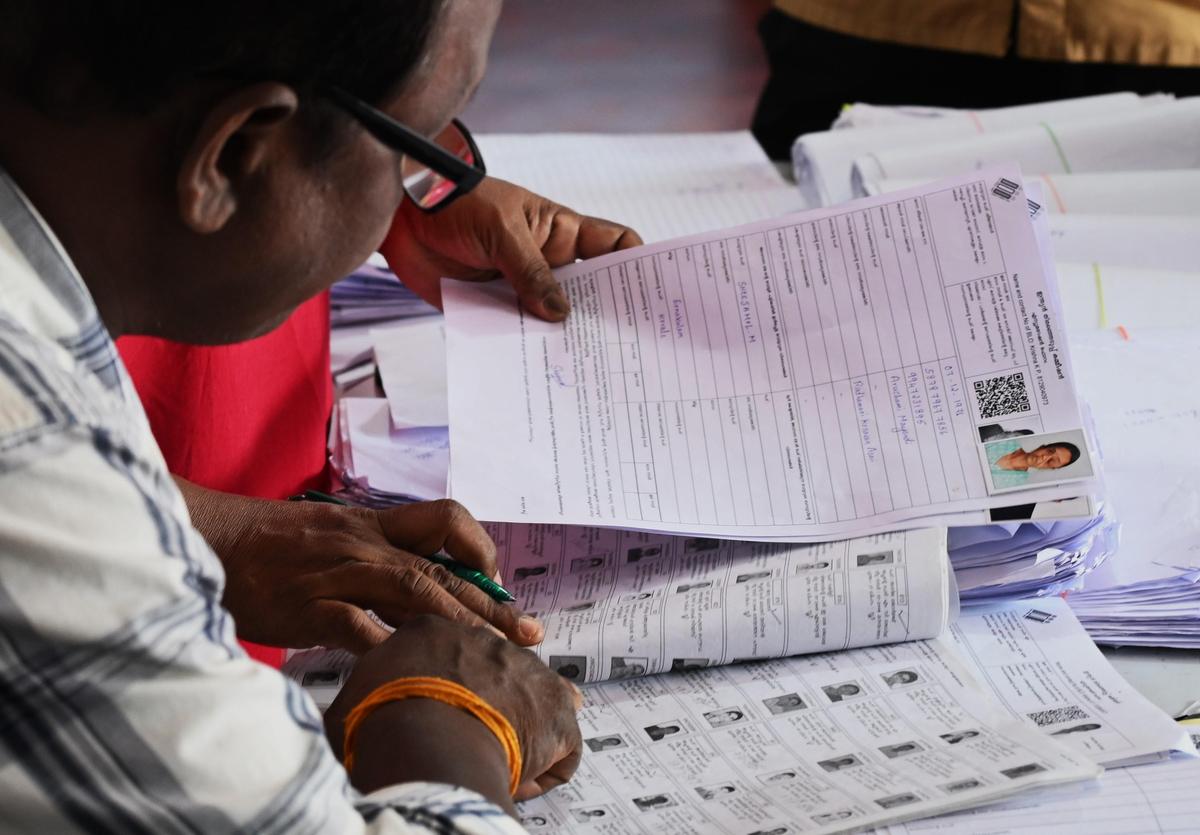

The Election Commission’s Special Intensive Revision (SIR), launched on November 4, 2025, moved rapidly through digitised enumeration forms and, according to the latest trends released during the process, identified around 50 lakh names in West Bengal as potentially eligible for exclusion from the electoral rolls. That provisional figure rose from a little over 46 lakh in the space of 24 hours, a pace officials described as a product of ongoing digitisation and categorisation of records.

The bulk of entries flagged so far fall into the categories that commonly prompt removal of deceased voters, those who have shifted addresses, untraceable names and duplicates.

The state’s electoral roll, as last certified on October 27, 2025, lists 7,66,37,529 registered voters. In proportion, the provisional 50-lakh figure represents a significant chunk of the electorate. Election officials and the Chief Electoral Officer’s office have stressed repeatedly that this is a provisional outcome of the digitisation exercise and must be understood in the administrative sequence that follows publication of the draft list, notices, hearings and disposal of claims and objections, and finally the ECI’s checks and permission for the final roll.

The draft list was scheduled for publication on December 16, 2025, with hearings and verification to follow before any name is finally deleted.

According to The News Minute, the officials working at the CEO’s office provided a breakdown of the roughly 50-lakh provisional cases: more than 23 lakh were classified as “deceased,” over 18 lakh as “shifted,” and more than 7 lakh as “untraceable,” with the remaining entries attributed to duplicates or other removal reasons. These categories mirror the normal administrative reasons that electoral rolls are pruned; however, the speed and scale of the flags — not just the categories themselves — have alarmed voters, civil society groups and political parties alike.

The final numbers will depend on hearings and verifications scheduled between mid-December and early February 2026.

