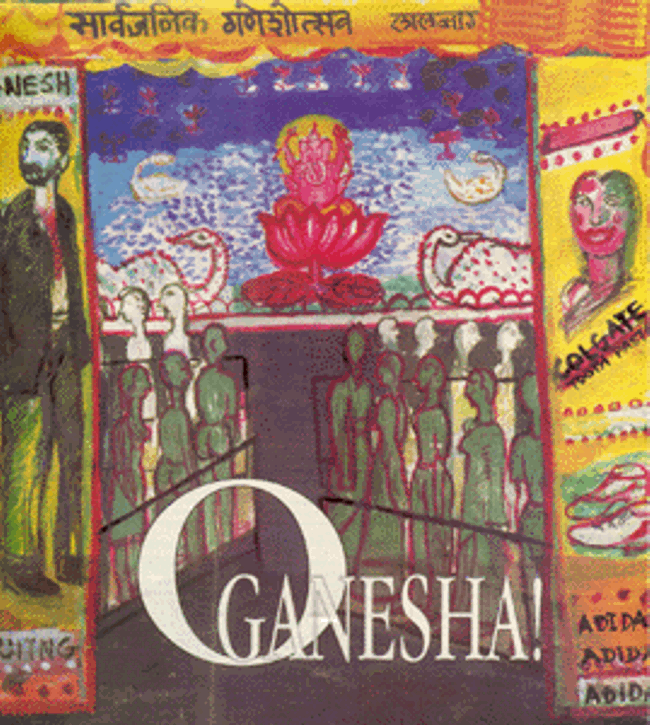

Communalism Combat published this two part cover story on the Ganesh festival in October 1996. We bring this to our readers during the ten day Ganesh festivities in Maharashtra, two decades later

We’ve always had a Ganapati at my mother’s place, started because my grandmother wanted it. For me as a youngster, the excitement was that of a social event stretched over 10 days… decorating the mandap, making chaklis and modaks for people who dropped in; the pooja who dropped in; the pooja part incidental.

Then, as a I grew older, observing the yearly ritual, I began to think how strange it was that though we bring Ganapati home for 10 days, and do all this around him we don’t actually look at Ganapati but the decorations, the dance we do around him, the food that is cooked, etc.

This thought in mind was confirmed when I visited other Ganapatis at Dadar and Lalbaug, the traditional areas. There were huge Ganapatis but the conversation point for people who visited was, apart from the size, centered around the film hoardings on display, the scale and extent of light and flower decorations and the surrounding mandap themes, whether it was a swan or army jawaans flanking Ganapati!

I found it exciting to explore this aspect through visits to various Ganapatis all over Bombay and actually experience how people feel about Ganapati and relate to this festival, especially in traditional areas where the celebrations are so important. Why do people throng there, visiting mandap after mandap all over the city?

After my exposure to Kalipooja in Calcutta some years later, with this experience of the Ganapati festival behind me, I realist that for these mad thronging crowds traveling all night, queuing up just to glimpse a deity or participate, all this wholesale participation was a source of recreation, to enable them to come out and be part of a massive community event, travel around at all hours, something that they would otherwise never do.

This festival extended from being a religious or social event to a cultural occasion: plays were staged, films shown, beautiful music performances heard and competitions held. Theatre activities were also held. All these were opportunities for local talent – not necessarily great actors or actresses – to come forward and display their talent before a community audience.

Artists and stage decorators found an occasion to contribute their talent: brilliant ideas of local technology are innovatively applied in stage decoration, in lighting. The way lights and colours are used are perhaps very gaudy but fascinatingly worthy of study.

Have you noticed the themes that emerge from Ganapati mandaps?

They are often social or political and are an interesting expression through popular art. Every time we’ve had wars, the Indo-China war, (1965), the Indo-Pak war (1975) all the Ganapati mandaps in those years sat (or stood) with a background of the Himalayas – and though Ganapati was spared – jawaans engaged in scenes of combat stood around while Nehruji also figured. Even here, the Ganapati though central was small, incidental.

In the eighties, the Shiv Sena and the BJP systematically appropriated this, an occasion which reflected the popular expression of ordinary people to further their ideology and to brainwash people: the SS-controlled mandaps which portray the Marathas (pitted against the Moghuls) and those of the BJP, which show dominant images of Ram and Sita, serve their respective ideologies well.

These, and some other aspects that have emerged in recent years I find very disturbing. The long queues outside the Siddhivinayaka (another “avatar” of Ganesh) temple round the year when people seek a divine boon or blessing, for example, have nothing to do with this celebratory cultural event which also has its positive sides. That is just plain andhashradha (blind faith) linked closely with a general growth in religious consciousness. That is, for me, upsetting.

