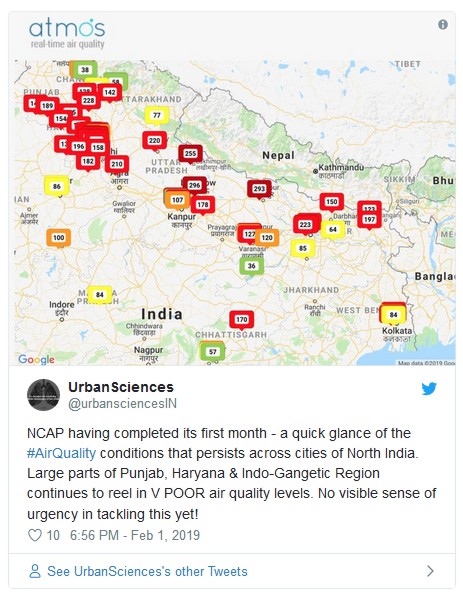

New Delhi: Almost a month after the launch of a national programme for air pollution abatement, cities across India–home to 14 of the most polluted cities in the world–continued to breathe toxic air during the winter of 2018-19.

Only Patiala among 74 cities assessed by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) met the national safe air standards as on February 4, 2019, said a CPCB daily bulletin.

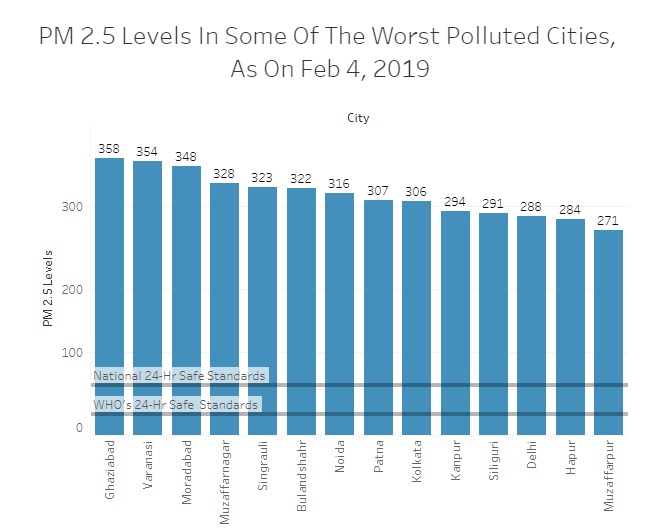

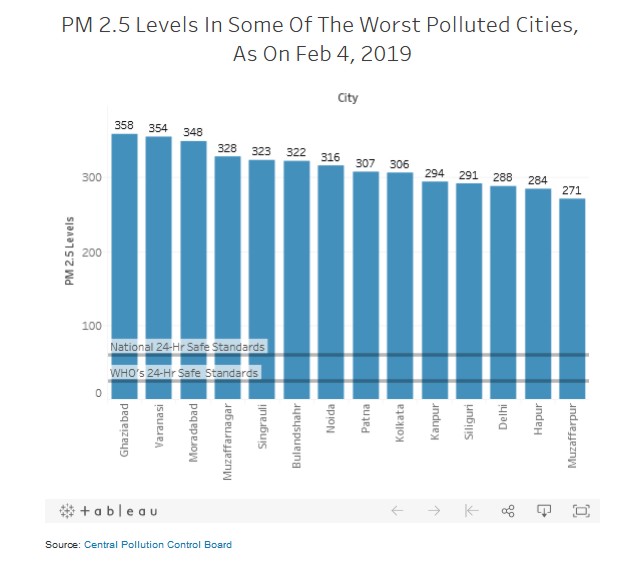

On January 17, 2019, Ghaziabad, an industrial city bordering capital Delhi, reported a 24-hour average for toxic particulate matter (PM) 2.5 that was 14 times higher than World Health Organization’s (WHO) safe standard. The PM 2.5 average that day in Ghaziabad was six times higher than even India’s own, more lenient, safe-air standard. The national standard allows 2.4 times higher levels of particulate matter than the WHO’s.

The air quality in the world’s most polluted city, Delhi–home to 20 million people–remained above safe limits almost all days this winter between November 2018 and the first week of January 2019, IndiaSpend reported on January 17, 2019.

To fix this pollution crisis, the Indian government launched its first-ever national framework called National Clean Air Programme (NCAP) on January 10, 2019.

With a budget of Rs 300 crore for financial years 2018-19 and 2019-20–about Rs 2.9 crore per city–the programme will focus on 102 polluted Indian cities. The plan is to bring the country’s overall annual pollution levels down by 20-30% over the next five years to 2024. The plan counts 2017 as the base year.

The programme that envisages a national source inventory for air pollution will issue guidelines for indoor air pollution, expand air quality monitoring network in cities and in villages and conduct air pollution health impact studies.