How SIR became a public crisis

Petitioners challenging the SIR in the Supreme Court have argued on December 2 that the Special Intensive Revision is illegal and unconstitutional, claiming that the scale, timing and manner of its implementation violate established electoral norms. Despite the pendency of these challenges, voter-list revision remains, on its face, a routine democratic duty that both the State and the Election Commission of India are obligated to maintain accurate rolls so that eligible voters are neither omitted nor counted more than once.

Even so, aspects of the present exercise — its pace, concentrated timelines, the extensive door-to-door verifications carried out by Booth Level Officers (BLOs), and the near-real-time visibility of digitisation flags — unfolded in an environment of heightened public attention, leading to widespread anxiety among sections of the population. Social media circulation, intense political scrutiny and fragmented information channels further contributed to confusion about what provisional flags meant, particularly among vulnerable citizens.

In several districts, police and administrative logs recorded citizens who said they feared losing their names or being confronted with legal consequences because of missing paperwork. Interviews collected by reporters from families of victims described panic, confusion and, in some cases, pre-existing vulnerability — old age, lack of regular identity documents, migratory labour status or poor literacy — as the factors that turned an administrative notice into a cause of intense personal distress. The pattern of panic is not unique to this revision: previous national episodes where large administrative drives intersected with inadequate public outreach have produced similar outcomes. What made the present wave distinct was the speed with which thousands of provisional deletions became visible and the proliferation of alarming claims — anecdotal and political — across platforms, The News Minute reported

Field staff reported pressure, and the death of a few BLOs earlier in the exercise crystallised wider concerns. Employee associations, local administrators and civil society groups told reporters that the compressed timeframes required an exceptional workload from BLOs, who must complete verifications under deadlines, often with server or app issues, poor transport or unclear instructions. The tragic deaths reported during this period sparked urgent questions about whether adequate staffing, mental-health support and realistic timeframes accompanied a process of such scale.

#WATCH | Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala | BLOs across the state boycotted work in protest over the suicide of a BLO in Kannur. They marched to the office of the Chief Electoral Officer

In other districts, protests were held at the District Collectorates. The protest was jointly… pic.twitter.com/i7vhS7VEsc— ANI (@ANI) November 17, 2025

The tally of deaths and the state’s response

In the last weeks of the SIR exercise, the Trinamool Congress (TMC) compiled and presented lists of deaths they allege were linked to SIR-induced panic. The TMC delegation took such lists to the Election Commission and made repeated public claims that dozens of people, including BLOs and ordinary citizens, had died as a direct or indirect result of the SIR exercise. The party’s public figures described the deaths as a humanitarian crisis and a political failure of the SIR implementation. The TMC tabled “40” or “39” as the number of deaths in various submissions and press interactions, as the Times of India reported

On December 2, 2025, Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee announced a Rs. 2 lakh ex gratia payment for the families of 39 people she said had died due to “SIR-panic,” and Rs. 1 lakh for persons whose condition worsened during the verification exercise but who survived. The announcement was presented by the state as a humanitarian step to assuage grief and to remind citizens that the SIR process is not punitive in itself. The CM and state officials insisted the measure was necessary given the scale of distress and to underline the government’s role in supporting affected families.

For years, Delhi’s Bangla-Birodhi cabal has sat like vultures on Bengal’s rightful dues worth ₹2 lakh crore. And today, the same BJP that weaponised the Election Commission to ram SIR down Bengal’s throat is suddenly pretending to care about BLOs’ honorarium.

If the Centre had… pic.twitter.com/JaAJvMGKq0

— All India Trinamool Congress (@AITCofficial) December 1, 2025

The TMC also submitted lists to the Election Commission during a delegation meeting in New Delhi where party leaders voiced sharp criticism of the ECI and its conduct of SIR in West Bengal. The party accused the ECI of being insensitive to the emotional and social consequences of the drive, citing the deaths and hospitalisations reported from various districts. The TMC’s demonstrations and delegations intensified public and media focus on the human consequences of the revision exercise.

Sharing herewith my today’s letter to the Chief Election Commissioner, articulating my serious concerns in respect of two latest and disturbing developments. pic.twitter.com/JhkFkF6RWs

— Mamata Banerjee (@MamataOfficial) November 24, 2025

The ECI, meanwhile, has responded to the allegations in court and in public statements. According to The Hindu, in affidavits and hearings before the Supreme Court, the Commission described claims of mass disenfranchisement as “highly exaggerated” and maintained that the SIR is a constitutionally mandated and transparent administrative exercise intended to maintain accurate electoral rolls. The ECI also warned political parties against intimidating BLOs and stressed that any names flagged during digitisation will get due process in the notice, hearing and objection windows before final deletion.

These institutional exchanges — TMC’s claims and ECI’s rebuttals — unfolded in parallel to the state government’s relief announcements.

