The dry reservoirs—despite a “normal” monsoon—of south Karnataka’s Cauvery basin illustrate India’s rainfall trends over 65 years: A drop in moderate monsoon rainfall and an increase in extreme events, such as deluges and dry spells, as IndiaSpend reported in April 2015.

A view of the Betwa river in Orchha, Madhya Pradesh. A new analysis of rainfall data reveals that monsoon shortages are growing in river basins with surplus water and falling in those with scarcities, raising questions about India’s Rs 11 lakh crore plan to transfer water from “surplus” to “deficit” basins.

Now, a new analysis of rainfall data reveals that monsoon shortages are growing in river basins with surplus water and falling in those with scarcities, raising questions about India’s Rs 11 lakh crore ($165 billion) plan to transfer water from “surplus” to “deficit” basins.

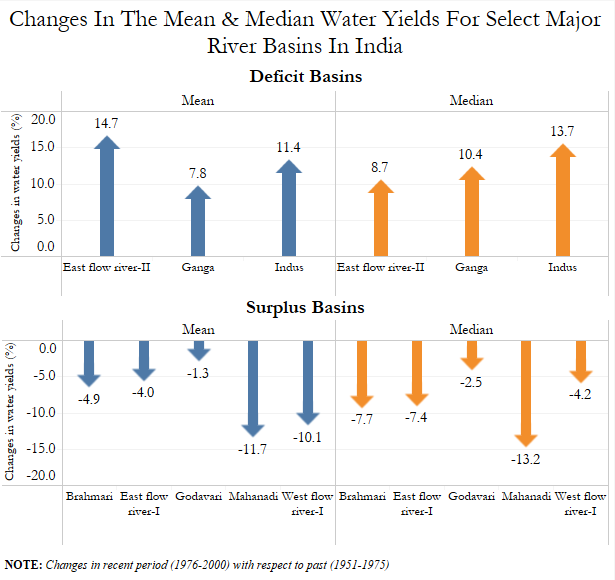

Water in surplus basins—such as the Mahanadi and other major west-flowing rivers in western India—fell more than 10% over a quarter-century (the period between 1951-1975 and 1976-2000) and increased by more than 10% in the Indus, the Ganga and some east-flowing rivers down south, according to this study in PLOS One, an open-access global journal.

Source: PLOS One

“Narrowing disparities in the water yield of Indian river basins call for an immediate reassessment of inter-basin water transfer plans,” Sachin S Gunthe, corresponding author of the study and associate professor, department of civil engineering, Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Madras, told IndiaSpend.

At 2001 prices, 30 inter-basin transfers—through a proposed network of canals, dams, aqueducts and pumping stations—were budgeted at Rs 560,000 crore ($124 billion at 2001 exchange rates). In April 2016, water resources minister Uma Bharati revised the estimate to Rs 11 lakh crore, almost double the estimate made 15 years ago—a sum equivalent to 44 times India’s agriculture budget or 1.6 times all government spending in 2015-16.

Peninsular Links

1. Mahanadi (Manibhada), Godavari Dowlaiswarm

2. Godavari (Inpampali) Krishna (Nagarjuna Sagar)

3. Godavari (Inchampali low dam-Krishna Nagarjuna sagar tail pond)

4. Godavari (Polavaram) Krishna-Vijaywara

5. Krishna-(Almati) Pehner

6. Krishna (Srisailam) Penner

7. Krishna Nagarjuna sagar (Pennar Somasaila)

8. Bensar (Somasaila) Cauveri Grand Ahicut

9. Cauveri (Katalai) Vaigai-Gundar

10. Ken-Betwa

11. Parwati-Lalisingoh-Chambal

12. Par- Tapi-Narmada

13. Damanganga-Pinjal

14. Bedti-Bharda

15. Netrabati-Hemavati

16. Pamba-Achankoyil- Vaipar

Himalayan Links

1. Kosi-Mechi

2. Kosi-Ghaghara

3. Gandak-Ganga

4. Ghaghara- Jamuna

5. Sharda- Jamuna

6. Jamuna-Rajasthan

7. Rajasthan-Sabarmati

8. Chunar-Sone-Barrage

9. Sone Dam-Souther tributaries of Ganga

10. Brahmputra-Ganga(MSTG)

11. Brahmputra-Ganga (GTF) (ALT)

12. Farakka-Sundarbans

13. Ganga-Damodar-Subernrekha

14. Subernrekha-Mahanadi

Source: Water Resources Department

The first river-linking project—meant to bring the waters of the Ken river 231 km from Daudhan in Madhya Pradesh to drought-ridden Bundelkhand in western Uttar Pradesh—was cleared in September 2016 amidst controversy, since it would mean submerging 100 sq km of central India’s Panna tiger reserve.

Despite the new evidence that changing monsoon patterns may require a review of the inter-basin water-transfer programme, a government spokesperson questioned the study’s interpretations, while India’s environment minister acknowledged to IndiaSpend that since there were “many conflicting opinions”, the Ken project would test the waters.

