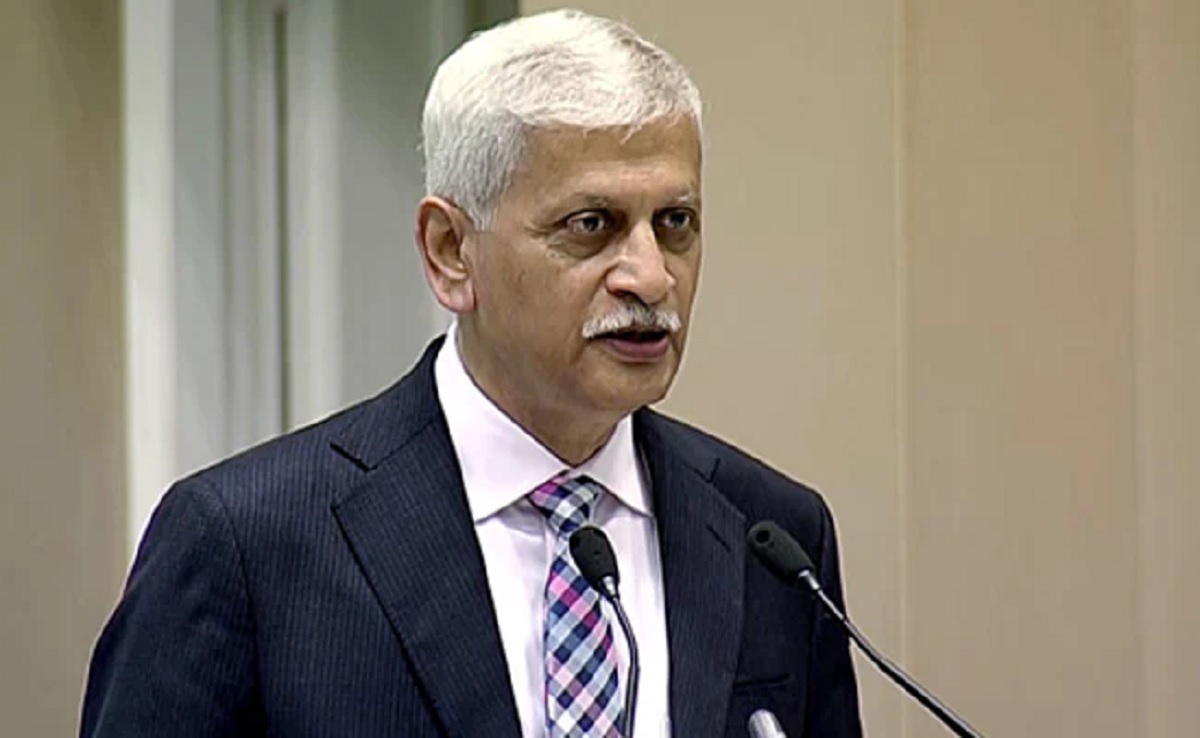

Former Chief Justice of India UU Lalit expressed serious concern over the perpetual and indiscriminate invocation of Section 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure by the Delhi police in the national capital. This provision confers vast and indiscriminate powers on magistrates, and in the case of a commissionerate like Delhi, on the police chiefs, to issue urgent, preventive directions, including orders prohibiting large gatherings, in anticipation of an escalation of hostility or any other emergent situation. Justice Lalit said:

“Section 144 confers emergency powers. The purpose of invoking it may be laudable, but where it is invoked in this fashion, it indicates the means to the end do not matter at all because the end itself is thought to be of such sterling quality. To condone this would be to confer on executives, who may be police officers, drastic powers. This kind of power in a country governed by rule of law and democracy is not acceptable.”

The Delhi police comes under the union of India’s ministry of home affairs (MHA).

The former CJI, Lalit was speaking on Saturday at a launch of areport titled ‘The Use and Misuse of Section 144 CrPC: An Empirical Analysis of all the Orders Passed in 2021 in Delhi’ by a group of Delhi-based advocates comprising Vrinda Bhandari, AbhinavSekhri, Natasha Maheshwari, and Madhav Aggarwal. The report establishes that emergency powers under Section 144 were exercised by the Delhi police as many as 6,100 times in 2021. Also in attendance at the event was senior advocate Rebecca John.

Terming the report an ‘eye-opener’, Justice Lalit said while the ‘regular’ logic for issuing such prohibitory orders or the ‘regular’ areas in which they are supposed to be exercised were justified, such a power could not be utilised for a purpose not envisioned by the law. When asked about the imposition of Section 144 to curb protests and dharnas, Justice Lalit said,

“Participating in peaceful protests is your constitutional right. No one can deny that.” However, he accepted that the police had reasons to be ‘extra vigilant’ during protests to prevent an escalation of violence. He said that the imposition of Section 144 during the pandemic to ensure social distancing was also justified in view of the urgent need to prevent the virus from spreading. “One can understand these. But how can normal business ventures be sought to be curtailed or to be regulated through the modality of Section 144?” The report reveals that the Delhi police issued orders under Section 144 for a slew of reasons apart from curbing threats to public order, including installation of CCTV cameras, regulation of businesses and services through record and registration requirements, regulation of courier services, prohibition of consumption of tobacco in hookah parlours, etc. “If you want, for instance, to have CCTV cameras in various places, including ATMs, Section 144 certainly is not the fulcrum or the foundation on which you can build this edifice,” Justice Lalit added.

“The power must be exercised in a manner known to the law, by the competent authority, and for the intent and purpose for which it was conferred,” Justice Lalit firmly said. While Section 144 directions could be challenged, litigation was time-consuming and expensive, the former judge pointed out. “It is not as if these orders pinched the shoe at every juncture compelling people to move the court, but rather posed a potential threat for prosecution, which could result in imprisonment for up to two years.” He added, “This is the kind of threat to which they are vulnerable. There is a sword hanging over their head.”

Finally, Justice Lalitopined that the report be placed before lawmakers or before a court of law. While the validity of the legislation had already been upheld in BabulalParate(1959)and MadhuLimaye(1970), the mechanism of public interest litigation, he suggested, could be employed to point out to a court of law that the premise on which the legislation was held to be valid is “being played around with”. It may be highlighted that the provision is being used for purposes not envisioned when it was enacted or subsequently, upheld, Justice Lalit said, “If someone were to take this matter to the court, I think some solace could be secured.”

The detailed speech and event was reported in LiveLaw.

Related:

Free legal aid does not mean poor legal aid: Justice UU Lalit