In the past two years, the Indian government has introduced two major amendments to the existing environmental laws, namely the Biodiversity Amendment Act, 2023, and the Water Conservation Act, 2024. These amendments have been met with mixed reactions from various stakeholders, including environmentalists, civil society organizations, and the public. While some have welcomed the amendments as a pragmatic and flexible approach to balance the needs of development and conservation, others have criticized them as a dilution of the environmental standards and a threat to the ecological integrity of the country. In this article, we will examine the main features and implications of these amendments and evaluate whether they are a step towards leniency or a leap into laxity in the environmental governance of India.

What is Biodiversity and why is it important for any one of us to conserve?

Biodiversity, short for “biological diversity,” encompasses the variety of life on Earth, from genes to ecosystems, and the processes that sustain life. It includes all living organisms, from humans to microbes. Biodiversity supports essential needs like food, water, medicine, and shelter. For example, pollinators like bees are crucial for crops; their decline due to pesticides and habitat loss threatens food supply.

Diverse ecosystems are more resilient to stressors like drought or disease. For instance, the dominance of the Cavendish banana, vulnerable to a particular fungus, highlights the risks of low crop diversity to food security. Degradation of nature increases disease outbreaks, as 70% of emerging viral diseases originate from animals. Increased human-wildlife interactions raise the risk of disease transmission.[1] Over half of global GDP depends on nature, with more than a billion people relying on forests for their livelihoods.

Conserving biodiversity is crucial for maintaining ecosystem balance, ensuring a healthy planet for future generations, and preserving essential ecosystem services.[2]

Why was CBD enacted and how does it impact conservation of biodiversity?

Convention on Biological Diversity-a first of its kind agreement on Biodiversity Conservation- was signed at the 1992 Rio Earth Summit with the aim of promoting sustainable development. The convention recognises that biological diversity is about more than plants, animals or microorganisms and it is about people and their need for food security, medicines, fresh air, water, shelter, and healthy environment in which they can live. It has three main principles[3]:

- Conservation of Biological Diversity

- Sustainable use of its Components

- Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits arising from Genetic Resources

There are 2 protocols- that were later adopted-the Cartagena Protocol (2003) dealt with movement of living modified organisms resulting in modern biotechnology from one country to another; Nagoya Protocol (2014) dealt with Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilisation.

It is to effectuate this Convention that Vajpayee led NDA government brought the Biological Diversity Act, 2002.[4]

What were the main features of the Biological Diversity Act, 2002?

The Biological Diversity Act, 2002, was enacted to implement the Convention on Biological Diversity, to which India is a signatory, and to regulate the access and benefit-sharing of the biological resources and associated traditional knowledge of the country. The Act established three-tiered institutional mechanisms, namely the National Biodiversity Authority (NBA), the State Biodiversity Boards (SBBs), and the Biodiversity Management Committees (BMCs), to oversee the implementation of the Act. The Act also required prior approval from the NBA for any access, research, commercial utilization, or transfer of results of research on any biological resource or associated knowledge by any person, including Indians, non-residents, and corporate entities.

Restrictions on transfer of resources or knowledge to foreign nations:

For instance, if a company wants to use a plant species found in India for developing a new drug, it will need to seek permission from these bodies and share the benefits with the country. This helps protect India’s rich biodiversity and the rights of local communities that have preserved this knowledge for generations.[5]

Even Indian scientists would require approval of the National Biodiversity Authority for transferring the results of research to foreign nationals/ foreign organisations.[6]

Restrictions on Indian Nationals for Commercialisation

Section 7 of the Act-before the 2023 amendment- stated that any citizen should obtain any biological resource for commercial utilisation, or biodiversity and bio utilisation for commercial utilisation only after giving prior intimation to the State Biodiversity Board concerned. Exemptions were given to local people and the community of the area, including growers and cultivators of biodiversity, and Vaids and Hakims who have been practicing indigenous medicine.

Regulations regarding grant of Intellectual Property Rights

Section 6 of the original act before the amendment mandated that no person shall apply for any intellectual property right in or outside India, for any invention based on a biological resource from India without obtaining prior approval of the NBA-before making such application for the grant of IPR. It also empowered the NBA to impose benefit sharing fee or royalty or both or impose such conditions of sharing of financial benefits arising out of the commercial utilisation of such IP rights while granting the approval.