What the ECI says and what courts are hearing

The ECI’s defence of SIR in the Supreme Court highlighted that digitisation trends alone do not determine final deletions and that the statutory safeguards of notice, hearing and disposal of objections must play out. In written affidavits, the Commission argued that allegations of systematic disenfranchisement were factually unfounded and politically motivated, pointing to the processual safeguards embedded in electoral law. The Commission’s public posture included cautionary notices to political actors to avoid intimidation of field officers and to allow BLOs to complete verifications unhindered.

At the same time, political delegations from West Bengal argued before the ECI and in the media that the pace, the timing and the perceived motives behind SIR risked alienating communities and that the ECI needed to exercise greater sensitivity. These tensions — legal, administrative and political — set the terms for the weeks leading up to and following the publication of the draft roll on December 16, 2025.

Mamata’s public outreach: ‘May I Help You’ camps and rallies

In response to the surge of panic, and framed as a rights-protection measure, Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee announced a large-scale outreach plan. Beginning on December 12, the state government will set up “May I Help You” camps across every block in West Bengal.

The stated objective of these camps is to assist people whose names are flagged in the draft roll, help them assemble or correct documentation, guide them through the claims and objections process, and ensure that no genuine voter is removed simply for lack of paperwork. The camps are also meant to offer a visible and immediate reassurance to citizens that the state will actively support them during hearings and verifications.

Mamata has deployed these announcements in public rallies and district visits where she has framed the SIR process as being politically charged and pushed by the Centre.

‘কোটিবার বাংলা ভাষায় কথা বলব!’ — বিজেপিকে চ্যালেঞ্জ জননেত্রী মমতা বন্দ্যোপাধ্যায়ের।#MamataBanerjee pic.twitter.com/xhYemx9K5K

— Banglar Gorbo Mamata (@BanglarGorboMB) December 3, 2025

In rallies, she has warned against “weaponising” the revision and has called on party workers and local officials to assist citizens in the help camps. The CM’s public speeches have combined administrative directives (the establishment and staffing of camps) with political claims about motives and effects, aiming to both reassure vulnerable residents and mobilise political solidarity ahead of the assembly elections scheduled for 2026.

Mamata’s own account on X (formerly Twitter) amplified the compensation announcement and the help-camp plan: her verified handle posted the government’s decisions and appealed for calm, signposting the administrative steps being taken in the coming days. Official state and party handle also circulated schedules for district-level visits, helpline numbers and details of local camp venues as these were finalised.

It is sad and unfortunate that we have lost 29 precious lives due to disruption in health services because of long drawn cease work by junior doctors.

In order to extend a helping hand to the bereaved families, State Government announces a token financial relief of Rs. 2 lakh…

— Mamata Banerjee (@MamataOfficial) September 13, 2024

Helplines, camps and the practicalities of the relief plan

State officials described the “May I Help You” camps as a three-part intervention as immediate assistance to citizens flagged in digitisation (document checks and form help); facilitating representation at ERO hearings by informing registered claimants about hearing dates and rights; and providing limited financial relief where deaths or serious health deterioration could be credibly linked to SIR-induced distress.

West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee has firmly addressed feⱥrs around the ongoing SIR (Special Identification and Registration) exercise, assuring the public that “no one will go to Bangladesh.” She announced “May I Help You” camps beginning December 12 across the state,… pic.twitter.com/LQWhKNBleI

— The Logical Indian (@LogicalIndians) December 4, 2025

The camps are to be staffed by government clerical personnel, local health-and-welfare officers and — in places — TMC volunteers, according to state releases. The efficacy of these camps will depend heavily on local logistics: transport to block headquarters, staffing levels, coordination with electoral officers and clear public communication about timelines and required documents.

The state said the payments for bereaved families — the Rs. 2 lakh ex gratia — would be expedited and administered through district disaster relief desks or equivalent welfare channels. For survivors who suffered severe illness during the SIR period, officials said a Rs.1 lakh assistance would be made available upon verification of medical records and circumstances. The practical implementation — how quickly families will receive money, whether the assistance will be disbursed as one-time grants or routed through existing welfare programmes — will be closely watched by the media and rights groups in the weeks ahead, as the Times of India reported

Moreover, the SIR exercise in West Bengal encapsulates a difficult administrative paradox that electoral rolls must be accurate to preserve democratic fairness, yet the processes that produce that accuracy must be implemented in ways that avoid causing social harm. The provisional flagging of nearly 50 lakh names created a public crisis because the mechanical outcome of digitisation met a social reality where millions of citizens — some undocumented, some mobile, some vulnerable — lacked reassurance about what a provisional flag meant for their legal rights.

The West Bengal government’s compensation for families and the creation of block-level “May I Help You” camps are immediate, targeted responses to the humanitarian fallout; the ECI’s court submissions and processual guarantees are the institutional reassurance that legal safeguards remain in place. Whether these parallel interventions will restore confidence will depend on the quality of on-ground implementation: transparent hearings, accessible help desks, rapid disbursement of relief where appropriate, and a clear, plain-language public information campaign explaining rights and remedies.

Related:

Pregnant woman deported despite parents on 2002 SIR rolls, another homemaker commits suicide