Excerpts from section on primary and secondary education, forming part of the chapter “The Indian education system”, in the policy brief titled “Demographic Dividend or Demographic Burden? India’s Education Challenge” by Christophe Jaffrelot and Sanskruthi Kalyankar, published by Institut Montaigne, an independent think tank based in France:

One of the key indicators that the government of India is not updating any more is the dropout rate. The last official report providing information on that front uses figures released for the year 2015- 2016. It showed that the Right to Education Act, passed in 2009, had resulted in a massive reduction of the dropout rate (to a meagre 4%) for the Elementary classes (from classes 1 to 8) because the RTE Act made education compulsory till class 8. The rate, afterwards, jumped to 17% in classes 9 and 10.

In 2018, in response to a question asked in the upper house of the Indian parliament, the Rajya Sabha, the Minister of State for Human Resources Development, Upendra Kushwaha, informed the assembly that this rate, still for 2015-2016, was 16.88% for girls and 17.21% for boys18. These figures are consistent with the Gross Enrollment Ratio (GER), which is the number of individuals who are actually enrolled in a particular level of education per the number of children corresponding to this enrolment age.

In 2015-16, this ratio had reached 97% for the Elementary classes, but had dropped to 80% for the Secondary classes (9 and 10) and was only of 56.2% for the Senior Secondary classes (11 and 12). These national averages need to be disaggregated statewise. For the classes forming the “Upper Secondary” level the figures are much lower in some states of the Indian Union: 46% in Madhya Pradesh, 43% in Gujarat, 40% in Karnataka, 36% in Bihar etc.

While the GER has significantly increased so far as the elementary schools are concerned, the quality of the education that is offered there remains debatable. It is not easy to measure comparatively since India dropped out of the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) in 2009 after being placed 72nd out of 74 nations (including Brazil, China, Thailand, Indonesia, Viet Nam etc.). India then claimed that the program was not sufficiently adapted to the Indian context.

In order to assess the students’ skills, the Government of India created its own National Achievement Survey in 2012 which analyzed first the learning capacity of Class 8 students. It showed that 29% of the students “struggled in questions that required reasoning”, and that 33% of them “struggled with questions that required application and reasoning”.

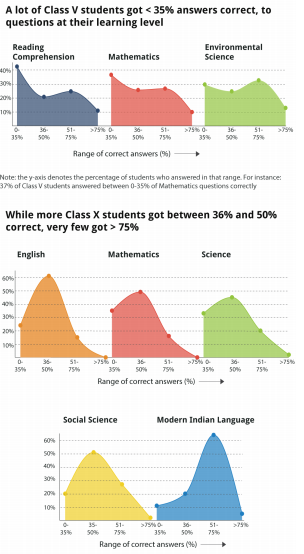

After taking over in 2014, the Modi government organized a similar exercise that covered about 2.5 million children of Classes 3, 5 and 10 in the framework of the National Achievement Survey. Over a quarter of all the Class 5 students scored between zero and 35 out of 100 in reading, mathematics and environmental science.

Primary and secondary education being state subjects, some state governments have initiated policies that have resulted in significant improvement, as evident from the uneven literacy rate that one finds across the country. Delhi is a case in point, but there are other, older and more convincing success stories, including those of Kerala and Himachal Pradesh.

These findings have been reconfirmed by other surveys, including the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER), which has been published in 2018 by the NGO Pratham. This remarkably comprehensive exercise – 546,527 children have been surveyed in 2018 – which is repeated every year in rural India since 2008, shows that their skills remain lower than what it was at the elementary level in 2008 from two points of view.

First the proportion of the children in government schools in Standard 5 who can read Standard 2 level text has declined from 53.1% to 44.2% and those who can do a simple division has diminished from 34.4% to 21.1%. These figures are not easy to interpret. The decline may be due to the Right to Education Act (2009) that has suddenly resulted in the enrollment of children from the poor families that till then did not send their children to school and had a very low intellectual capital.

Indeed, the percentages mentioned above dropped by nine percentage points between 2010 and 2012 while the GER increased; but they are going up again, as if schooling started to compensate the low intellectual capital of the new comers. Registration is one thing, but attendance is another.

The Annual Status of Education Reports show that there is hardly any improvement on that front. Since 2010, the proportion of children attending schools in classes 1 to 8 oscillates between 71 and 72%. One of the reasons for this stagnating, rather low level of attendance pertains to the available facilities. In spite of the strict conditions under which a government school can be registered since the passing of the RTE Act (2009), all the schools don’t have usable toilets – 74.2% of the rural schools visited by Pratham had one – or separate toilets for girls (66.4% had some), electricity connection (75% had one) or did not give miday meals (91% did). The situation of higher education is better, but is naturally affected by that of the secondary education.

The case of Delhi

In this state, the government of Arvind Kejriwal, whose party – the Aam Aadmi Party (the Party of the Common Man) – took over power in 2015 has given a priority to education, and a new kind of education. The education budget increased by 106% from 2015-16 to 2016-201724, so much that in 2017-18, it represented 26% of the state’s budget. This money was used to build 25 new schools and 8,000 classrooms in three years.

But improvement was not only quantitative. Under the influence of educationists, including Atishi Marlena, who worked as adviser to Education Minister Manish Sisodia, the Delhi government has focused on the foundation of students from grades 6th to 8th who could not even read a simple passage or solve a math problem. A basic learning material/reading assessment tool for the campaign was developed by the Pratham and helped to close the gaps of those who lagged behind.

The Delhi government also promoted “arts in education by nurturing and showcasing the artistic talent of school students at the secondary stage in the country through music, theatre, dance, visual arts and crafts”. In the same spirit, students between Class nursery and Class 8 have a 45-minutes ‘happiness period’ which includes “meditation, storytelling, question and answer sessions, value education and mental exercises”.

The Delhi government has invested a lot in the training of teachers, who have been sent abroad in order to learn from international experiences and who have benefited from an Online Capacity Building Programme (OCBP). In order to explain these innovations to the parents and to improve the communication with the teachers and the parents, the Delhi government “instituted a Mega Parent-Teacher Meeting Scheme, and strengthened and regularized the School Management Committees” where parents were represented.

Last but not least, the government has established 11 incubation Centres giving them a grant of Rs. 15 million for each: “College/university students with creative minds are given an opportunity to explore their ideas through a platform and financial assistance”. These innovations bore fruits, as evident from the results of the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) examination for Class 12.

The pass percentage of Delhi government schools increased from 88.36 per cent in 2017 to 90.68 per cent in 2018, even as private schools of the city lagged behind at 88.35.The overall performance of Delhi government schools was the second best in the country, after Thiruvananthapuram (Kerala)”.

However, these results are contested by other reports, including the one that the Praja Foundation, an NGO specializing in education submitted in 2019.

- First huge vacancies remain (25% as of the latest U-DISE figures).

- Second the Delhi government continues hiring contract teachers (20% of the total, even though RTE expressly bans the practice).

- Third, it has installed cc-TV cameras in classrooms to monitor teachers to increase “accountability”, but this move has been counterproductive.

- Fourth, the teacher trainings held in foreign locales have not translated to much use in local classrooms for obvious reasons.

Download full policy brief HERE

Courtesy: https://counterview.org/