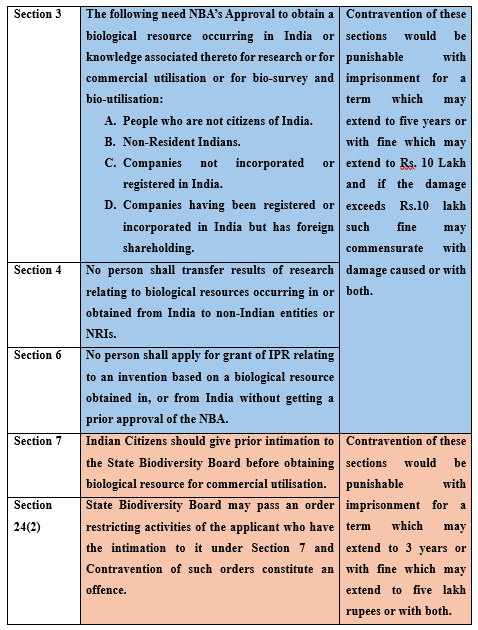

Punishments:

What were the features that were changed by BD Amendment, 2023?

Restrictions on Indian nationals for commercialisation:

The change brought in by the amendment is that the exception of not requiring prior intimation to the state biodiversity board for accessing biological resources and its associated knowledge for commercial utilization was extended to codified traditional knowledge, cultivated medicinal plans and registered AYUSH practitioners who have been practicing indigenous medicines including Indian systems of medicine as profession for sustenance and livelihood.

Essentially, the amendment made an exception for AYUSH practitioners apart from the previously exempted categories of hakims and Vaids, as far as person are concerned. At the same time, the amendment also made an exemption for the codified traditional knowledge or cultivated medicinal plants- meaning if one is accessing codified traditional knowledge or the cultivated medicinal plants- they do not have to give intimation to the SBB.

Regulations regarding grant of Intellectual Property Rights

A significant change from the original act as far as IPR is concerned is that foreign entities may apply for the approval of NBA before the grant of the Intellectual Property Right rather than the old procedure of obtaining approval before the application for IPR. This, according to the proponents of the change, will expedite the process of getting IPRs granted.

For Indian entities-they merely need to register with the NBA before grant of the IPR and if they have already obtained the IPR, they shall obtain the approval of NBA before commercialisation.

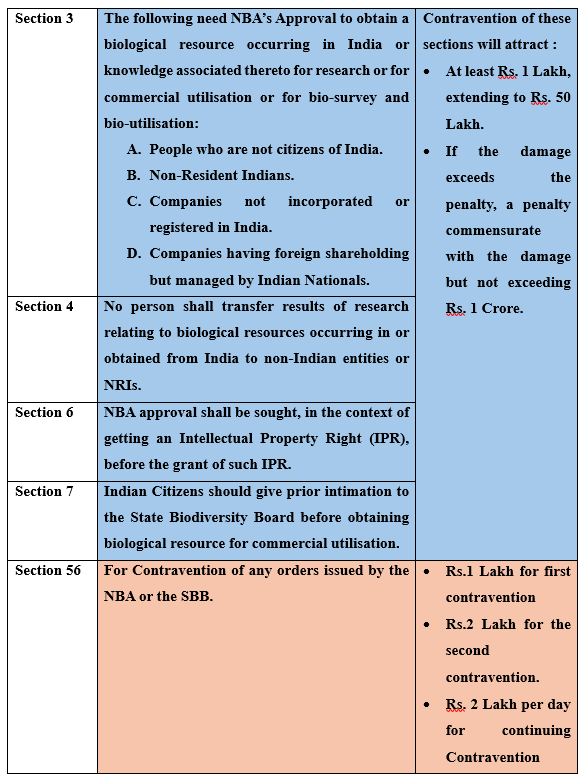

Punishments

The issues with the Biological Diversity Amendment Act, 2024.

Ambiguity with respect to AYUSH practitioners:

The Amended version of the Section 7-like the original act- of the Act has two components. Section 7(1) states that no person can access Biological Resources without giving prior intimation to the concerned State Biodiversity Board.

The second component-Section 7(2)-provides exceptions i.e., those who do not have to give a prior intimation to the SBB before accessing biological resource. According to the original act, only local people and communities of the area, including growers and cultivators of biodiversity, Vaids and Hakims-who have been practicing indigenous medicine were exempted. However, according to the amended act, registered AYUSH practitioners who have been practicing indigenous medicines including Indian systems of medicine as a profession for sustenance and livelihood are also exempted from intimating to the SBB.

Essentially, if an Ayurvedic Doctor -who practices Ayurveda for livelihood and sustenance-wants to access biological resource, she does not have to give prior intimation to the SBB.

