on.

Poetry of poet-activists of rural towns articulated the concerns of those opposed to the Zia regime in the languages of the masses, but in a form that translated spontaneous resistance to an articulate opposition.

‘If I Speak, They Will Kill Me, to Remain Silent Is to Die’: Poetry of resistance in General Zia’s Pakistan (1977–88):

The ethnic and sectarian divisions that were part of General Zia’s (1977–88) political strategies in Pakistan were resisted not only through street protest and political opposition, but also in the realm of culture. In particular, poetry was a vehicle through which to express discontent as well as to mobilize the population. By offering an analysis of a number of poems and the biographies of the political poets who wrote them, this article offers another perspective on the question of resistance in this period of Pakistan’s history. Whilst the outcome of the policy of ethnic division was to divide the struggle against General Zia into a broad anti-Punjab front, this article highlights how it was class division and the securing of elite consent that were the major achievements of the Zia regime. In contrast to previous research, we highlight how resistance came from all groups in Pakistan as reflected in the poetry and literature of the time.

(Professor Mohammad Sajjad is with Centre of Advanced Study in History, Aligarh Muslim University, and is author of Muslim Politics in Bihar: Changing Contours (Routledge 2014/2018 reprint). He tweets @sajjadhist)