NCAP, however, is a flawed plan as we explain later, because it lacks legal mandate, does not have clear timelines for its action plan and does not fix accountability for failure.

India saw 1.24 million deaths in 2017 due to polluted air, IndiaSpend reportedon December 7, 2018.

Source: Central Pollution Control Board

Targets are not ambitious enough to make a significant difference

Twenty-eight of India’s 74 cities (about 38%) assessed on February 4, 2019, by the CPCB struggled to breathe that day. Cities such as Lucknow, Varanasi, Ujjain, Patna, Delhi, Kolkata, and Singrauli recorded ‘poor’ and ‘very poor’ air quality.

Another 35 cities, including Jaipur, Kalburgi, Jalandhar, Mumbai and Pune, suffered ‘moderately’ polluted air.

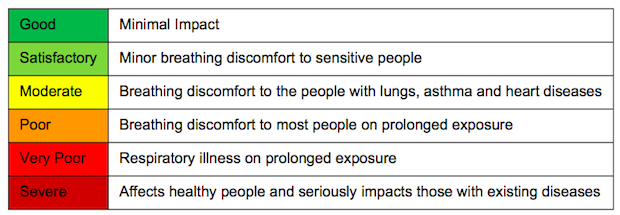

While moderately polluted air could cause breathing discomfort to those who have asthma, lung or heart diseases, severely polluted air make even healthy people ill.

Possible Health Impacts Of Polluted Air

Source: Central Pollution Control Board

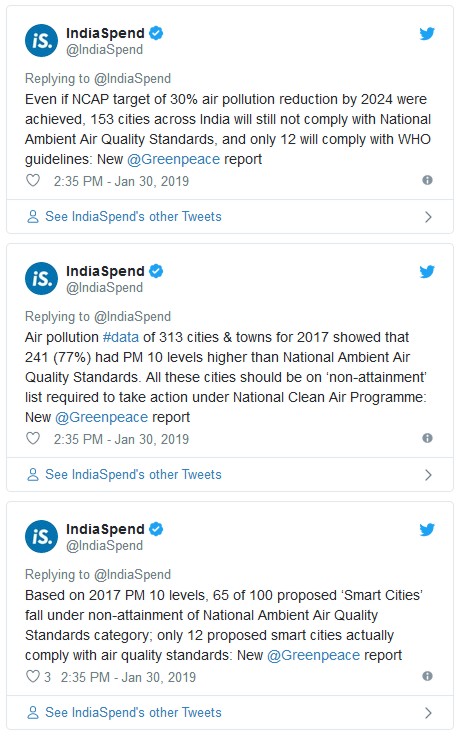

Most of these cities, under the NCAP, are expected to create their own plans to curb air pollution over the next five years. No city-level targets were announced in the NCAP. But even if the cities were to reduce their pollution levels by the national target of 20-30%, they will still not be breathing safe air.

Take for example the 14 cities that make it to the global worst list. Even after we make reductions in tune with the NCAP’s national targets, none of them will meet national standards for PM 2.5 by 2024.

Source: Annual Averages For 2017: World Health Organization, Annual Averages in 2024: Reporter’s Calculations

Even after the targeted pollution cuts, the PM 2.5 levels in these 14 cities is likely to range 7-12 times over the WHO safe limit and 2-3 times over the national safe limit.

The NCAP agenda: How it will work

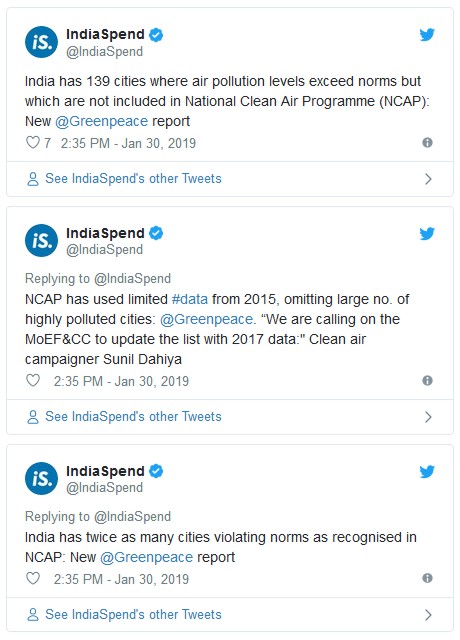

The NCAP is described as an evolving “dynamic” five-year action plan that may be further extended after a mid-term review in 2024, as per the government release. It will be implemented in the 102 cities that did not meet the annual national standards of clean air over five years to 2015. These criteria, however, do not include more than 130 polluted cities.

The programme, guided by the ministry of environment, will be implemented with the help of other ministries, such as road transport and highways, petroleum and natural gas, renewable energy, heavy industry, housing and urban affairs, agriculture and health.

Mitigation actions proposed involve plantation drives in highly polluted areas, management of road dust, power sector compliance to stringent pollution guidelines and curbs on stubble burning.