Why should this matter? It matters because sustenance and livelihood are not defined under the act-meaning that the companies in the AYUSH industry could bypass the requirement to give intimation to the SBB by employing the AYUSH practitioners to access the biological resources.

While Vaids or Hakims could have been used for the same purpose, the fact that Indian companies have long contended that they do not have to seek prior approval from the SBBs according to the original act. In the case of Divya Pharmacy vs. Union of India-the Uttarakhand High Court noted that the Biodiversity Act, 2002 is a socially beneficial legislation and that it needs to be interpreted in line with the purpose for which it was enacted.[7] In this case, the court pronounced that Indian Companies need to seek approval from the SBBs and need to share a part of their revenue with the local communities that are responsible for conserving and protecting such resources. The judgement, authored by Justice Sudhanshu Dhulia, relied on the Nagoya protocol and the Convention on Biological Diversity and stated that the scheme of Fair and Equitable Benefit sharing cannot be looked through the narrow confines of the definition clause alone. The judgement said “that the FEBS concept has to be appreciated from the broad parameters of the scheme of the act, and the long history of movement for conservation together with our international commitments in the form of international treaties to which India is a signatory.”

The amendment does not mandate a mechanism for the prior consent of the local ad indigenous communities or a consultation while approving access to genetic resources and knowledge.

The bill when introduced in the Lok Sabha had facilitating fast-tracking of research, patent application process and bringing foreign investments in the chain of biological resources, including research without compromising national interest among the objects which the amendment seeks to achieve. However, the amendment presents more ambiguity on one of the three principles of the main act- the Principle of Fair Access and Benefit Sharing.

The Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Amendment Act, 2024

The Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Amendment Act, 2024, introduced significant changes to the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974. The Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974 was introduced in India with the aim to prevent and control water pollution and maintain the wholesomeness of water. This act was enacted after the adoption of the United Nations Environmental Conference held in Stockholm in 1972.

The Act confers powers to established bodies such as the Central Board and the State Board to control pollution of water bodies. While water is a state subject under the Constitution, the Centre can enact a legislation if 2 or more states’ legislatures pass a resolution to that effect and other states can adopt the centre enacted law. This 2024 amendment was enacted by Centre in pursuant to Rajasthan and Himachal Pradesh legislatures’ resolution.[8]

- Exemption of Certain Categories of Industries from getting the SPCB permissions via notification: The Amendment Act empowers the central government, in consultation with the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), to exempt certain categories of industrial plants from obtaining prior consent for establishment if they are likely to discharge sewage or other pollutants. This provision is aimed at simplifying regulatory procedures for specific industries, potentially boosting economic activities while ensuring environmental safeguards are in place.[9]

- The Amendment Act authorizes the central government to issue guidelines for the grant, refusal, or cancellation of consent granted by the State Pollution Control Boards (SPCBs). This is intended to standardize the governance of state boards, ensuring uniformity in the fight against water pollution across states. The State Pollution Control Boards are mandated to follow these guidelines.[10]

- The Amendment Act replaces several violations previously punishable under the 1974 Act with financial penalties ranging from Rs 10,000 to Rs 15 lakh. This approach is designed to deter non-compliance through economic disincentives rather than criminal prosecution, aiming to foster a more compliance-oriented business environment. The Amendment Act replaces provisions in the act for imprisonment from three months up to seven years with amended text specifying fines up to Rs 15 lakh and, under certain conditions, Rs 10,000 per day for violations.[11]

What are the issues with the Water (Amendment) Act, 2024?

The amendment encroaches upon the state’s power to allow which kinds of industries it can allow in its territory. Additionally, it takes the power from states to frame rules for issuing of certificates etc. – meaning the superimposing powers on giving permissions to categories of some industries and regulating all kinds of industries via the guidelines which the states are mandated to follow are allocated to the Centre.

While states other than Rajasthan and Himachal Pradesh will have to adopt this law for it to be applicable to them, the fact that a tendency to centralise and also decriminalise environmental offences while making laws that are supposed to protect environment- is alarming.