“Our preliminary analysis of the IIT faculty study suggests that while the data analysis may be correct, they have reached the wrong conclusion,” S Masood Husain, director general of the National Water Development Agency, told IndiaSpend.

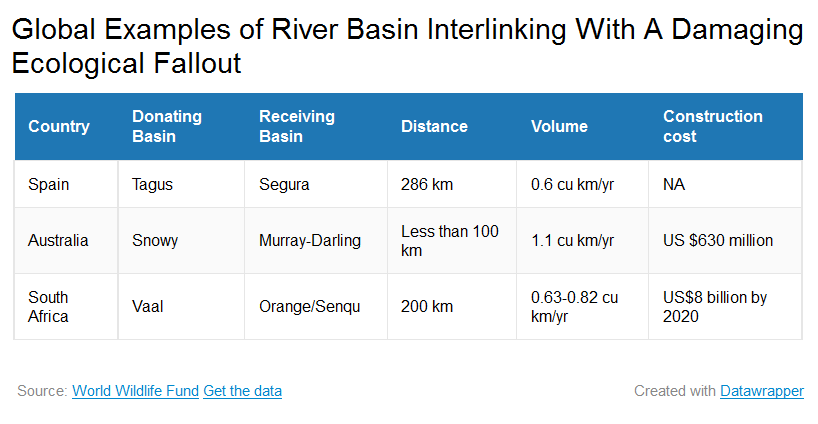

Independent experts advocated caution before going ahead with a multi-billion-dollar effort that has led to ecological upheavals in other countries, and in one instance partially reversed in Australia with dams being retrofitted. Globally, linking rivers is now a contentious issue.

Clearly, “there is a need to better understand the hydrology of basins and collate more evidence to establish whether a basin is surplus or deficit,” said Suresh Babu S V, director (rivers, wetlands and water policy) at the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) India, a global wildlife advocacy.

The controversy over river-linking begins with the financial costs.

With incomplete cost estimates, accurate cost-benefit analysis is difficult

The original $124 billion estimate of 30 inter-basin transfers excluded key expenses, such as the cost of dams, relief and rehabilitation and electricity need to pump water, according to this July 2016 report (co-written by former Planning Commission member Mihir Shah) on restructuring the Central Water Commission and the Central Ground Water Board.

Several cost estimates were missing.

Consider the Ken-Betwa link, which water resources minister Uma Bharti called a “model project”, which sets aside a third of its Rs 15,000 crore ($2.2 billion) budget for environmental management and rehabilitation. But estimates of the “ecosystem services”—including riverbed sand, winter fishing and ecotourism—that the river Ken provides, and may be affected when its waters are linked with the Betwa’s, find no mention in the project report, said experts.

For instance, sand worth Rs2,575 crore ($ 387 million) is extracted from the Ken riverbed near Banda, Bundelkhand’s easternmost district alone, according to this 2016 report of the ministry of environment, forest, and climate change and GIZ, a German agency working on sustainable development. Winter fishing at different sites is valued between Rs 3 lakh and Rs 17 lakh, and ecotourism across the 543–sq-km Panna Tiger Reserve—18%, or 100 sq km, will be lost to the project, as we said—Raneh falls and a crocodile sanctuary at Rs 7.69 crore.

“Changing the Ken’s course is likely to adversely impact these valuable ecosystem services, but these and similar losses have not been factored into the project cost,” said Brij Gopal, co-author of the 2016 environment ministry study and founder-coordinator of the Centre for Inland Waters in South Asia, a research organisation.

“Professor Gopal has made several representations to the environment ministry,” said Husain, the government spokesperson. “We have replied to all the issues and believe we have taken care of the environmentalist’s (sic) apprehensions.”

“We’ve been talking about inter-basin water transfers for 40 years,” environment minister Anil Madhav Dave told IndiaSpend. “Environmentalists and water resources experts have said a lot, the voice of local stakeholders has been least heard. We must ask their opinion too. With too many conflicting opinions, best is to implement one small link, assess the consequences over five to 10 years, and then decide further. I support balanced development. If we see adverse outcomes, we must stop talking about inter-basin transfers for good.”

The expensive outcomes of linking rivers: The lesson from Australia

Just as the Ken-Betwa project could adversely impact the ecosystem services of the Ken, other donor basins across India could suffer “significant losses of ecosystem goods and services as well as unacceptable social and economic impacts”, said the WWF-India’s Babu.

Environmentalists have predicted other possible adverse environmental outcomes of the proposed project—based on reason and/or global experiences—such as:

- Interlinking river basins could adversely impact the monsoon, V Rajamani, professor emeritus, Jawaharlal Nehru University, wrote in this 2006 comment in Current Science, an Indian scientific journal. If the water of India’s east-flowing rivers is diverted so that less water flows into the Bay of Bengal, it could set off a cascade of events—including low salinity, which keeps sea-surface temperature “high”, above 28 deg C and thus creates low-pressure areas—and intensifies the monsoon over much of the sub-continent.