“The good thing is that it is quite comprehensive in a way that it is looking at India as a whole and not just as Delhi-NCR which has been the case very often for pollution related conversation,” Hem Dholakia, senior research associate, Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), a Delhi-based think-tank, told IndiaSpend. Certification of monitoring systems and installation of pollution forecast systems were also good ideas introduced in NCAP, he added.

But the national ambient air quality standards need to be reviewed to declare standards for other pollutants, including finer particles than PM 2.5, Dholakia suggested. “As we bring in measures to control pollution, the nature of pollutants, their composition and contribution changes,” he said.

Air quality tests done in November and December 2018 in Delhi and Gurugram showed dangerous levels of heavy metals such as manganese, nickel and lead in the air. Of these, India does not even have standards in place for manganese.

A plan without timeline or teeth

Unlike the draft made public in July 2018, the final NCAP has a national target of 20-30% pollution reduction. But experts have found it lacking in critical areas.

Post-NCAP, the environment ministry is unlikely to announce any large-scale air pollution reduction effort for a couple of years. In this scenario, NCAP should have signaled some major sectoral changes and listed clear timelines, said Santosh Harish, fellow, Center for Policy Research (CPR), a Delhi-based think-tank.

“NCAP should have had clarity around the actions, targets and timelines for sectors like transport, power and construction,” Dholakia said. A clear matrix to monitor the programme is essential to check its efficacy, he added.

“Unless there are clear targets to follow, how can regulating bodies find teeth to ensure pollution reductions?” Sunil Dahiya, senior campaigner, Greenpeace India, a non-profit, told IndiaSpend. “It is needed even more because NCAP has no legal binding over states–it is just a central scheme.”

NCAP talks about “stringent enforcement”. But one of the major reasons why State Pollution Control Boards (SPCBs) fail to enforce laws is because existing environmental regulations do not provide them with enough teeth or flexibility to act, Harish said.

“So one of the things that NCAP could have laid out, given that it recognises governance as a problem, is some kind of a commitment towards reforming the regulatory structures [under Air Act and Environment Protection Act],” he suggested.

Why Delhi’s pollution control strategy failed

Currently, the national capital Delhi is the only city in the entire country with an active long-term Comprehensive Action Plan (CAP) for air pollution control and an emergency response plan, the Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP).

CAP measures include traffic management, use of cleaner fuels and increased electrification of vehicles. GRAP, on the other hand, kicks in when pollution in the city crosses hazardous levels and includes emergency measures to cut pollution–ban on garbage burning and entry of trucks into the city and the closure of power plants, brick kilns and stone crushers.

GRAP failed because 12 responsible agencies including the transport department, the ministry of environment, the Delhi Metro Rail Corporation which operates across the NCR and neighbouring states could not work together. At GRAP meetings, the attendance of the responsible agencies was as low at 39%, IndiaSpend reported on January 18, 2019.

There is high risk that other cities will end up with pollution plans modelled around Delhi’s CAP. This template is flawed because it has a laundry list of more than 90 action points with loose timelines.

NCAP’s city-specific plans could have been more effective if they use the information gleaned from Delhi. Source apportionment studies conducted for Delhi, for instance, are readily available as a template for other cities. So NCAP could simply have suggested specific pollution reduction targets for sources, such as transport and industries, with clear timelines, said Dahiya.

NCAP also mentions regional and transboundary action plans but provides no clarity about what will be done. It would have been really helpful to see an airshed management plan being explicitly mentioned in the NCAP, said Harish. Airshed management combats pollution in a geographical area where local topography and meteorology limit the dispersion of pollutants.

In the absence of an airshed management plan “…cities may make plan to tackle pollution but they may not have the wherewithal to deliver on those actions given that many sources may fall outside of their purview”, said Dholakia.

Some of the plans submitted by cities and accessed by Greenpeace are only limited to municipality boundaries, and they talk about only transport management and road and flyover construction. It is very important for cities to stretch their neck and look out of their peripheries to deal with sources–like industrial clusters, brick kilns, power plants located just outside their jurisdiction–while figuring out their action points to tackle air pollution, said Dahiya.

No concrete action for rural India

About 75% of 1.09 million deaths in India in 2015 attributable to air pollution were in rural areas, IndiaSpend reported on January 18, 2018.

In NCAP, the government talked about monitoring air quality in rural areas for the first time, said Dholakia. But the plan says nothing further about mitigation strategy which is disappointing, said Dahiya.

Finances could be a problem area for NCAP too: Its proposed cost is about Rs 638 crore over the next five years. But CEEW’s research found that to clean the country’s air to meet just the national standards, about 1.1 to 1.5% of India’s annual gross domestic product will be needed, said Dholakia.

“It is dynamic document,” said Dahiya. “I hope these things are fixed as the plan evolves.”

(Tripathi is a principal correspondent with IndiaSpend.)

Courtesy: India Spend