Decriminalisation and centralisation-part of a larger drive for ‘ease of doing businesses

Prior to this, the Jan Vishwas (Amendment of provisions) Act 2023 was enacted to decriminalise minor green offences related to air pollution, forest, and environment protection legislations.[12] The original Air Act stated that no person can establish or operate an industrial plant in an air pollution control area without the previous consent of the State Pollution Control Board.[13] The Jan Vishwas amended this provision and empowered the Centre to exempt certain categories of industries from seeking this consent from State Board.[14] Discharging air pollutant in excess of the standards laid down by the State Board according to the old Air Act attracted an imprisonment for a term between 18 months and 6 years with fine. Under the Jan Vishwas amendment, the provision for imprisonment has been removed and a fine has been imposed with the maximum extent of such fine being Rs. 15 Lakh.[15] Another feature of the penalty under the Jan Vishwas, especially with respect to release of pollutants is that for a continuing offence, an additional sum of only Rs. 10, 000 can be levied per day of such contravention.

It is not to say that everyone or any entity who emits a little excess of pollutants for the first time, even due to a mistake, should be thrown in jail or should be made to pay exorbitant sum of money to the state even when they cannot. However, the legislation seems to have not taken different cases into consideration. For example, an establishment which emits excess pollutants for a prolonged period of time-should be fined more heavily rather than Rs. 10,000 per day of contravention. Similarly, obstruction of anyone who is acting on the orders the board should attract more than fine, when there are such cases. Consider the following example under both the old and new acts. Consider Case 2 which does not warrant any stringent action under the Amended act and there is no reason for the government to propose this except for the growing need to make sure the India Inc. cannot be put in jail for violating environmental norms provided they pay fine.

| Old Air Act | Amended Air Act | |

| Case 1: A watchman of an industrial establishes stops the member authorised by the Board to come into the establishment because he does not have the communication from his employer to allow the member. The Watchman cannot read | Imprisonment

OR

Fine extending to Rs. 10,000 OR Both | Fine of not less than Rs. 10, 000 extending to Rs. 15,00,000 |

| Case 2: A group of people actively stop the member authorised by the board to visit the establishments on the instruction of the employer so that by the time a board member visit the establishment, a pollution causing error can be rectified.

| Imprisonment

OR

Fine extending to Rs. 10,000 OR Both | Fine of not less than Rs. 10, 000 extending to Rs. 15,00,000 |

Conclusion

India is at crossroads when it comes to enacting legislation as the climate change crisis looms near. The changes in the legislations discussed above indicate that the country is taking a step towards using its resources and legal system to give a sort of impunity for those who pollute rather than making sure the industry is green by design. The tendency to centralise systems that were decentralised does not have a solid reasoning. India could go this route and find itself in a place where damage cannot be reversed for 1.5 billion people or it can pause, take a re-look over why it should de-criminalise and centralise environmental decision making, thus forcing revisions like graded punishments, consultation with the State Pollution Control Board or the State Biodiversity Boards while exempting industries and granting approvals. This way, reforms can be achieved, and laxity can be avoided.

(The author is part of the CJP’s Legal Research Team)

[1] Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. (2015). First Estimate of Total Viruses in Mammals. [online] Available at: https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/research/center-infection-and-immunity/first-estimate-total-viruses-mammals [Accessed 24 Jun. 2024].

[2] World Economic Forum. (2024). Half of World’s GDP Moderately or Highly Dependent on Nature, Says New Report. [online] Available at: https://www.weforum.org/press/2020/01/half-of-world-s-gdp-moderately-or-highly-dependent-on-nature-says-new-report/ [Accessed 24 Jun. 2024].

[3] Cbd.int. (2024). Principles. [online] Available at: https://www.cbd.int/ecosystem/principles.shtml [Accessed 24 Jun. 2024].

[4] Act 18 of 2003, https://www.indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/2046?view_type=browse

[5] Section 3, The Biological Diversity Act, 2002.

[6] Section 4, The Biological Diversity Act, 2002.

[7] Para 42, Writ Petition (M/S) No. 3437 of 2016, Uttarakhand High Court.

[8] Kumar, N. (2024). Water Act 2024: HP, Rajasthan and UTs first to decriminalise small offences. [online] @bsindia. Available at: https://www.business-standard.com/india-news/water-act-2024-hp-rajasthan-and-uts-first-to-decriminalise-small-offences-124021901131_1.html [Accessed 24 Jun. 2024].

[9] Section 25(1), Water Act, 1974

[10] Section 27, Water Act, 1974

[11] Section 41, Water Act, 1974

[12] THE JAN VISHWAS (AMENDMENT OF PROVISIONS) ACT, 2023 NO. 18 OF 2023

[13] Section 21, Air Act, 1981

[15] Section 37, Air Act, 1981

Related:

In North Gujarat’s Granite-Rich Idar, Locals Fearful About Aravalli Mountains’ Future

India’s Telecommunications Act notified, ushers in “modernisation”with privacy concerns