- Damming India’s east-coast rivers to take their water westwards will curtail downstream flooding and thereby, the supply of sediment—a natural nutrient—destroying fragile coastal ecosystems and causing coastal and delta erosion, predicted the Mihir Shah committee report.

This observation recalls the failure of Australia’s Snowy River Scheme, a 145-km network of tunnels and 80 km of aqueducts transferring 1.1 cu km of water annually from the basin of the Snowy—a river flowing through mostly uninhabited mountainous region in eastern Australia into the Tasman Sea—to the basin of the Murray-Darling—an inland river developed for irrigation and water supply; construction began in 1949.

As the Snowy passed through one of the largest of its 16 dams, its flow was cut by 99%, as its water was sent to towns and villages downstream, a design that completely ignored—and ended up destroying—the river’s wetland habitat in its lower reaches, according to this 2007 WWF report.

Efforts to restore the flow of the Snowy have cost Rs 2,381 crore ($358 million), 57% of the project’s Rs 4,191 crore ($630 million) cost.

The design of India’s inter-river-basin water transfer project may also be flawed. “Given the topography of India and the way links are envisaged, they might totally bypass the core dryland areas of Central and Western India, which are located on elevations of 300+ metres above mean sea level,” said the Mihir Shah committee report.

Spain’s 286-km Tagus-Segura link and South Africa’s 200-km Vaal-Orange-Senqu link are other examples of global river-water-transfer projects that have run into trouble.

What might it cost, asked experts, to take apart India’s project, which is 262 times larger by value, if it similarly goes wrong?

“Instead of repeating the mistakes of other countries, India must learn from failed river basin interlinks,” said Shah, economist and former Planning Commission member, also co-founder of Samaj Pragati Sahayog (Social Progress Cooperative), an advocacy for livelihoods security.

Expanding agriculture—an aim of linking rivers—is possible through better irrigation practices

Expanding agriculture by making more water available to existing farmers and hitherto non-cultivated land are key aims of inter-river-basin water transfers globally and in India. However, global experience indicates that improving efficiency of irrigation could be a better way of making more water available.

India’s efficiency in using water is among the lowest in the world: 25% to 35%, against 40% to 45% in Malaysia and Morocco, and 50% to 60% in Israel, Japan, China and Taiwan, according to the Mihir Shah report.

“Focusing on improved irrigation practices would help achieve har khet ko pani (water to every field) at a far lower cost,” said Shah.

In Bundelkhand, for instance, efficient irrigation practices and localised water-saving solutions would yield immediate returns, something farmers there need help in implementing, said Gopal.

Before constructing more new dams, India also needs to better manage existing dams, on which Rs 400,000 crore ($60 billion) has been spent since 1947. “Bringing one additional hectare under irrigation would cost Rs 1.5 lakh by the improved management of dams and underground water as against Rs 5 lakh by constructing more dams,” said Shah.

Promoting water-efficient crops such as millets and pulses would also help expand agriculture. Instead, phase two of the Ken-Betwa link, with four dams in the upper reaches of the Betwa, mostly across Madhya Pradesh and UP, to better irrigate surrounding land and bring to the lower reaches of the Betwa water from the Ken is likely to “prompt a needless shift from pulses and millets to sugarcane and rice”, said Gopal.

Sugarcane and rice consume roughly six times and three-and-a-half times the water that millets and pulses need, IndiaSpend reported in August 2016. Millets are also far more nutritious than rice, we reported.

Why linking river basins would reduce groundwater recharge

India meets 80% of its water needs through groundwater, which also waters 60% of irrigated area. Close to 60% of the urban water supply and 85% of the rural water supply is groundwater, said Himanshu Thakkar, coordinator, South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People, an advocacy.

As a result, groundwater levels across India have plummeted and quality has deteriorated. In the decade ending in January 2016, water levels declined in 65% of the country’s wells, according to this 2016 Central Ground Water Board report.

“Inter-basin links would actually reduce groundwater recharge because forests would be destroyed, the river flow stopped and the local systems neglected,” said Thakkar. A better option would be to protect and enhance groundwater recharge systems and focus on community-driven groundwater regulation, said Thakkar.

Underground aquifers do not submerge land, displace people or reduce forests, and their water does not evaporate, as is inevitable with the river-basin interlinking project, said experts.

“Think of river basin interlinking only after exhausting the local potential for harvesting rain, recharging groundwater, watershed development, introducing better cropping patterns (non water-intensive crops) and methods (such as rice intensification), improving the soil moisture-holding capacity and saving and storing water,” said Thakkar. “We still haven’t done that.”

“We also believe in local solutions and watershed management,” said Husain, the government spokesman. “But this can happen side by side with other interventions, including inter-basin water transfers. Since India’s current dams are insufficient for its future needs, the earlier we make additional provision, the better, as resettlement and rehabilitation would become more challenging.”

(Bahri is a freelance writer and editor based in Mount Abu, Rajasthan.)

This article was first published on India Spend