We all know that the Ganapati festival as we see it in its sarvajanik (community) from, particularly the aspect of its public immersion preceded by a huge procession, was started by Lokmanya Tilak as a way of mobilising people against the British, (leave aside the fact that it was also conceived or perceived in competition with the moharram procession), but today this same politicization has taken a distinctly communal turn.

The ten days of Ganapati celebration are used by certain parties who have taken control of all the Ganesh mandaps in the city, to brainwash people… they use theatre, skits, plays and films, songs to further their agenda. And because it is a Hindu festival, in Maharashtra it is obviously the Shiv Sena and the BJP who are the pudharis (the leaders). And, when we say they use the festival to further their agenda, don’t we know how dangerous that agenda is?

During the communal riots in Bombay in 1992-93, the mahaartis were used to mobilize ostensibly against Muslim namaazis. Even now, this tension is still there just below the surface, people are trying too cope with it individually but these parties don’t want to allow people to forget and are actively creating further tensions.

| Ganesh, greenbucks …. More than 9,000 mandals in Bombay are engaged in local organizing and celebrations according to official figures. For Maharashtra, the figure in 35,000. In an interview given to The Times of India the president of the Brihanmumbai Sarvajanik Ganeshotsav Samiti’s co-ordination committee, Arun Chaphekar gave total figures, staggering in their entirety, of money collections made on occasion of the 10-day long annual festival. He said that all the mandals together collect around Rs.25 crores from the people. Besides this, the collections from banners, advertisements and donations is approximately Rs. 125 crores. According to Chaphekar, there are five Ganapati mandals that have a budget of Rs. 25 lakhs each, about 100 mandals spend close to Rs. 10 lakhs each. In his opinion, the big mandals spend 20 per cent for the decoration, 10 per cent for lighting and 5 per cent for the idol. The rest, is spent on cultural programmes. Explaining that immense business is also generated during the period, Chaphekar claim also was that the authorities impose hefty taxes on some of the items used for the pooja like the janvi (sacred thread), fruits, coconut and beetle leaves. Whatever money remains from the annual collections, is put aside into fixed deposits for the mandal’s future functions. All in all a huge some of money is handled by mandals and in this age of political non-absolutes, when political parties dominate the sarvajanik Ganeshotsav scene, a possible case can be made for scrutiny: funds collected in the name of the Lord should surely not grease political palms? …and the de-greening of Bombay The Bombay High Court ruling that limited loudspeakers around the Ganapati mandals to 11.30 p.m. afforded a measure of victory to the green lobby that has been attempting to raise consciousness and impose regulation at the high noise-levels generated during the 10-day celebrations that far exceed the permitted decibel limits under the Environment Protection Act, 1986. “The EPA does not permit noises above 45 decibles at night in residential areas, but loudspeaker noises are within the 80 to 100 decible range,” pointed out Y. T. Oke from the anti-noise pollution committee. The petition was filed jointly by this organization with the Bombay Environment Action Group (BEAG) and the Association of Medical Consultants (AMC). While Chaphekar of the Ganeshotsav samiti reacted by asking why the green lobby was focusing on religious festivals when other sources of noise pollution, including that generated by vehicular traffic, was not sought to be controlled, Oke clarified that it was not any particular festival that was the “target” – last year, similar legal action was sought to be taken at the time of the Navratri festival (nine days of dancing the raas-garba culminating in Dussehra) but by the time they attempted to do so, loudspeaker licenses had already been granted. (If these were the figures in 1996, what would they be now? |

Then the money aspect, crude commercialization, has also crept in Ganapati has become a front for huge money collection (see box). So not only does the political brainwashing go on, there are select political parties behind the festival Bombay who are in complete control of all the mandaps, and they will use it, each year, as a front to collect funds for the next elections.

Do you remember the “Vardhadada’s” Ganapati at Matunga? A criminal and a don who sought social respectability began to be seen as a Robin Hood figure through this massive Ganapati that he instituted, replete with lavish lights and decorations. It was the trend started by Vardha, after which all these other “sponsored” Ganapatis started. The local political heavweight of simply a deity sponsored by Gwalior or Dinesh suitings!

The whole charm of a community event, the original sarvajanik Ganapati festival, made possible through painstaking collections of small and voluntary individual contributions, is gone. The element of faith and worship, individual and collective, has been replaced by the crudeness of a purely commercial activity.

How many people actually think of poor Ganapati? The fact that he is such a cute God, as an art form, the Ashtavinayaka, he is beautiful. As an artist I call him cute, children take to him, he eats ladoos and modaks, he’s half-elephant, half-human, he has a perculiar vahaan (vehicle of transport, the rat): everything to awaken the curious. And the endless chain of Ganapati stories on which so many children have fantasised.

Where has the Ganapati got lost in all this?

(As told to Communalism Combat; Shakuntala Kulkarni is a well-known artist)

Also Read

O GANESHA! – Part 2